Emily Dickinson’s ‘Gorgeous Nothings’ shows the poet’s hand

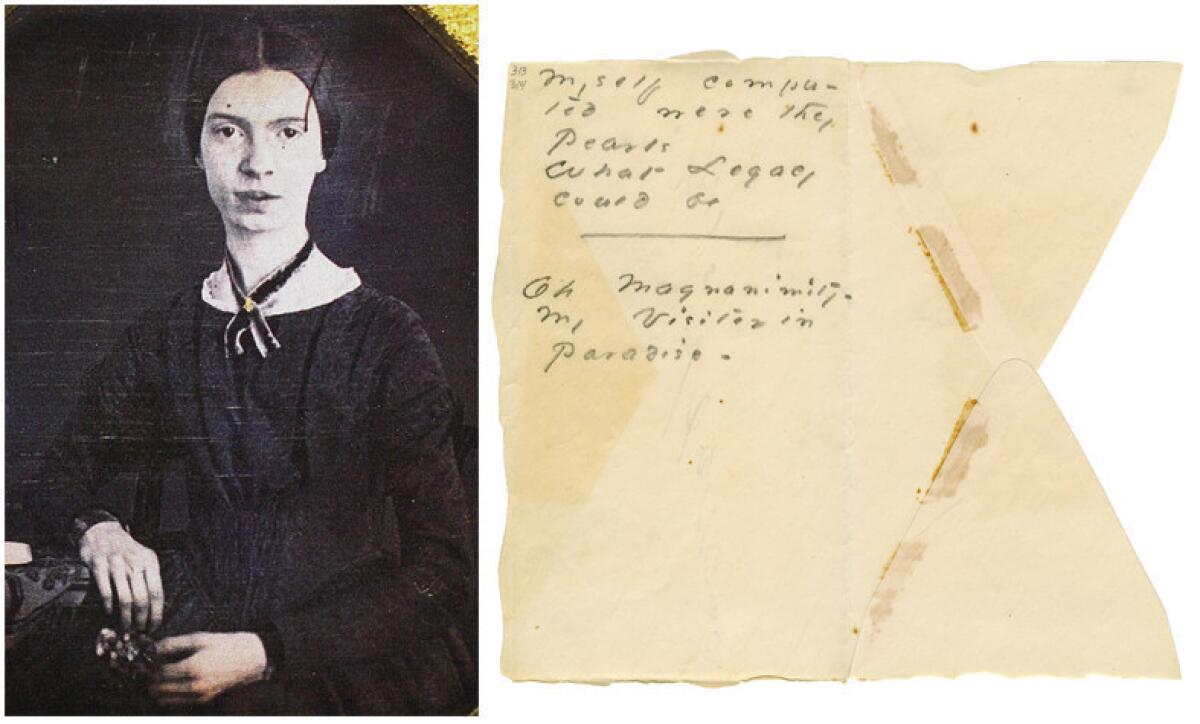

In 2012, a daguerreotype surfaced that was thought to be of a midlife Emily Dickinson, causing an Internet frenzy. As far as we (the frenzied) knew, there was only one known photographic image of the poet. That 1847 picture, taken when she was 16, is enigmatic, extraordinary and a little unsatisfying. Her single expression is dual: both deep and blank, both innocent and knowing. Dickinson readers recognize this intoxicating, paradoxical doubleness well: It is so very Emily. What wouldn’t we give for more of her? Just one more glimpse?

Perhaps we’d contented ourselves with that single image, but suddenly there was a chance that we could behold her mature face. We squinted and cocked our heads, trying hard to divine whether this woman in the “new” photo was truly Our Emily. I thought, reluctantly, that it wasn’t. But now that the possibility had been presented, I was eager for another view, another angle of her.

The stunning art book “The Gorgeous Nothings” offers us this view — slant, as Emily liked things. In 52 color reproductions of the writings on envelopes, we still never see her face. But she shows us her hand.

Sign up for our email newsletter, “Bookshelf”

The synecdochal “hand” makes sense: Dickinson’s form was fragments. So the words and images collected here aren’t of drastically different order than her poems. Many of these scraps — drafts — became poems, some altered, some unchanged. Readers might recognize “Unknown — for all/the times we met — / Estranged, however/ intimate — /What a dissembling/ Friend —” and delight to see that this draft includes an extra couplet, dropped in the final version. (For those who miss these subtleties, full annotations are included.)

Those mysterious poems — in which an excess of dashes seems to represent omitted trajectories of vast and unwordable glory — say more about human consciousness and concerns in their few lines than we can understand in one read. We re-read Dickinson. We study her. We sometimes act as if we’re reading runes or translating an ancient alien text: What could she possibly mean? What Emily Dickinson meant matters to us, because hers is the kind of poetry that helps us live our lives: “after great pain, a formal feeling comes.” Yes, it does, one might say after the somewhat comforting conventions of a funeral or a memorial service.

What Dickinson means now seems almost the opposite of what she used to mean. She was often described/read as virginal, a prude. Now we eroticize her, reading into her poetry strong sexual desire and lust (see her poem “Wild Nights —” and Billy Collins’ “Undressing Emily Dickinson”). We look at the letters in which she humbly requests her would-be mentor to give her poetic guidance, and we see a powerfully in-charge, audacious, ambitious and seductive woman posing as a supplicant. Dickinson didn’t need artistic guidance, and she knew it, we now see.

She was once noted for writing tiny fascicles, writing tiny poems, though her contribution to American letters is now distinctly giant. As artist and author Jen Bervin says in her beautiful introduction to this book, the poet is “petite by physical standards, but vast by all others.”

“The Gorgeous Nothings” shows us another side of this magnificent artist’s doubleness. For most of us, our scant and vague scribblings truly are nothing, and we throw our old envelopes in the recycling bin. Emily Dickinson apparently slit open received envelopes to use the blank insides to write on; her scribblings, the jottings of this genius of ear and eye and hand, transform into art. This book shows the fronts and backs of each envelope and where possible aligns them so we can sense as closely as possible what the double-sided original object must be like. Also, the scribblings are “translated” or typeset on the facing page, with cross-outs and dashes, creases and all.

A large circle of archivists, curators, scholars and librarians helped Marta Werner and Jen Bervin in what is clearly a complex project and a labor of love years in the making. The impressive graphic design and ingenious typesetting make this more of an art book than a poetry book, the ultimate presentation by library or archival standards rather than a collection of fragments. But the star of the show is the handwriting.

It’s revelatory to see the hand script: the pressure of the pencil, the moment of pause that allows the line to waver a bit, sometimes light and near-invisible, sometimes bold and certain. This is surely one of the geekier things to delight in, that here we get a chance to encounter Dickinson not in her art but in her artlessness. (Normally, when we visit Emily, she is properly attired to receive guests. Never have we been received by Dickinson in her dressing gown.) When we look at the handwriting we see the hand, her hand, and we see a different part of her mind and heart. We see Emily Dickinson the Poet not as she is writing poetry but as she lives and thinks and mutters to herself.

It turns out that the way she lived and thought and muttered was always already poetry. On a tiny triangle of paper she wrote, “One note from/one Bird/is better than/a million words/A scabbard/ has — holds /but one/sword.” And her formal choices become clear: She ran out of room. She composed the poem so it would fit the scrap. She ended it where it ended because she ran out of paper. That fragment was her form. That form was its function.

Many of us who love Dickinson love her for both what she says and for what she doesn’t say; that is, we love her not just for her silvered and slippery words but also for her ellipses and her gaps and her long silences between words in which we glean what we ourselves might actually feel. We often feel we are reading ourselves when we read Dickinson; we feel we are collaborating in the creation of her poems. Making them our own, as it were. We find our own context where she is vague, making it fit us. We wrap our experiences around her specific images, fitting her again that way too.

We see from “The Gorgeous Nothings” the way her art and life were not separate endeavors. Dickinson wrote poetry every time she addressed or received an envelope. Whenever there was paper around, she put quill or pencil right to it. Dickinson, master of paradox. started these un-conversations with nobody, and so many years after her death, now — in curled script, with their sweet, perfect Ms and half-formed Ys, unpublished and unseen until now — they speak to us. And they have so much yet to say. It’s Emily Dickinson. We’re listening.

Shaughnessy is the author of several poetry collections, most recently “Our Andromeda.”

The Gorgeous Nothings

Emily Dickinson, edited by Marta Werner and Jen Bervin

Christine Burgin/New Directions: 255 pp., $39.95

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.