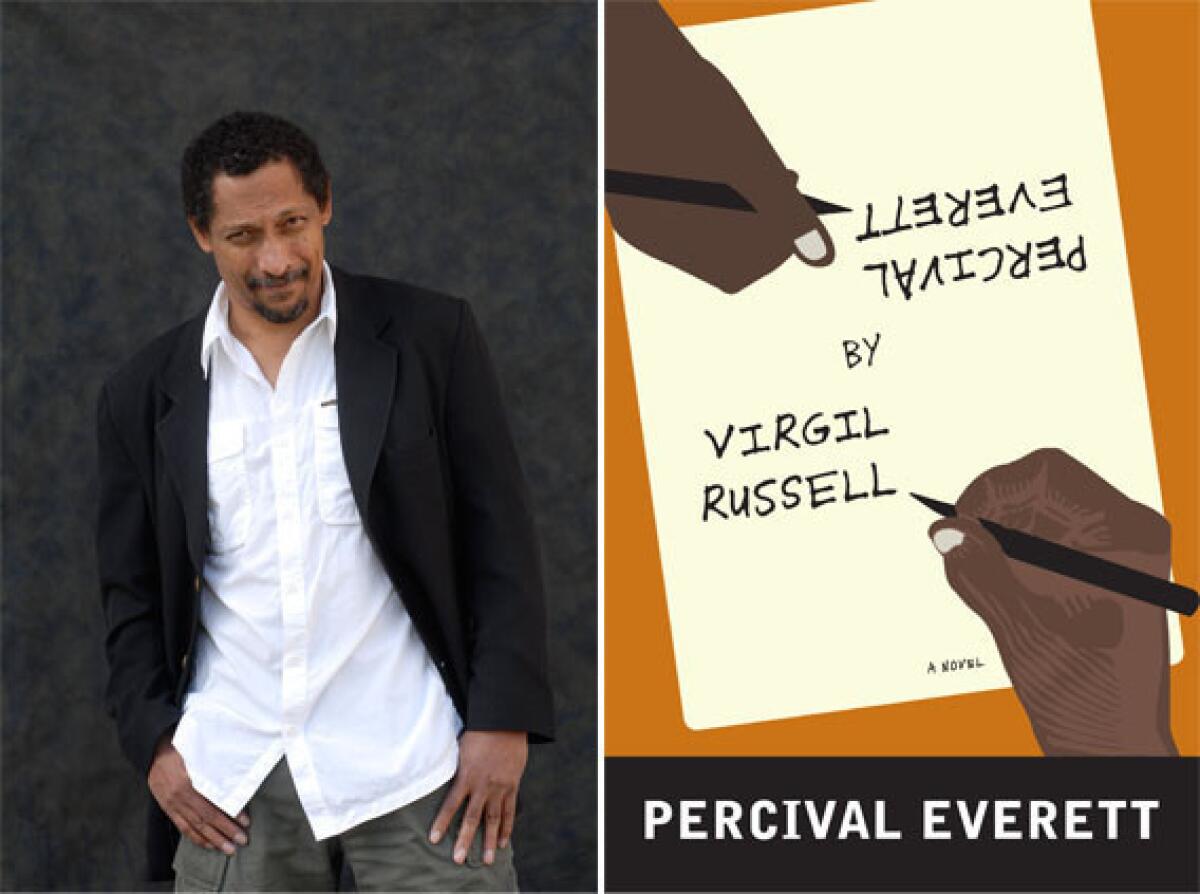

Meet Percival Everett and ‘Percival Everett’

Percival Everett by Virgil Russell

A Novel

By Percival Everett

Graywolf Press, 227 pp., $15 paper

When I read Percival Everett’s new book, “Percival Everett by Virgil Russell” — or Percival Everett read me his new book, even though he wasn’t there, of course, you don’t get a physical human with a book, most times; still, in a sense he read me his book — I found that I liked not only the book but also Percival Everett.

He wasn’t there at all, that interesting professor and novelist, that attractive, often humorous, middle-aged black literary stylist who lives and writes in Southern California, experimenting with the structure and conventions of fiction. I liked him anyway.

I’ve never met Percival Everett; yet it’s fair to say that, having read “Percival Everett,” I now know him better than I know many of the people I have met, whose bodies have inhabited the same rooms mine has, concurrently. And though the matter of character likability is irrelevant to me as a reader, the matter of tone likability — arguably even of authorial likability — is not. Which is why I mention that I took the liberty of liking, along with “Percival Everett,” also Percival Everett.

Though funny, the novel also possesses a terrible and still sadness, concerning as it does not only William Styron and Nat Turner but also aging and death, the tragic hatred of racists, the depth of solitude at life’s end.

“Percival Everett” tells the story of a father, or possibly a son, who’s a writer, or possibly a painter, discovering a daughter, or possibly an impostor daughter. It tells, even more compellingly, the story of an old man, both father and son, who mounts a small rebellion in his old folks’ home, where a gang of orderlies robs and bullies its elderly, vulnerable charges. But the stories it tells are less what “Percival Everett” is about than the shifting identities of its subjects, the permeable boundaries of the narrative self.

If you want me to offer the cons, if you want me to say something gossipy, even snarky, about “Percival Everett” here, I can oblige: To nitpick, I could have done without chapter titles like “Ontology and Anguish” or “Physis/Nomos,” but that was the only negative for me.

Those section names are pretty tongue-in-cheek, I’m guessing, because Everett, though he writes intelligent metafiction, doesn’t take himself too seriously — that is, there’s enough humor in his seriousness to craftily deflect any allegation of pretension.

Percival Everett is a playful writer who mocks both himself and the form charmingly, who’s sometimes even silly, who works in a variety of idioms and genres, dropping in some Italian here or there and maybe something that looks suspiciously like math.

Also, it should be mentioned, I’m personally as a reader likely less educated than Everett. I’m not a professor at all, I don’t know anything about Deleuze. People have sometimes said to me, “Oh, you’re giving a talk? Maybe bring in Deleuze!” But I can’t bring in Deleuze, nor do I wish to, candidly. And I want to apologize for that, both my inability and also my resistance, my conviction that Deleuze had his path, in this life, while I have mine. Point is, I don’t need to be intimate with Deleuze, or similarly lofty textual references, in Percival Everett to know and enjoy him.

And putting aside the chapter titles, as well as my personal failure with regard to Deleuze, I have to say the book, though it’s frequently philosophical, is not in the least boring. Dear reader, how that impressed me! For there are times when philosophy can be less than action-packed. This is not one of them. Therefore, I heartily commend this book to you. It’s like a carnival ride, but not the kind where you vomit.

You never know who’s telling what in “Percival Everett,” much as you’re not sure what kind of confused and solipsistic individual is writing this review, but to me there was much that was pleasurable about that fluidity, that openness, there was something that allowed me to get in there, intruding myself pleasantly and even productively into Percival Everett, or, in any case, the fictional impostor pretending to be him.

Of course, exactly who’s telling which story does not have to matter, in the face of voice; “Percival Everett” knows the primacy of voice. And more than that I won’t say, because the spoilers here aren’t plot spoilers; the spoilers, with a book like this, are of a subtler stripe, and I don’t want to leak any.

Percival Everett has written so many books — among them “Erasure,” “American Desert” and “I Am Not Sidney Poitier” — that he rivals, in prodigiousness, such rampant graphomaniacs as Joyce Carol Oates, while bearing little resemblance to same. I’ve read enough of these books to choke a fat little pony, if not a full-grown horse, but still not enough — and here I’m quite determined to come clean — to exceed more than half, that is, approximately 10.

Despite this, I feel I can safely assert that “Percival Everett” numbers among his very best.

If you don’t know Percival Everett as I do — meaning not personally or actually but sheerly in your mind, with your own brand of presumptuous subjectivity — this would be the perfect moment to meet him. If you’re a fan of long standing, “Percival Everett” is likely to offer you satisfaction — possibly tears — recognition, fear — a sense of desolation. It will offer, and likely you should accept.

Millet’s newest novel, “Magnificence,” was the last in a trilogy about loss and extinction.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.