Review: What do poets Kevin Young, Lucia Perillo and Allen Ginsberg have in common?

A great one-page poem can have all the power and breadth of a whole novel, but no great poet writes just one poem. In a way, a poet’s work takes a lifetime.

To measure a poet’s accomplishment, one must survey his or her writing to date. This February, we have the chance to do just that with three important poets who are publishing retrospective volumes gathering poems from their entire writing lives.

The first is firmly in the mature stage of her career, the second squarely in the middle, and the third is a long-revered major poet who died two decades ago, whose new book offers readers a chance to remember and reassess.

For a poet obsessed with the steady degradation of the body and looming of death, Lucia Perillo manages to be highly entertaining. A MacArthur fellow and Pulitzer finalist, Perillo, who suffers from and writes — implicitly and explicitly — about multiple sclerosis, picks poems from her six previous books and adds new ones in this new and selected volume.

Perillo approaches mortality with a light touch and self-deprecating humor. Long before the final humiliation of death, she notes in poem after poem, there are innumerable instances of minor everyday shame: “this is the problem of the body,” she writes, “not that it is mortal/ but that it is mortifying.” It is the site of the “juicy scab” and “the head... held between the hands.”

Perillo also has other — if related — interests. She worked for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and nature is full of lessons and cautionary tales, as in “The Great Wave,” an ambitious, longish new poem:

Now that we’ve entered the wave of extinction

let’s sing while we still can,

before we all go where the dinosaurs went,

dropping our bones down into the shale—

and the floor of the sea becomes the top

of the mountain, the top

of the mountain the trough of the ditch.

Each dose of hopelessness is met with some kind of call for singing. Even in a poem about being “fatally allergic” to bees, Perillo plumbs the depths with a little joke: “didn’t Robert Lowell say, if people were equipped with switches,/ who wouldn’t be tempted, at some point,/ to flick themselves off?”

Humor is actually the key to the power of her poems: While it’s tempting to assume Perillo jokes to protect herself from life’s dark inevitabilities, in fact, her jokes serve to expose her. She rolls up her sleeves for our benefit, shows us her skin, giving the bees a target.

Meanwhile, over the last two decades, Kevin Young has become one of the poetry stars of his generation, prolifically publishing ambitious collections that mix a wise and witty — and sometimes sexy — swagger with modes borrowed from many sources. Young loves blues and jazz music and has sought ways of adapting their rhythms to poetry.

He addresses a wide variety of subjects and is deeply concerned with the legacies and ongoing aftereffects of slavery in America. His work attests to a belief in the capacity of language to affect the present by reanimating the past.

This first hefty retrospective collection surveys Young’s eight books of poetry, beginning with his remarkable debut “Most Way Home,” published when he was just out of Harvard. A sequence that tours a circus shows Young’s early command of his powers, describing “a still bull/ elephant brought/ and tamed from/ the plains of greyest// Africa…/ acrobats with flesh/ colored costumes lying// beneath his harmless dark/ foot.” Few poets begin with that kind of poise and reserve.

Young’s second book, “To Repel Ghosts,” remains for me his most rewarding. It contains Young’s first masterpiece, the long poem “Jack Johnson,” a capacious homage to the outspoken, pioneering black boxer of the early 20th century. Presented here only in selections, it shows how Young spins a powerful yet humanizing myth:

They call me dog, cad

or card, then bet

on me to win. I’m still

an ace & the whole

world knows it. Don’t

mean most don’t want

me done in. But I got words

for them too — when I’m through

most chumps wish

they were counting

cash instead

of sheep, stars.

Young is capable of talking back to his most imposing forebears, as in “For the Confederate Dead,” which rewrites Robert Lowell’s famous Civil War elegy:

In my movie there are no

horses, no heroes,

only draftees fleeing

into the pines, some few

who survive, gravely

wounded, lying

burrowed beneath the dead--

silent until the enemy

bayonets what is believed

to be the last of the breathing.

Books about his father’s death and his own coming to fatherhood — “Dear Darkness” and “The Book of Images” — are also astonishing and contain some of Young’s best poems.

At just under 600 pages, this book is hardly a culling. Not only does Young print large swaths of his previous books, but he includes many uncollected poems. Among these, a sequence about Phillis Wheatley is absolutely necessary, while various poems written for friends’ weddings could have been omitted. Yet, given how good he is at his best, I’m glad he’s erred on the side of abundance.

Allen Ginsberg was also a poet of abundance, recasting Whitman’s oracular long lines in the roiling rhythms of the American midcentury. This new book surfaces uncollected, sometimes unpublished, poems from throughout Ginsberg’s writing life, spanning the 1940s through the ‘90s.

One doesn’t read this book because these poems in particular are important, but because it’s Ginsberg, whose importance is unquestionable. Among his many roles in 20th century culture — ‘60s protest jokester, Zen ambassador, literary lion — he was also, for many, the gateway poet.

These are not unlike other Ginsberg poems — fierce, funny, libidinous, subversive — but here they afford a fresh chronological tour of Ginsberg’s life, which is also one version of the story of the second half of the 20th century.

It begins with the teenage Ginsberg, well on his way to his mature voice, calling a congressman “half a man—/ The other half/ Republican.” By the ‘50s, he’s in full swing, as evidenced by minor examples of the kind of improvisatory poems that made him famous — “my soul woke/ arm in arm with a youth:/ hours of communion/ warm thighs….” The high point is a long poem called “New York to San Fran,” the book’s most ambitious and fulfilled piece.

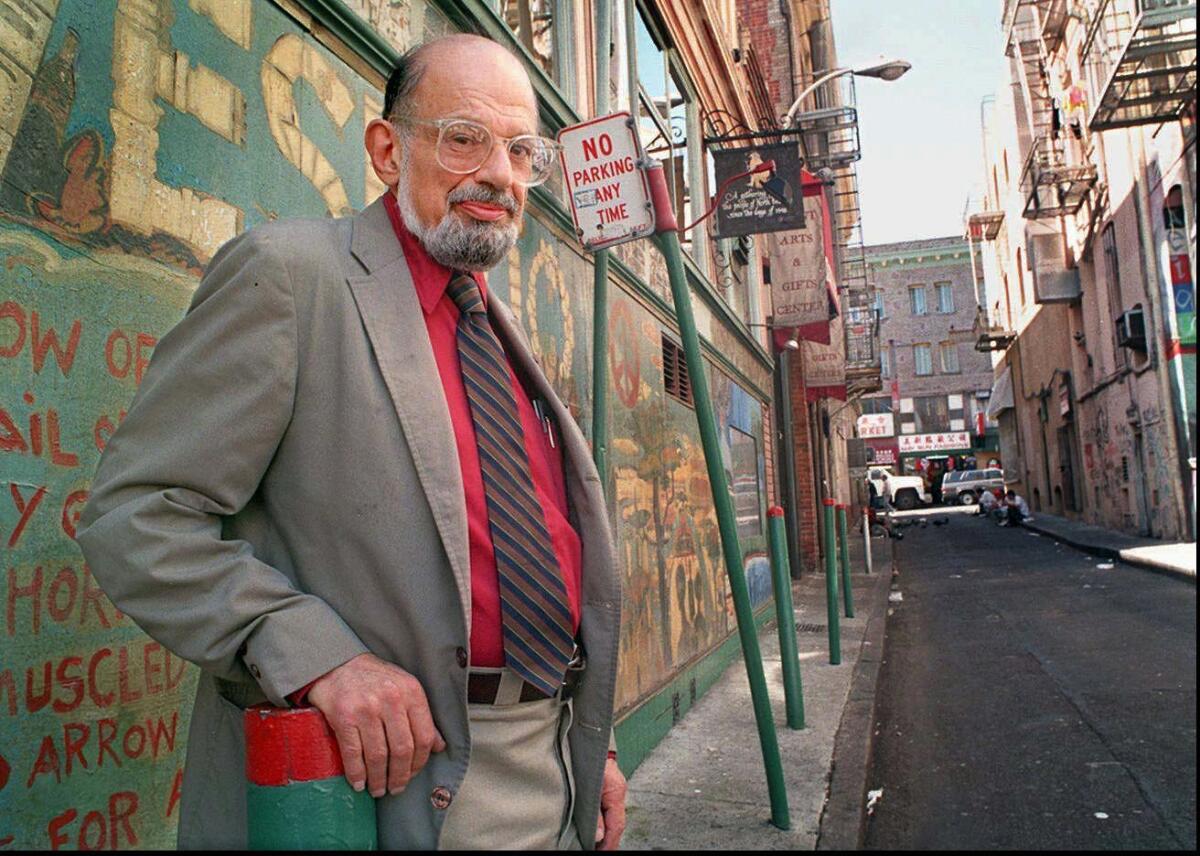

Poet Allen Ginsberg stands in Jack Kerouac Alley next to City Lights Bookstore in San Francisco’s North Beach district in September 1994.

Ginsberg made his own meaning of the present tense: His poems are set insistently in the now; their power isn’t in particular lines so much as the whole aesthetic, the continuous decision to return, again and again, to his own mind and perceptions, like a meditator to his breathing. He treats everything with an utterly absorbing present-tense vividness, which this book lets us view through grown-up eyes.

Poetry is a practice as much as it is a product, a way of living and the evidence left behind. These books show three poets making their own particular kind of sense of the uncertain world. We are lucky to be able to join them.

Teicher is the author of several books of poetry and fiction and the editor of “Once and For All: The Best of Delmore Schwartz,” coming from New Directions in April.

::

Time Will Clean the Carcass Bones

Selected and New Poems

Lucia Perillo

Copper Canyon: 200 pp., $23

::

Blue Laws

Selected and Uncollected Poems, 1995-2015

Kevin Young

Knopf: 608 pp., $30

::

Wait Till I’m Dead

Uncollected Poems

Allen Ginsberg

Grove Press: 272 pp., $22

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.