There won’t be a Nobel prize in literature this year. But we readers have plenty to celebrate

Fully 2,501 years ago last winter, Aeschylus won the first known literary prize. The Dionysia festival, an annual Athenian version of Pacific Standard Time, awarded him an ivy wreath for a play whose title and text are long since lost to history. We know it wasn’t a comedy because, with a bias that persists to this day, the city Dionysia didn’t get around to recognizing komoidía alongside tragoidia until three years later.

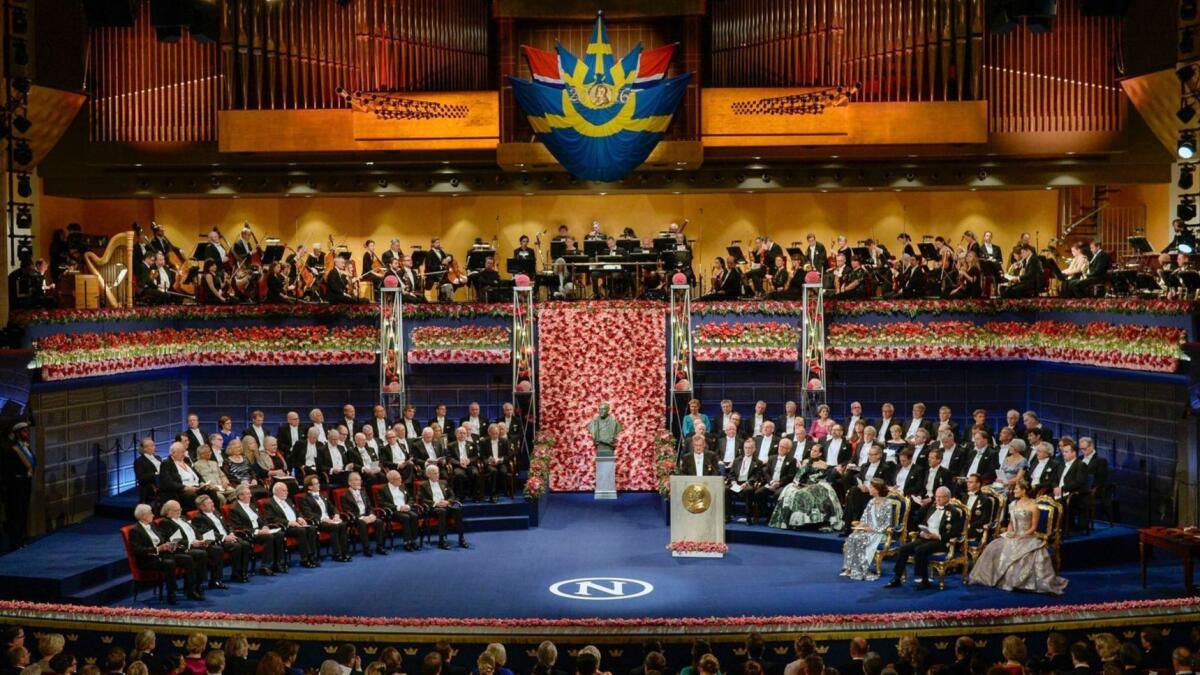

Ever since, literary tastemakers have been giving awards like it’s going out of style — which, somehow, it never has. At this time of year, leading up to the first Thursday in October, literary Nobel-watchers would ordinarily be palpitating with anticipation. All nine of us would be religiously checking the morning line at the (aptly named) British bookmaker Ladbroke’s. For this one week every fall, even English majors seemed to care about literature. “Middlemarch” Madness!

And then the Swedish Academy, which awards the prizes every year, had to go and bollix it up. After assault accusations against the husband of one board member, the resignations began. First one member stood down, then another.

Stung by the scandal, depleted from 18 voters to 11, the academy announced it would refrain from anointing any laureate in literature this year. Instead, like a rock star postponing his scheduled LP to release a double album, it plans to award two Nobel Prizes in literature in 2019.

All this leaves us book folk with a huge spiritual void to fill next month. What are all the pseuds — perpetually on the lookout for the next new writer of the moment — to do?

Make up our own damn minds, that’s what. By the end of this essay I plan to stick my neck out and, at least half-seriously, award my own prize to one living author. What have the Swedes got that we haven’t got? Aside from a 9-million-kronor kitty every year?

Already, because hype abhors a vacuum, others have been getting into the literary prize-giving act. A clutch of Swedish literati calling themselves the New Academy plan to bestow a one-year-only New Academy Prize and then disband immediately. First they worked up a distinguished, if uncommonly YA-friendly, longlist of almost 50 writers. Then the public weighed in and here is the eclectic final four: a Vietnamese Canadian writer, Kim Thúy; the Guadeloupean historical novelist Maryse Conde; the all-ages author of “American Gods” and “Coraline,” Neil Gaiman; and perennial Nobel bridesmaid Haruki Murakami, who has since withdrawn from consideration.

Did Murakami bail because he suspected that — as with candidates for the Oscars’ short-lived popular film category over the summer — taking home a consolation prize might have coshed his chances of eventually winning the real thing? Regardless, the winner will be announced on Oct. 12, and color me at least curious.

But the Swedes are by no means the only ones out there giving loot to writers. They’re not even the richest. The Abu Dhabi-based “Million’s Poet” show, a kind of government-subsidized “American Idol” for Bedouin poetry, boasts a jackpot of $1.3 million. Pre-meds out there, it’s not too late to change your major.

If anybody else is feeling the first twitches of Nobel withdrawal, consider these perennial alternatives:

The Neustadt International Prize for Literature: Awarded biennially by the University of Oklahoma, where the distinguished journal World Literature Today is published, it went to Edwidge Danticat last November. Winners receive a silver eagle feather, $50,000 and an all-expenses-paid trip to Oklahoma City.

The Franz Kafka Prize: Last year the Kafka Society and the city of Prague presented their annual award to Margaret Atwood. In keeping with tradition, she received $10,000, a diploma and the weirdest-looking statuette you’ve ever seen. The Nobel, by the way, makes do with a medal depicting a poet under a laurel tree, taking dictation from the muse, encircled by a quote from the Aeneid. You can buy gold-wrapped chocolate ones in the Nobel Museum.

The Jerusalem Prize: Cruelly, as with the Golden Globe Awards, the biennial Jerusalems are often treated as a mere bellwether for another prize, a kind of high-toned sportsbook. In fact, their batting average as a Nobel predictor is pretty low. Admire the Jerusalem Prize instead for having the taste to honor so many fine writers that the Swedish Academy hasn’t yet got around to, or never did: Graham Greene, Milan Kundera, Ernesto Sabato, Don DeLillo, Susan Sontag and Arthur Miller. The 2017 award went to Karl Ove Knausgaard, whose sixth and supposedly final autobiographical novel just came out to mixed notices and — suspiciously — whose book tour this fall has just been abbreviated to exclude, among other cities, our own.

The Formentor Prix International: The Formentor was the first major prize to recognize Jorge Luis Borges, the great Argentine writer-librarian whose short stories read like lost “Twilight Zone” episodes steeped in a carafe of vermouth. This honor came way back in 1961, when he was still only a few years removed from his first American publication in Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine. Borges actually shared his Formentor — named for the Mallorcan town where it’s bestowed — with Samuel Beckett. No one has yet written a one-act play set in the Formentor green room that year, but it’s only a matter of time.

The Premio Reino de Redonda: Do you know about the century-old Kingdom of Redonda? This uninhabited Caribbean island’s honorary king in exile, at present the Nobel-caliber Spanish novelist Javier Marias, awards a prize every year to deserving writers and artists. Winners receive imaginary Redondan peerages. Ray Bradbury, for instance, was created Duke of the Lion’s Teeth in 2006. It’s somewhat unclear whether the Kingdom of Redonda and its prizes still exist, or indeed ever existed except on paper. Is it all some giant Borgesian hoax? If so, it’s never been completely debunked. Nowadays, what hoax ever can be?

The America Award: John Steinbeck and Czeslaw Milosz are the only one-and-a-half Californians who’ve ever won the literature Nobel. Still, lest anybody think California would rather sit on its laurels than bestow them, Los Angeles gets into the act every year with the America Award. Presented each year by poet and publisher Douglas Messerli’s L.A.-based press, Green Integer — frequently in absentia, because there’s no money attached — this award honors, simply, a “lifetime contribution to international writing.”

This last-named award is the only prize on this whole list that’s honored, or apparently even much debated, my pick for one of next year’s tardy Nobel Prizes. We know they’ll never give a Nobel to Thomas Pynchon and risk another no-show after Dylan, so let’s rule him out. Of the rest of the field, my pick is (drumroll please) the 81-year-old British/Czech playwright and screenwriter Tom Stoppard.

Got a problem with that? What other living author has written a debut play as giddy and groundbreaking as “Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead,” whose worm’s-eye retelling of “Hamlet” all but invented the now-ubiquitous genre of classics turned inside-out? Or “Travesties,” in which a couple of peevish cardholders in the 1918 Zurich public library named James Joyce and V.I. Lenin take a back seat to the machinations surrounding an absent-minded British consul?

In these early Stoppard comedies, major figures become minor characters, and vice versa. Somehow, the wrong end of the telescope is always the only end available. Over the years, though, Stoppard’s omnivorous curiosity has led him down ever more varied byways: philosophy in “Jumpers,” journalism in “Night and Day,” espionage in “Hapgood,” the romance of socialism in “The Coast of Utopia,” and everything from cybernetics to landscape gardening in “Arcadia.”

And what modern play other than “Angels in America” even approaches Stoppard’s incomparable “The Real Thing”? If there’s a better postwar — hell, post-Victorian — English drama about marriage, jealousy, politics, literature, heartbreak and popular music, please mail me a copy. Fingers crossed about his latest, “The Hard Problem,” which has its American premiere this fall in New York.

Stoppard’s screenplays alone would be reason enough to give him the Nobel Prize. He wouldn’t be the first part-time screenwriter to win, either. The playwright Harold Pinter cracked “The French Lieutenant’s Woman” after skeptics had called it unadaptable, and his published Proust screenplay was so good that production could only have ruined it.

Stoppard’s scripts for, among many others, “Shakespeare in Love” and John Le Carre’s “The Russia House” — now there’s a novelist overdue for a call from Stockholm — are equally deserving. He has a screenplay of “A Christmas Carol” making the rounds too, and if anybody can roast that chestnut to a crackling golden brown, Stoppard’s the man.

The knock on him has always been that he’s too witty, too brainy, too playfully word-drunk on snappy banter. And this is bad why? If most people put their minds to it, they can tell stupidity from warmth; why, then, do so many still mistake intelligence for chilliness?

For those who insist on considering a writer in terms of what he represents instead of what he writes, Stoppard’s is still a makeable case for the Nobel. Yes, he’s a British white guy, but he’s also a child refugee from wartime Czechoslovakia and a human-rights advocate since even before his friendship with the late playwright-turned statesman Vaclav Havel.

Besides banter, gender and pallor, the last strike against Stoppard is elitism. In a famous “Real Thing” monologue, his playwright alter ego compares fine writing to a well-carpentered cricket bat and declares, “It’s better because it’s better.” Not the sort of axiom calculated to set Yale English department hearts aflutter lately.

These are parlous times for literary arbiters everywhere, whether they give out trophies or just kudos. Flawed but gifted authors high and low, from Laura Ingalls Wilder to John Muir to Mark Twain, have been lumped together with arrant racists and worse. By next year it may prove even harder for the Swedish Academy, or any other academy, to agree on who deserves inclusion in the pantheon. Even for the blameless, is literary fame, literary or otherwise, really worth risking all the brickbats anymore? Nowadays, it seems — to quote another Nobel laureate — everybody must get stoned.

David Kipen, a former NEA director of literature, now teaches at UCLA and is the proprietor of the Libros Schmibros lending library in Boyle Heights. His book “Dear Los Angeles: The City in Diaries and Letters, 1542 to 2018” is coming from Modern Library in December.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.