Why do we — women in particular — love true crime books?

“Violent men unknown to me have occupied my mind all my adult life,” Michelle McNamara wrote in “I’ll Be Gone in the Dark: One Woman’s Obsessive Search for the Golden State Killer.” Early in the book, she recounts a pivotal moment when she was 14 years old and a young female jogger was murdered near her home. Two days later, McNamara visited the spot where the body was found and picked up the remnants of the victim’s broken Walkman, holding them in her hands. “I felt no fear,” she wrote, “just an electric curiosity.”

This is the genesis of McNamara’s interest in true crime. In particular, it was the killer’s anonymity that haunted her. “I need to see his face,” she writes, slipping into present tense. “He loses his power when we know his face.”

Reading those lines, I felt the frisson of recognition. I’ve consumed true crime since first discovering “Helter Skelter” by Vincent Bugliosi in a used bookstore at age 9 or 10 and staring in fascination and horror at the crime-scene photos in the middle. And, while the primary focus of “I’ll Be Gone in the Dark” is the Golden State Killer, a ski-masked serial rapist and murderer who terrified the West Coast in the 1970s and ’80s, it also serves as an exploration of the intense attachment many of us have to true crime — in particular, women.

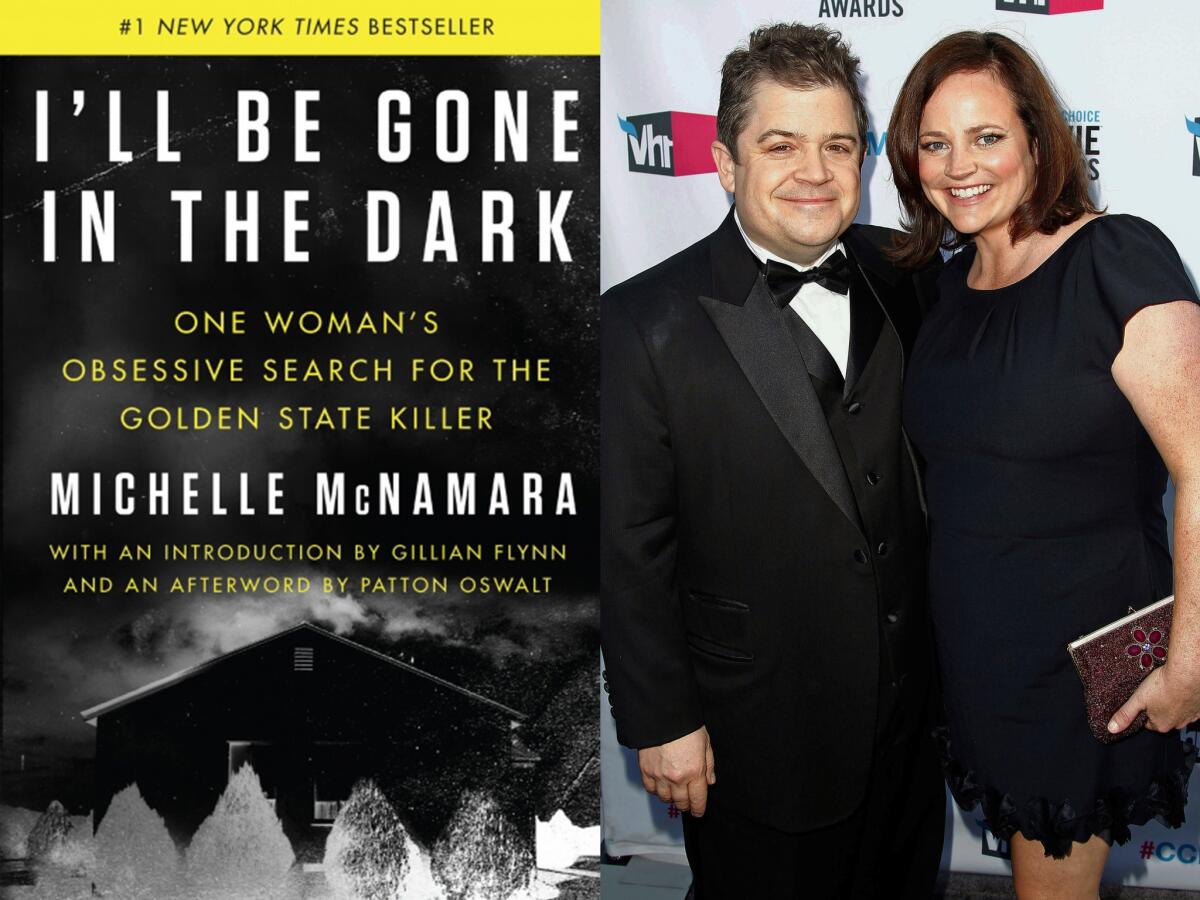

McNamara’s book, completed and published after her untimely death in 2016, landed at the top of the bestseller list at a time when the appetite for true crime feels greater than ever. The conventional wisdom is that its audience is primarily female — a belief supported by an oft-cited 2010 study in Social Psychological and Personality Science, which found that, based on analysis of reader reviews and book selection, women were significantly more drawn to true crime than men. But perhaps the most telling finding of the study is that women were far more likely to select a true crime book featuring female victims. That intense identification between reader and victim ripples violently through McNamara’s book.

But in a recent piece on women and true crime, Cammila Collar finds canny parallels between the recurrent subjects of true crime (love-gone-wrong, family conflict, domestic violence) and the hard numbers on gender and violence. While men are four times more likely to be homicide victims, women comprise 70% of victims killed by an intimate partner, twice the rate of men. (The majority of male homicides are drug- and gang-related.) The statistic that most jumps out at me comes from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Nearly 44% of American women have experienced some form of contact sexual violence in their lifetime and reported some form of impact, ranging from injury and fearfulness to missing work or school or experiencing symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder.

These statistics refute any notion of true crime as escapist fare. As someone who reads the genre avidly, both “high” (Robert Kolker’s “Lost Girls,” Monica Hesse’s “American Fire”) and “low” (ripped-from-the-headlines mass-market books you used to find on the spin rack of your drugstore), I’ve always had a network of fellow devotees, mostly women, to whom I reach out regularly on the latest book, documentary, podcast like the L.A. Times’ “Dirty John” or the breaking news on an old case. Perhaps because it’s long been a “suspect” genre — at best a “guilty pleasure,” at worst a genre for ghouls, for rubberneckers — these exchanges often have a furtive, heated quality. A slightly dirty secret we keep.

But in the last few years, and especially in recent months as the Harvey Weinstein and associated scandals have dominated headlines, I’ve come to think of true crime books as performing much the same function as crime novels (also dominated by female readers): serving as the place women can go to read about the dark, messy stuff of their lives that they’re not supposed to talk about — domestic abuse, serial predation, sexual assault, troubled family lives, conflicted feelings about motherhood, the weight of trauma, partner violence and the myriad ways the justice system can fail, and silence, women.

While these weighty issues aren’t generally resolved in true crime (to the contrary, given the number of them like McNamara’s and Kolker’s in which the case remained unsolved at publication), these books provide a common site to work through crises, to exorcise demons. I’ve come to believe that what draws women to true crime tales is an instinctual understanding that this is the world they live in. (Emailing me about “I’ll Be Gone in the Dark,” a mutual true crime enthusiast — male — noted, “How a man could rape 50 plus women and kill 10 people and get away with it is basically a primer on institutionalized misogyny.”) And these books are where the concerns and challenges of their lives are taken deadly seriously.

It’s been interesting to ponder the question of women and true crime in recent months amid our #Metoo moment. If, for decades now, true crime served as the collective unconscious of so many women, all the taboo topics the culture as a whole represses, what happens when the culture is unable to repress them any longer? In the aftermath of the 2016 election, and the subsequent explosion of #Metoo revelations, all those issues that have always dominated true crime are taking center stage. If true crime frequently explores the abuses perpetrated by seemingly upright men in power — police, sheriffs, elected representatives, district attorneys — well, what happens when these stories fill our daily headlines? The impact can be devastating — not because anyone’s surprised (what reader of true crime could be?), but because we never guessed the lid would be taken off. And now, the onslaught is ceaseless.

Perhaps this is why the finale of the “Dirty John” podcast is so satisfying. It begins as a tale of female victimhood, but in the end it becomes a testament to female intuition and survivor instincts. The script is flipped, and women are weaponized.

This is certainly the feeling reading “I’ll Be Gone in the Dark,” and what marks it as uncannily prescient of our moment. One of the vanguard of “amateur sleuths” who connected on the internet to attack cold cases, McNamara firmly believed that the Golden State Killer would be caught and in fact saw her book as an intervention. This missionary zeal gives her book a potent avenging-angel quality.

Recalling the anonymous killer of the female jogger that sparked her true crime obsession, McNamara notes, “The hollow gap of his identity seemed violently powerful to me.” That’s the power she seeks to tear down, and her defiant energy bubbles through the entire book, reaching its apogee in the blazing epilogue. Framed as her letter to the Golden State Killer, it’s a tour de force of righteous anger. Asserting that technology will ultimately beat him, McNamara warns him, “A ski mask won’t help you now.”

“Open the door,” she demands. “Show us your face.”

In late April, we saw his face. Two years after McNamara’s death and a little over two months after the book’s publication, an arrest was made in the Golden State Killer case. Joseph James DeAngelo, a former police officer, was taken into custody outside the home he shared with his daughter and granddaughter.

Watching the arraignment that followed, with a blank-faced DeAngelo rolled into the courtroom in a wheelchair, I wondered what McNamara would think, if she would feel a sense of catharsis or victory.

Amid the torrent of news about the latest sexual assault scandal, the latest public figure toppled by gross misdeeds, feelings of satisfaction, of justice served, are more elusive. What happens, after all, when the killer is unmasked, yet he turns out not to have one face but many, replaced every few days by another powerful man with yet another trail of female victims in his wake?

Abbott is the author of nine crime novels. Her latest, “Give Me Your Hand,” will be published July 17. She is on Twitter @meganeabbott

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.