Lucia Berlin’s new books: An illuminating memoir, more sublime stories

“Welcome Home,” a memoir patchworked from the autobiographical notes, letters and photographs of Lucia Berlin, features a list: “The trouble with all the houses I’ve lived in.” At 33 entries long, it roams from Alaska to Montana, around the American Southwest, and to Chile, Mexico and finally California — and even this is an incomplete accounting of Berlin’s homes. “Corrales Road,” reads one entry: “No running water, no electricity, no bathroom. Two kids in diapers.” Later: “Yelapa, Mexico — Sharks, scorpions, coconut grove — THUD THUD — three kids. Hurricane.”

Here’s Berlin’s great gift — or, one of them: the power to spark life on the page using the sparest of words. “THUD THUD,” she writes, and we’re in a beach hut in Mexico. This economy of vivid expression captivated readers and critics in 2015, when the posthumous collection “A Manual for Cleaning Women” finally won the prolific short-story writer the fame that had always eluded her, 11 years after her death.

Equally captivating is the life those spare words paint. Berlin’s stories are drawn straight from her life — if she were writing today, she’d be championed alongside Rachel Cusk and Karl Ove Knausgaard as a master of autofiction, though she’s distinguished by having led a life more interesting than most fictions. As the list of her homes suggests, her 68 years were almost impossibly full of travel, adventure, loves found and lost, alcoholism and its defeat, and the struggle to get by as a single mother of four boys. These themes and plots sang through “A Manual for Cleaning Women,” and though “Welcome Home” is a little thin, there’s a delicious pleasure in tracing the nonfictional origins of Berlin’s fictions. Even more deliciously, “Evening in Paradise,” a follow-up short-story collection, brings new fictional renderings of this astonishing life, and reveals just how full a body of rich work Berlin left behind.

If it was almost impossibly full, Berlin’s life was also almost impossibly restless. Her son Mark has estimated that his mother moved every nine months, on average. Partly, this is a story of struggle, the rootlessness that comes with financial instability. The moving also perpetuated a rhythm established in Berlin’s childhood, spent hopping mining towns around the U.S. and Chile for her father’s career.

But read the stories in “Evening in Paradise” and you soon see that there’s more to the restlessness. It externalized an internal drama: there was something in Berlin that she couldn’t quite reconcile, but maybe the next place would fix it, or the next, or maybe the act of moving itself. In the title story, Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton laugh with John Huston in a hotel bar in Puerto Vallarta. It’s the early Sixties, a party during filming of “The Night of the Iguana.” Taylor “was warm and lovely. She and Burton had big booming laughs, were simply in it, each other, the place, the life.” “Simply in it”: the highest of praise from Berlin, whose letters to her friend Helene Dorn, published in “Welcome Home,” resound with biting self-criticism: she wonders “how to stop imposing things on myself, to get out of myself and just be.”

She seems to have found this freedom, the ability to “just be,” only in movement. In a letter to Helene and her husband Edward Dorn, Berlin’s mentor, she describes flying on her third husband’s plane: “between the land and sky and the weather, you are part of the whole world.” Compare the story “Cherry Blossom Time,” from “Evening in Paradise,” about a young mother crushed under the weight of routine. In a pet shop, she’s horrified by a cage of mice “running around in berserk circles” — circles much like those she runs with her toddler. “What’s the matter with me?” she frets. “What more do I want? God, let me just see the good things.”

This anxiety with stillness creeps into Berlin’s stories at the structural level too. A rhythm recurs in “Evening in Paradise”: a moment of bliss swells, bubble-like, then pops. In a standout story, “Andado,” a 14-year-old girl enjoys a sumptuous weekend on a Chilean estate — breakfast in bed, horseback riding, flirting with her dashing older host — until the host forces the flirtation too far, into what would now be considered rape. (Berlin positions the incident in a gray area.) “La Barca de la Ilusión” takes us to an American family living in Yelapa, Mexico (THUD THUD), where “[d]ays and months passed in an easy rocking rhythm. Just before dawn the roosters crowed and at the first light a thousand laughing gulls flew past the house upriver.” But an old heroin connection tracks the father down, and pop goes the bubble. It’s a rhythm of paradise found and lost, found and lost, until a ruinous end comes to seem intrinsic to happiness. If bliss is always tinged with the fear of its own loss, best to keep moving.

Berlin yearned to surrender to the flow of life, in stillness or motion. The trouble is, “simply in it” isn’t a writer’s way of being in the world — writers observe, hold back. This left Berlin painfully stuck between her enormous appetite for life and her gift for observation. In motion, she could temper that remove, but as a writer through and through, she would never fully escape it.

After “A Manual for Cleaning Women,” Berlin was feted as one of the 20th century’s greatest chroniclers of work and domestic life. It’s true she was gifted in writing these spheres, and true too that the subject matter might have kept her in the shadows, since even today domestic fiction by women is often dismissed as lowbrow or trivial.

But the label doesn’t do justice to the scope of her work or her spirit, this lifelong drive to “get out of herself and just be.” She was no kitchen-sink realist. Time and again, the stories reveal that her subject wasn’t domestic life but life itself, which for her often happened to be filtered through the domestic. This comes through in the sustained tension between rootedness and movement, the domestic and the sublime. In “Lead Street, Albuquerque,” a young woman married to a bad painter stands on her front steps during a party, “too depressed to call anybody to come see the unbelievable sunset.” Go looking, and you’ll find this in all of Berlin’s domestic scenes: the unspoken sense that there’s an unbelievable sunset going on somewhere, if only the characters could gather themselves to find it. This tension is the magic of Berlin’s work.

There’s a hint in this new collection that she later found ways to reconcile her conflicting impulses. “Lost in the Louvre” tells of a late-life, solo trip to Paris. The protagonist feels that she’s passed through life as she does the Louvre, “watching and invisible” — far from “simply in it.” But by getting lost among the exhibits, she touches the sublime, “losing myself until I felt as if I were flying out of time.” She seems to have found a way to accept the role of spectator (in the museum, in life), and to find transcendence precisely in this role. To be simply in herself.

“Dying is like shattering mercury,” says this protagonist. “So soon it all just flows back together into the quivering mass of life.” The pity is Berlin never knew that, thanks to her sometimes painful gift for watching, it will be many years before her story flows back into that quivering mass.

Robins is a writer and translator in Los Angeles.

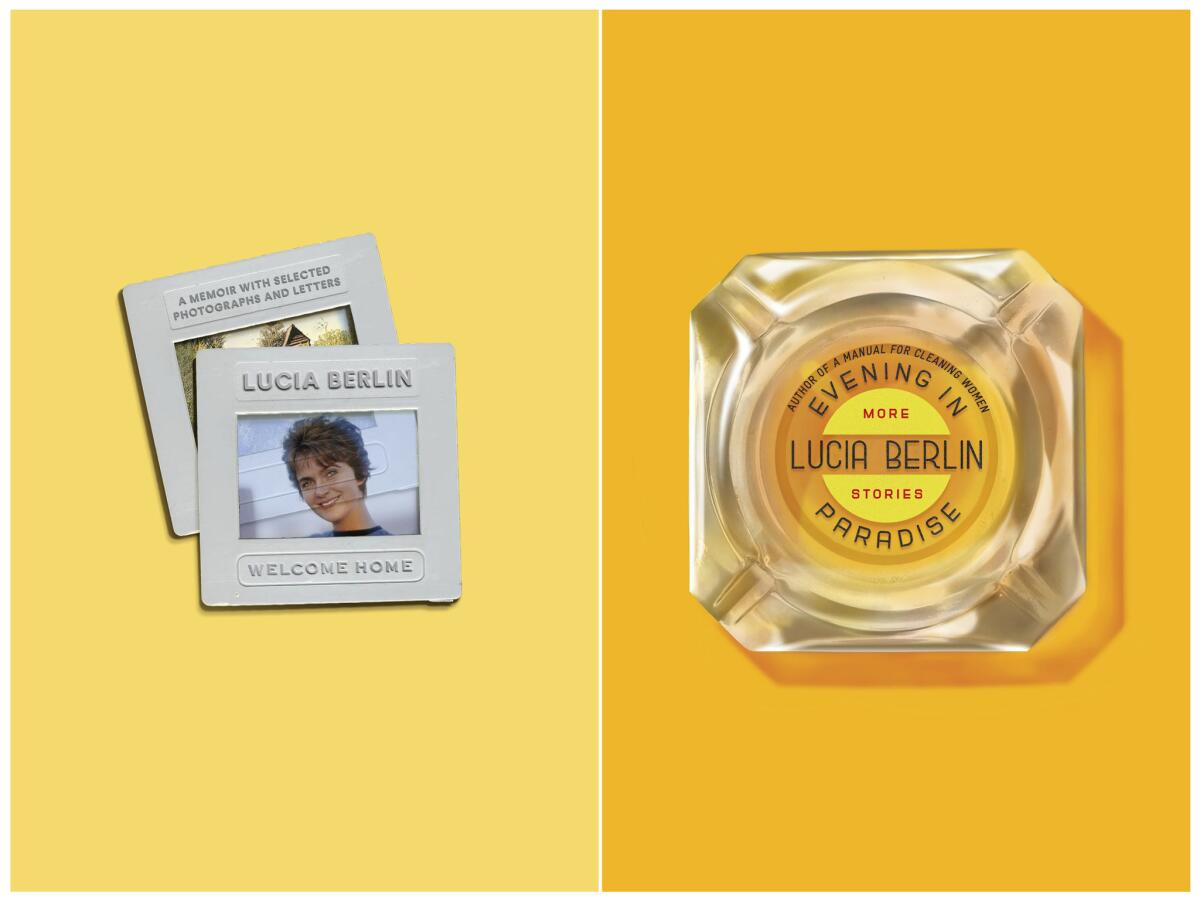

“Welcome Home: A Memoir with Selected Photographs and Letters”

Lucia Berlin

Farrar, Straus and Giroux: 176 pp., $25

::

“Evening in Paradise: More Stories”

Lucia Berlin

Farrar, Straus and Giroux: 256 pp., $26

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.