Review: Karl Ove Knausgaard’s latest shows there’s more to Edvard Munch than ‘The Scream’

“Many had painted oaks before,” wrote poet Olav H. Hauge. “Nevertheless Munch painted an oak.” This seems about as profound a thing as one can say about painting, which is wordless and beyond words.

Karl Ove Knausgaard’s treatise on the art of Edvard Munch, “So Much Longing in So Little Space,” fails — as art criticism is prone to do — to adequately “read” or “translate” Munch’s paintings for us. But it should not be expected to be a translator. (Art criticism obviously can’t use the language of the thing it’s critiquing in a way literary criticism can, which is a problem Knausgaard recognizes in the book itself.) And yet, though the book fails in the ways it must, it succeeds where others have failed, in its ability to imbue its failure with its own blend of artifice and truth, cliche and possibility, openness and closedness, creating something that may prove to be classic.

Ostensibly “So Much Longing in So Little Space” is a book of art criticism, but it is as much about its author as it is about its subject. Here we witness Knausgaard interviewing various artists and critics, fretting over a speech he must make on Munch because he cannot find a “unifying element” in the artist’s oeuvre, doubting his own curation of an exhibit of the painter’s lesser-known works for the Munch Museum, visiting Munch’s houses even though he is “not really much in favour of a biographical approach to art,” and filming a movie with Emil and Joachim Trier.

Thus, the book feels of a piece with the autofiction for which the Norwegian novelist is best known.

Knausgaard’s “My Struggle,” which took the literary world by storm over the last decade, is a 3,600-page, six-volume autobiographical novel that recounts in unsparing quotidian detail the life of a man writing a 3,600-page, six-volume autobiographical novel.

It makes sense, then, that such a prolific author would be attracted to a painter as prolific as Munch, who created more than 1,700 paintings throughout his life — but this is but one of a number of kinships connecting these two Norwegian masters.

As Knausgaard searches for that unifying element in Munch’s work, he stumbles upon certain truisms on the subject of art (“no art is free of morals,” “art is as much about searching as it is about creating,” “only those works that break with the era come to be seen as typical of the era”). What is so compelling about the book, though, is that this longed-for unifying element and these supposed truisms become themselves suspect as the book approaches its terminus.

The reader likely won’t agree with all of Knausgaard’s thoughts on Munch, but that’s OK, because he seems hardly able to agree with himself. He’s continually pivoting, contradicting, prevaricating. In one moment, he describes Munch’s “openness to the world” as a potential unifying element, only to admit a couple of pages later when discussing Munch’s painting “Woman in Three Stages” that “no one could say that ‘Woman in Three Stages’ stood open to the world.”

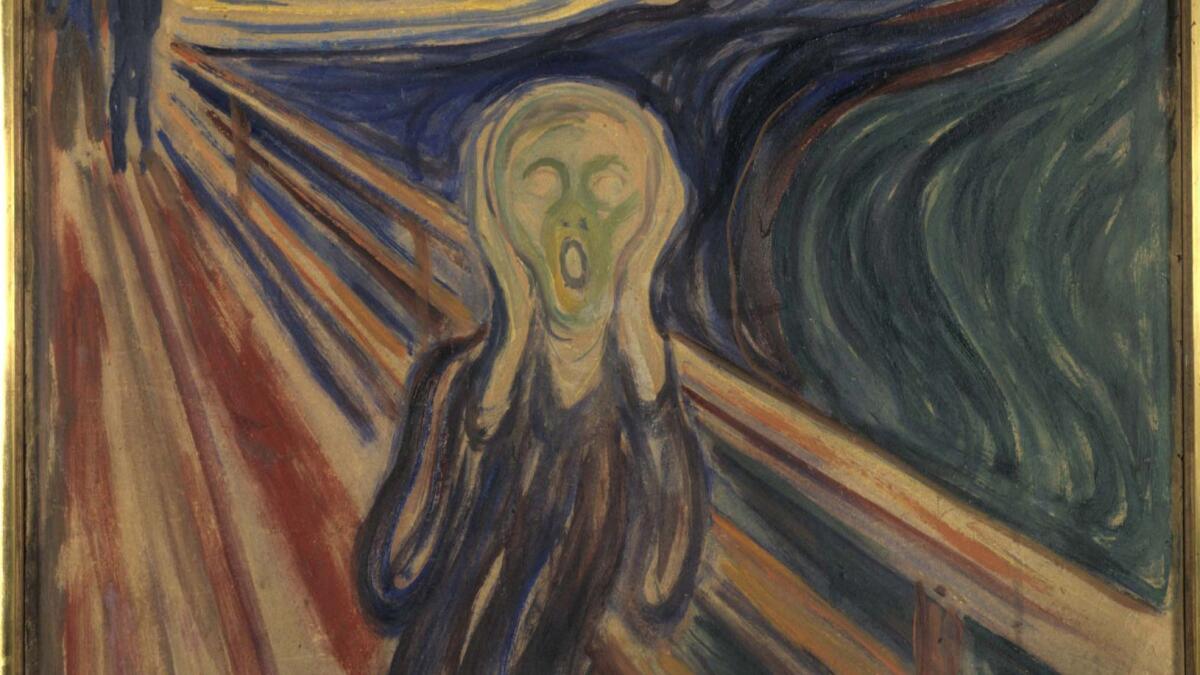

Elsewhere, he determines that “a painting should explore that which is specific to painting,” which seems in some way a thesis of the book, that painting at its best achieves things that only wordless paint can, each medium of art to each. Yet this is challenged when he argues that some of Munch’s paintings, especially the ones from the 1890s for which he is most known, do the opposite, using an iconography, certain forms of expression, which can be transposed into other media.

“There are no rules in art, only conventions,” he admits, so that even his idea that each medium is at its best when it uses the qualities that are specific to that medium is understood as nothing more than a convention of modernism, a fad of our current moment.

When “So Much Longing in So Little Space” fails at finding a unifying element, and as it continually backs away from many of its initial pronouncements, there is more to be gained than lost, for the book is less about cataloging an understanding of an artist’s works and more about exploring, in its own medium, with its own form, and on its own terms, “the fluid zone between the world in itself and our image of it.”

Just as much of “My Struggle” is spent on recording the beauty in the banal, Knausgaard’s newest book spends as much wordspace on the works by Munch that are “insignificant and perhaps hardly worth a mention,” some of which have never even been exhibited for the public, as on the monumental 1890s works from the “Frieze of Life,” like “The Scream” and “Madonna.” He is interested in both the major and the minor — gives them equal footing. In doing so, he’s mirroring Munch: “By giving the same attention and weight to all his motifs, Munch demonstrated that to be a human being in the world is the same everywhere, and that significance lies within ourselves.”

Knausgaard, like Munch, is interested in particulars and universalities, and the interchange between the two. “Munch sees what is unique about this landscape,” he claims, “not that it differs from other landscapes, but the unique aura it possesses, which only this place has — and this is what he paints.” Knausgaard likewise sees what is unique about each Munch painting — not that it differs from other paintings, but the unique aura it possesses, which only this particular piece has — and this is what he writes.

Yet he knows that “everything that has been thought and written in this book stops being valid the moment your gaze meets the canvas,” and he somehow still soldiers on, courageously, shamelessly, into the inevitable failure that is putting language to paint, transposing the stillness, silence and shapes of visual art into the crude symbols of the alphabet, the progression of narrative, and the flutter of pages.

Many had written on Munch before. Nevertheless Knausgaard wrote on Munch.

::

‘So Much Longing In So Little Space’

Karl Ove Knausgaard

Penguin Books, 256 pp., $17

Malone is a writer based in Southern California. His work has appeared in Lapham’s Quarterly, Literary Hub, the LA Review of Books and elsewhere.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.