Reading ‘Brave New World’ in Aldous Huxley’s former home

Seated on a veranda high in the Hollywood Hills, a few book clubbers who had gathered to discuss Aldous Huxley’s “Brave New World” in the author’s last Los Angeles home craned their necks.

They weren’t peering at the softening evening sky or at the Hollywood sign, which loomed so close it looked like white plastic lawn furniture, a prop to rest a drink on. The occasional helicopter had already torn past, momentarily drowning out voices (“a humming overhead had become a roar,” as Huxley describes their sinister advance in the novel’s climactic scene) but that hardly merited a pause in conversation.

No, during a deep-dive into one of literature’s most compelling dystopias, someone had spotted a drone.

True, surveillance is the territory of a different literary dystopia, George Orwell’s “1984,” but for a moment, the intrusion felt eerie. Was it watching us? And what would Huxley have made of a drone hovering over his roof?

Because a book club at Huxley’s house held the romantic promise of somehow connecting to the author more deeply, we were looking for him everywhere.

A reader in attendance, Hiawatha Bradley, ventured that the opiate of the masses “just has to be technology,” adding, “your brain is wired to the phone.” Alex Hoffmaster drew a parallel between social media and “Brave New World’s” drug Soma, which keeps society numbly happy and subservient. The dopamine hit of a text alert, the Pavlovian thrill of a retweet, are modern addictions. Was that Huxley’s prescience reaching across the veil? A brave new world indeed.

A next-level book club

How did roughly two dozen people find themselves in the unique situation of discussing “Brave New World” at the home of the author? Never underestimate the power of a book club.

This particular group, which is based in San Francisco, has been around for less than two years and often brings in authors to discuss their work, including Jade Chang and Laura Albert (the real JT Leroy). They had scientists from Berkeley’s SETI research center weigh in on Chinese writer Cixin Liu’s science fiction novel “The Three-Body Problem.”

When the chance arose to take up “Brave New World” in the very house where Huxley lived, which is owned by a friend of book club organizer Sarah McBride, it was time for a pilgrimage. Bay Area members flew from Oakland to Burbank, and a number of locals rounded out the party.

“To be discussing the book in a place that was significant to the author,” said McBride, felt like “an extra-special tribute.”

Huxley’s Los Angeles

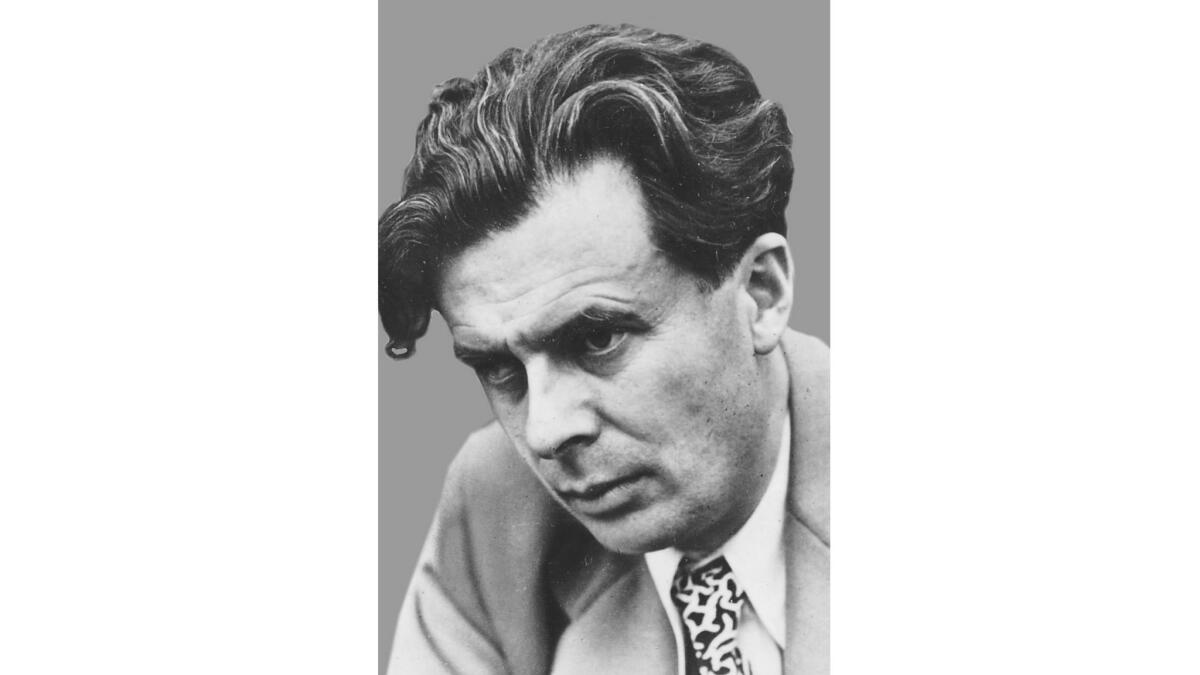

Huxley moved to Los Angeles in 1937, five years after publishing “Brave New World.” He worked as a screenwriter, studied Vedanta Hinduism (with fellow British expat Christopher Isherwood) and famously became an early proponent of psychedelic drugs, which he wrote about in “The Doors of Perception.”

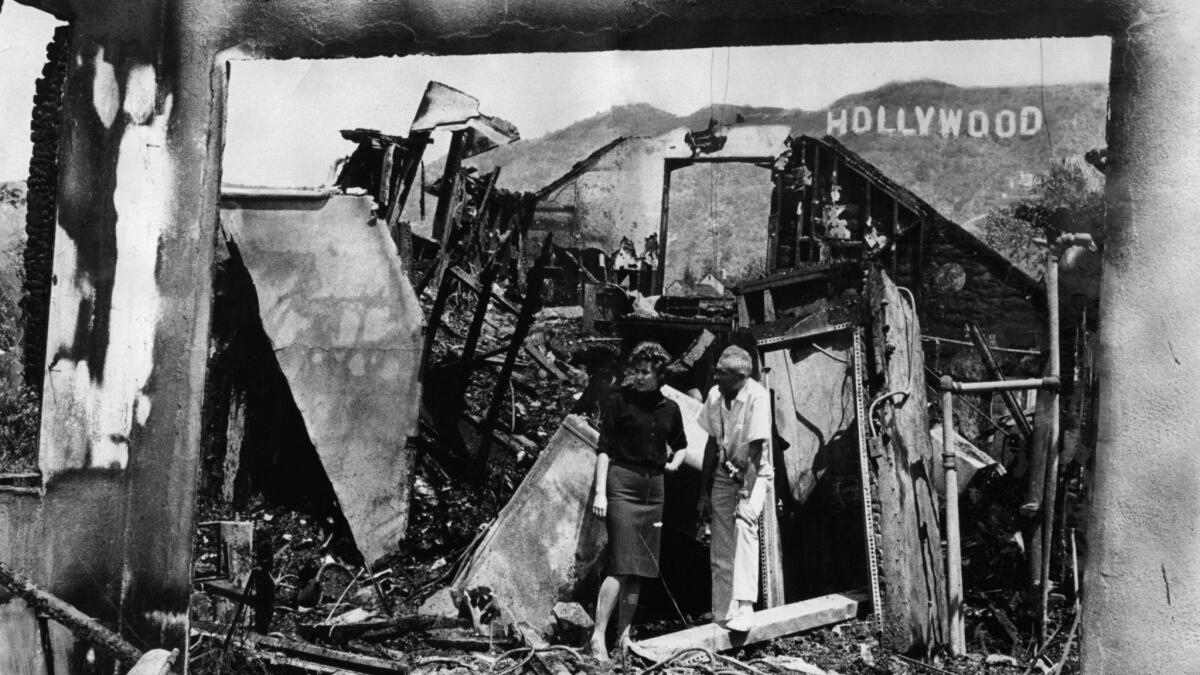

“L.A. at that time must have been like Paris at the turn of the century,” mused book club member Aida Jones as a three-tiered fountain gurgled from the other end of a spacious patio. Huxley moved here after his previous home in the canyon had burned down in a 1961 wildfire.

This was the house where, on his deathbed, Jones announced, “his wife gave him a shot of LSD to his throat.” It was somewhat discordant to think of Huxley expiring on the premises while nibbling book-club fare like cheese doodles and salami, but we were there, after all, with a purpose, and it was clear that people had a lot to say.

Today’s new world

McBride moderated the roundtable discussion, which touched on the maternal bond and authentic attachment, Christian allusions and even the role of scent in the novel, but returned again and again to Huxley’s striking prescience.

Huxley was on the mark about “our appetite for reality television,” said Steven Wong; Jones added that “he foresaw the birth control pill.” Rocket travel, genetic engineering, virtual reality, antidepressants and even the Kardashians were all argued to find precedent in the novel.

But the moors of his era had prevented him from imagining one kind of social change.

“It’s a pretty sexist world,” said Geoffrey Fowler. Josh Levine agreed: Huxley “could imagine so much, but he couldn’t imagine equality.” Kate Connally, who’d been passing out the evening’s “soma” (white wine), thought Huxley’s lead female character Lenina “deserved a deeper portrayal. She’d be played by like, a

Searching for Huxley

McBride mentioned a couple of rumors about Huxley’s promiscuity later in life. “So, when he lived here?” asked Connally. A few people giggled. It was one of the few times the fact that we were at Huxley’s former home was addressed directly. Later, when Miryana Isabella Babic alluded to a “theory that part of the house is haunted,” and McBride offered to show me the room where Huxley died, I felt voyeuristic but eagerly said yes. Huxley — a half-blind Englishman, ever in the musty suits of an academic, at 6 feet 4 towering over the rest of us both physically and intellectually and towering, to some extent, over dystopian fiction — maybe I’d get a sense of him there. It was dark at this point, the hills across the canyon an inky black.

I shuffled into a bedroom, tastefully decorated, and felt nothing. No spirit of Huxley lingered. Luckily his work is easily found.

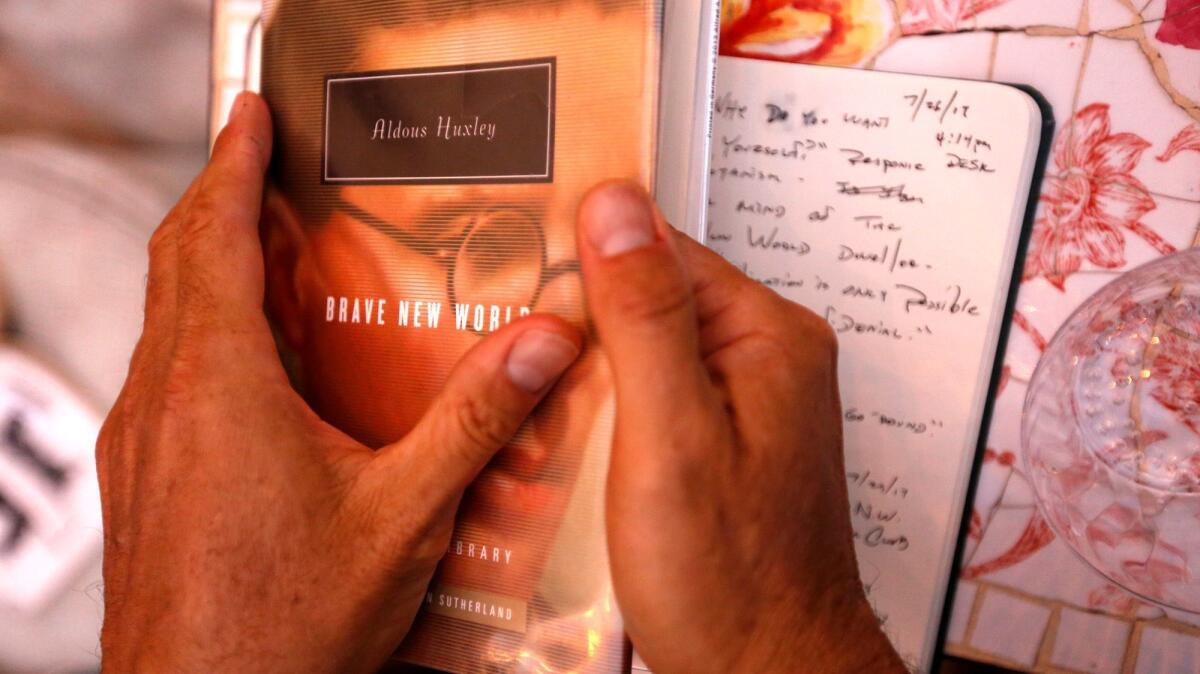

It had been a wonderful novelty to talk about a book he’d written in a home where he’d lived, and though the conversation was erudite and discussing works of art is vital, there’s no closer connection that I know of — across decades, even death — than the page. I’d taken “Brave New World” out from the library for a refresher; it “Brave New World” was waiting at home on my couch.

“The strange words rolled through his mind;” he writes of his tragic hero, John the savage, discovering poetry for the first time. “Rumbled, like the drums at the summer dances, if the drums could have spoken … beautiful, beautiful, so that you cried … because it talked to him; talked wonderfully and only half-understandably, a terrible beautiful magic.”

Yes, there he is. There.

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.