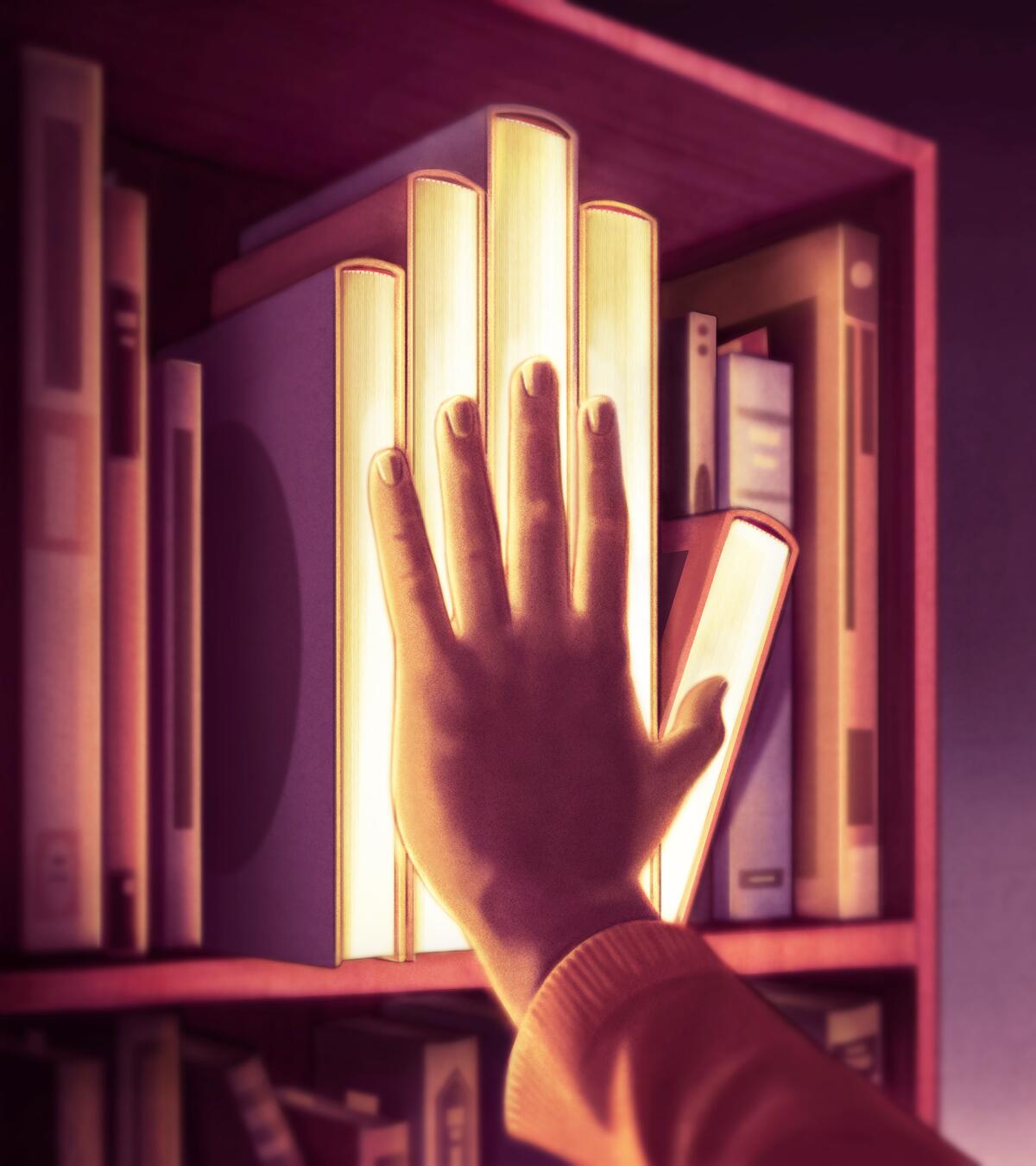

Books we hold in our hands come to life in our hearts

As I write this, at the end of the year, turning the pages of a small tattered paperback copy of “Giovanni’s Room” by James Baldwin — the pages edge-browned to the color of old tea, the thin black cover lovingly library-taped to the small soft body, the way a child repairs a favorite stuffed animal, with big awkward stitches — I think of books in all their frailty and their resonant presences.

For me, books are not just carriers of meaning, but also a presence in the physical world. Am I the only one who cringes to see “sculptures” made of books — desks and beds and armchairs — anxiously perusing their spines to see if a good book has been so abused by a post-literate culture?

This Baldwin is a cheap little Dell paperback, published in 1964 — eight years after its original publication by the Dial Press. Small enough to fit in the back pocket of a pair of jeans, it has that slightly perfumy old-paper smell which prepares me for nostalgia. It was published in a year of political and social transition, 1964 — the impetus, I’m sure, to re-release it in paperback.

I had never read it before, I don’t even know how or when I acquired it. But now I will always think of this Dell edition as my “Giovanni’s Room.” I love its little dedication on the copyright page and epigraph from Whitman. I’ll remember that I had taped the cover back on with library tape — never Scotch tape — and cut up a stiff postcard ad for a ballet whose black matched the jacket, to provide a missing top edge. The novel will always be linked in my mind and my senses to this particular edition, this lovingly patched volume.

This is how I feel about books.

For me, books are not just carriers of meaning, but also a presence in the physical world.

I can’t separate the book from the book, the content from its form. To say, “The Collected Works of Carl Sandberg” is an abstraction. But my “Carl Sandberg” was the first book I ever bought for myself, a fat, gray, hardbound volume with a red square. It had lost its cover who knows how many decades ago. A junior high friend turned me on to the long poem “The People, Yes,” and I had to have it. I made a pilgrimage to Pickwick Bookshop on Hollywood Boulevard at McCadden — the jewel of what once was Booksellers’ Row — where I plunked down my hard-saved birthday and allowance money and took that book away with me. That volume has accompanied me through every move, and when I gaze across the room, it’s like Sandberg himself keeping me company, faithfully, all these years.

We always remember childhood books in tactile form. The green shredded cover of “Beautiful Joe” — already old when I received it in a box from an older cousin — “The Sword in the Stone,” jacketless, chunky, navy blue, with its beautiful little line-illustrations. “Misty of Chincoteague” and “Wind in the Willows,” “The Black Stallion.” The Little Golden Books.

But adult books too have their personalities. My shredded hardbound copy of “Roget’s International Thesaurus, Third Edition” is a beloved friend — the black spine, the rust-colored cloth boards, wide Scotch tape strips holding the covers on, the finger tabs — it has been with me since high school. Its old bookplate, Hokusai’s 19th century piece “The Great Wave, Off Kanagawa,” and my teen-flourish of a signature date it exactly. I have written nothing since 1970 without this book within arm’s reach.

I can’t separate the book from the book, the content from its form.

In a bookcase at the top of the stairs, my cache of old James Bond novels in full-trashy Signet editions, 50 cents each, beckons, rescued from my father’s library (he was a highly literate man but never above a good mystery or trash thriller). I get a special kick from using his volume of “From Russia With Love” to teach scene-writing techniques to graduate students. It’s not any edition of “FRWL,” it’s “my” Bond.

I cannot discuss book-love without mentioning my big bundle of Joyce Carol Oates mass-market paperbacks by Fawcett from the ’60s and ’70s — their white covers with painted illustrations and sassy serif type — edge-browned and often spattered with my mother’s hair dye. (She would read them as she waited for her dye to set.) These were the volumes I studied when I was learning to write.

When I look at them, I see a palimpsest — the darkness and urgency of the stories, my mother with a towel around her neck in the downstairs bathroom, the smell of the dye, the picture of a spiritual-looking young Oates on the back, my markings in the margins as I worked to understand how this fiction was created, and that era when great literature was sold in drugstores and at supermarket checkout lanes.

On the other end of the spectrum is a recent acquisition — a set of aqua-blue top-gilded writings by the naturalist John Burroughs, printed in 1906. This treasure caught my eye at the Mysterious Bookstore on Glendale’s Brand Boulevard. I had attended his namesake’s junior high, and though I’d read John Muir, had never read Muir’s Eastern counterpart. After a year of dithering, I returned during a sale to ask if they still had it. They had to pull out a bookcase to get to the shelf in which the 12 small volumes lay in secret, waiting for me.

Many of the pages are uncut, and I have the very un-modern pleasure of reading it with an X-Acto blade in hand — slicing the creamy pages apart — to the horror of real collectors who save their treasures and purchase second “reading copies.” To me this is repulsive, like not allowing a child to play with a “collectors-edition” Beanie Baby. I want that tactile thrill of reading the thing itself, whether it’s a falling-apart “Upon the Sweeping Flood” in a drugstore edition or Burroughs’ “Winter Sunshine.”

For me, the book is a representation of its contents and its author. My “Anna Karenina” is a large print edition I found in the old downtown Goodwill. Bulky enough in an ordinary edition, the large print is stupendous — but there is something Tolstoyan about its girth. I look at it on the shelf and it is Tolstoy. My tiny white volume of “Winged Seed” by Li-Young Lee is that poetic soul and his story. I love the grainy matte covers and ivory pages of books published by California publisher Black Sparrow. How can I separate Wanda Coleman and Diane Wakoski and John Fante from these particular editions? The black-and-white New Directions books, the little square City Lights poetry books — would “Howl” be “Howl” in a different format?

My father once changed my life by handing me a small green hardbound book with a black square on the cover, where an Art Deco runner bore a torch — a Modern Library edition of “Crime and Punishment.” That murky green became analogous with Raskolnikov’s crime and his suffering, the black square with the policeman who patiently tracks him down. I trace a direct line from that innocuous green volume to my later choice of profession and all that has befallen me since, as if it were the pine cone from which the seed of myself had fallen.

This is what it means to be a book lover. Books speak to us; they are something more than simply a conveyance of information. When my mother, a real book lover, could no longer read, I cleared most of her books from her assisted-living bookcase — the better to replace them with the art books she could still enjoy. But her outrage could not be contained. “Where are my books?” she shouted. “These are books, Mom,” I’d said, defensively. “MY books,” she replied. “I want MY books.” As her daughter, I knew exactly what she meant.

Janet Fitch is the author of the novels “White Oleander,” “Paint it Black” and “The Revolution of Marina M.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.