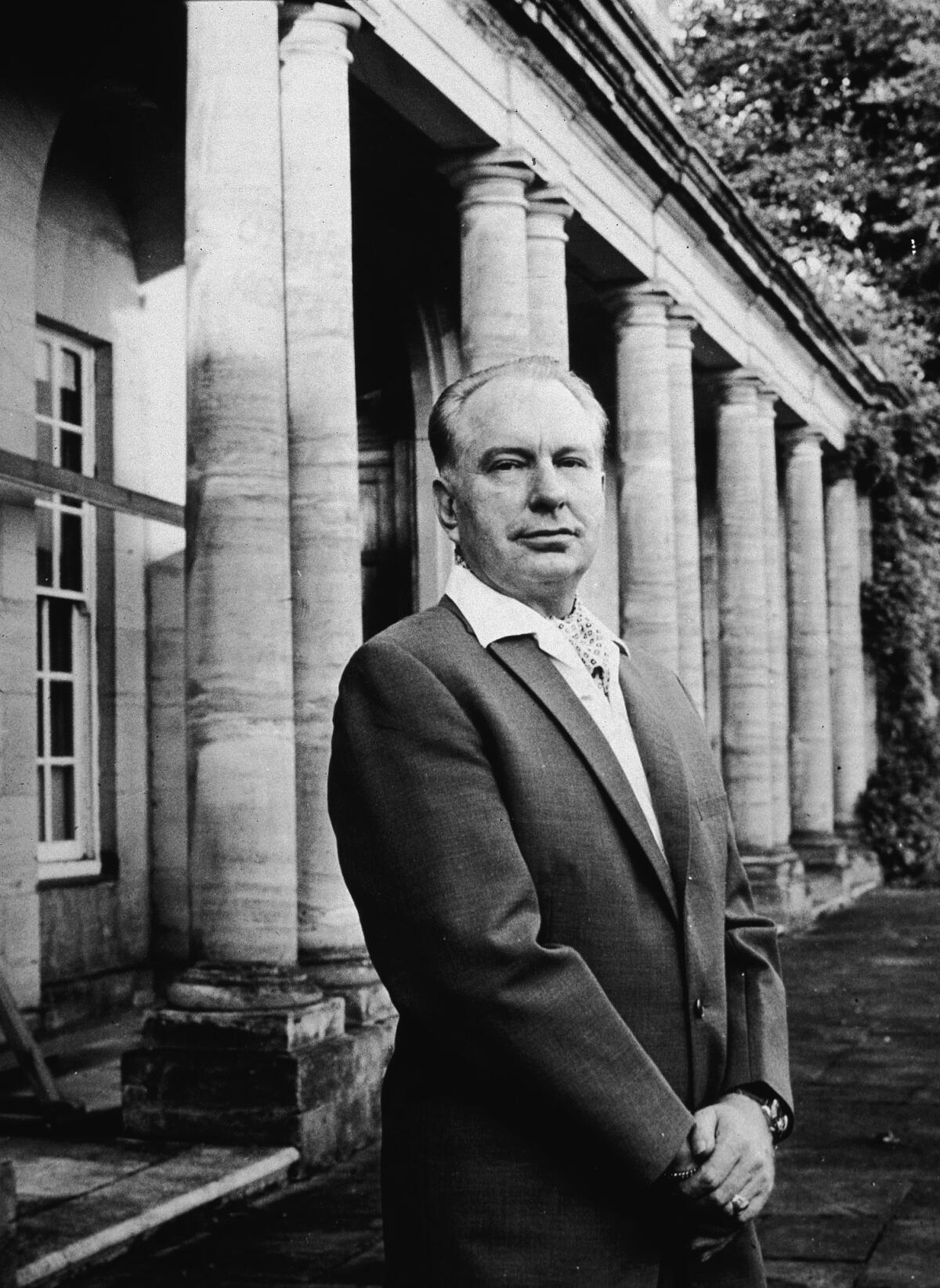

John W. Campbell, a chief architect of science fiction’s Golden Age, was as brilliant as he was problematic

Back in the so-called Golden Age of Science Fiction, the future looked bigger, brighter and more ferocious than it ever would again.

This was from roughly the mid-’30s to the early ’50s, when lean, handsome star-warriors — such as those leading the charge in Jack Williamson’s “Legion of Space” series — could traverse a multi-light-year-sized nebula after only a few hours of heavy turbulence, so long as they turned up the “generators” and tweaked those darn “geodynes” just right. In Robert A. Heinlein’s “Universe,” a city-sized spaceship might travel for many thousands of years until its multi-generational inhabitants forgot they were even riding in a spaceship at all.

And in “Twilight,” by John W. Campbell (a.k.a. Don A. Stuart), a near-future space pilot test-flew himself 7 million years into the future only to find a dying sun, a cold Earth and a dwindling, incurious race of “little misshapen men with huge heads.” While the heads might contain large brains, they didn’t accomplish much thinking. That’s because the unstoppable, self-repairing machines that presided over their mostly deserted cities did all the thinking for them.

These stories were written, or published and conceived into existence, by the undoubtedly great and incomprehensibly peculiar John W. Campbell Jr., who single-handedly designed many of the ways we saw the future then and continue to see it now. Born in Newark, N.J., in 1910, he was raised by combative parents who embodied the extremes of their son’s divided personality: his father, an engineer with Bell Telephone, stressed rationality, planning and control over emotions, while his mother was a wild, tantrum-prone woman who couldn’t be controlled so much as fought “to a draw.” After their divorce, Campbell grew up, like many writers, unhappy, lonely and distressed; he often felt like a disappointment to his father, and his mother’s unpredictable cruelties instilled in him a deep sense of panic about a world that couldn’t be adequately rationalized or controlled.

Often, for a joke, Campbell’s mother and her twin sister assumed each other’s identities to greet him when he returned from school, contributing to Campbell’s lifetime suspicion of anybody who wasn’t himself. This eventually led to one of his finest stories, “Who Goes There?,” in which a shape-shifting alien serially devours scientific researchers in the Antarctic, then assumes their identities in order to trap the next meal. Filmed three times, initially as “The Thing from Another World” (1951, one of my favorite black and white sci-fi films) and later remade as “The Thing” by John Carpenter (1982) and Matthijs van Heijningen (2011), these popular permutations left Campbell’s clearly distinct footprint on modern culture.

But his larger influences go far wider and deeper.

While studying physics at MIT (he was asked to leave after one semester) and later Duke University (where he eked out mediocre grades), Campbell enjoyed his only early success pounding out space operas for the pulps, where he soon established himself as second in popularity to the master of “Gosh, Wow!” intergalactic mayhem, E. E. “Doc” Smith. (Notably, the “Doc” referred to Smith’s PhD in food engineering and not to any form of rocket science.)

Campbell’s early stories remain almost uniformly risible, focusing on problem-solving space adventurers who sit around exchanging endless expository dialogue such as: “ ‘You should talk!’ Russ Spencer laughed. ‘One of the features of that ship is the new Carlisle air rectifiers, guaranteed to maintain exactly the right temperature, ion, oxygen, and ozone content as well as humidity control.’ ”

These early efforts might have sufficiently entertained the already-acclimatized buffs, but they never measured up to good fiction, and it wasn’t until Campbell married a woman with her own literary savvy, Doña Louise Stewart Stebbins, that he developed gravity. Renaming himself in her honor as Don A. Stuart, he began producing poetic, reflective stories that deserve to be remembered — “Twilight,” “Night,” “Forgetfulness” and “Cloak of Aesir” — stories that testify to a young author’s sense of isolation and helplessness in the face of immeasurable universal forces.

Despite an aimless early life, Campbell eventually stumbled onto the job he was born to do — long before anybody realized it was a job worth doing. Until Campbell came along, the pulps were edited by company men who felt little if any personal affection for the stories they published. But in 1937, when Campbell accepted the editor’s chair at Astounding Stories (which he quickly renamed Astounding Science Fiction), he became the first SF fan to shape the genre he loved; and almost immediately he discovered that exploring futuristic ideas for his stories was not nearly so pleasurable as passing those ideas onto others. “When I was a writer,” he told his youthful discovery, Isaac Asimov, “I could only write one story at a time. Now I can write fifty stories at a time.”

Campbell was an industrious conversationalist who loved nothing more than enticing his writers to follow in his own imaginative footsteps; and when he couldn’t entice them, he did what any good pulp editor worth his salt did — he commissioned them. He seemed to enjoy watching them do what he imagined in ways entirely different from how he might have written himself.

Campbell had plenty of ideas to go around and a good eye for the best writers to develop them. Over the next decade, he industriously discovered and/or employed the most influential sci-fi writers of the modern era: Theodore Sturgeon, Lester del Rey, A.E. Van Vogt (for my money, the strangest of them all), Henry Kuttner, Robert Silverberg and L. Sprague de Camp; significant female writers such as Leigh Brackett and C.L. Moore; and ultimately the three most important writers who helped him shape the “Golden Age”: Robert A. Heinlein, Asimov and L. Ron Hubbard.

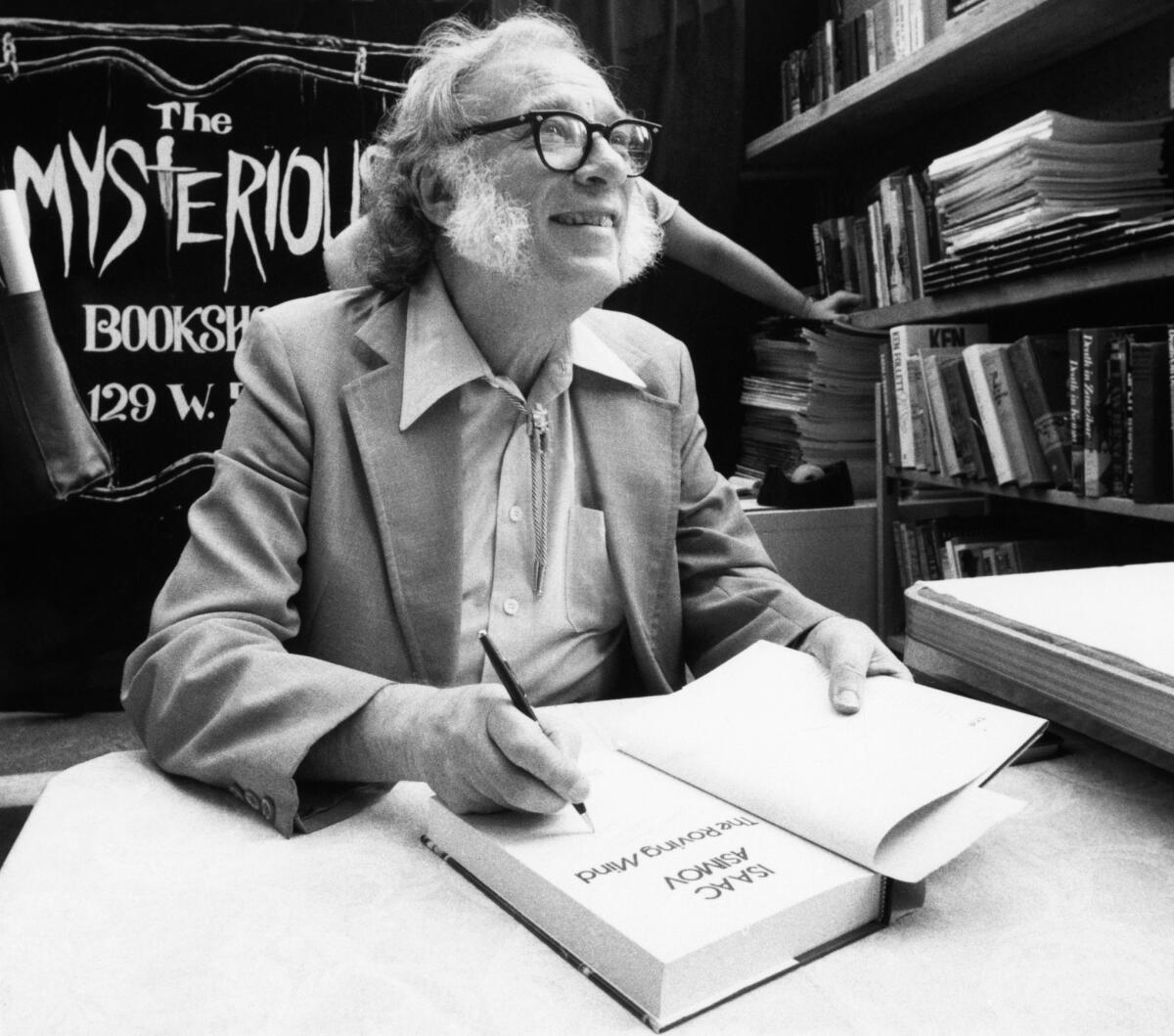

Over a mere few years, Campbell provided Heinlein enough support to make him one of sci-fi’s most stylish practitioners of ideas and gave Hubbard free rein to produce numerous popular and still readable fantasies, notably “Fear” and “Slaves of Sleep.” He guided the young Asimov — a poor Russian-Jewish immigrant who grew up reading Astounding while working in his father’s newspaper shop — into writing his most famous works, such as the unforgettable novelette, “Nightfall,” about an alien race who only glimpse the stars one night every thousand years and then go mad, and a series of “Foundation” novels describing the efforts of psycho-historians to shape the future history of their galaxy.

It was a multiple match made, if not in heaven, in outer space; and in his enjoyable, cinematically-absorbing history of Campbell and his magazines, “Astounding,” author Alec Nevala-Lee affectionately charts the course of all these contradictory talents, energies and ambitions.

Campbell’s imaginative life often revolved around the desire to maintain emotional order in an emotionally disordered world. And at the heart of his personal metaphysic lay a desire to extol the virtues of a type that he presumed himself to be — the “competent man,” as exemplified by the firm-but-kind father figures in Heinlein’s best novels and stories. Unlike the qualified, limited-ability academics who spurned him at Duke and MIT, the “competent man” knows a little bit about everything, such as how to “change a diaper, plan an invasion, butcher a hog, conn a ship, design a building, write a sonnet, balance accounts, build a wall, set a bone, comfort the dying, take orders, give orders, cooperate, act alone, solve equations, analyze a new problem, pitch manure, program a computer, cook a tasty meal, fight efficiently, die gallantly. Specialization is for insects.”

Campbell and his favorite writers certainly never saw themselves as insects.

The trajectory of all four men describes a similar sudden rise and sad demise. First, a burst of explosive creative energy in the 1940s. Then a withdrawal from the genre that fed them in the ’50s; and finally, a series of strangely unpredictable final acts and departures in the ’70s and ’80s.

Campbell, who had often celebrated the joyous promises of “atomic energy,” was so shocked by its Hiroshima blossoming that he spent most of his postwar life seeking ways to control the human emotions that unleashed it. As a “competent man” who believed in self-made remedies, he quickly became one of Hubbard’s earliest champions; eventually, he not only announced the new “science” of Dianetics in Astounding, but became one of its most devoted patients, believing Hubbard could “audit” out his many deep-seated emotional traumas from as far back as the fetal state. “I firmly believe this technique can cure cancer,” he wrote Heinlein in 1949. And he did firmly believe it — for a while.

After he stopped believing in Hubbard and his Dianetics, Campbell went digging for other basement-built theories of human and social improvement, eventually turning Astounding (later renamed Analog) into a cross between Popular Mechanics and a crash-course in miracle-peddling. He grew enamored of concepts such as dowsing, astrology and telekinesis, which he referred to as “psionics.” At one point, impressed by Hubbard’s “E-meter” machine, described by Nevala-Lee as “a metal box hooked up to two tin cans,” and another inventor’s so-called “psionic machine” that sounded like a 6-year old’s art project glued together with random electrical components and colored string, he decided to “invent” a device of his own. The resulting “Campbell Machine” added up to a “meaningless switch and a pilot light on the outside of the box” and “a circuit diagram with ink,” and a few other curlicues stapled here and there. He seemed proud of it; but it was never clear what “it” was or what “it” was supposed to do.

Astounding/Analog went downhill, and so did Campbell. He developed into an angry old man who drank and smoked too much at sci-fi conventions and collared anyone still impressed by his reputation to talk at them until they weren’t impressed anymore. While Heinlein and Asimov enjoyed their late years as bestselling novelists and cultural celebrities, Campbell’s audience grew smaller, just as the theories he expounded grew nastier. He argued that tobacco might prevent cancer, that “Negroes lack self-discipline” and that homosexuality was a sign of cultural decline. He decried the murdered demonstrators at Kent State and once said, “I’m not interested in victims,” as if he were pronouncing an irrefutable mathematical theorem. “I’m interested in heroes.” Like many men defeated late by their own ambitions, Campbell didn’t respect striving individuals like himself; he only respected super-versions that never existed. Subsiding bitterly into self-dissatisfaction, he went from being one of America’s most prescient futurists to one of its ugliest reactionaries.

So it was probably a form of salvation that Campbell died at 61, when his greatest achievements could still be remembered relatively free from his later perorations. Nobody put it better than Laurence Janifer, who remarked after Campbell’s death: “The field has lost its conscience, its center, the man for whom we were all writing. Now there’s no one to get mad at us any more.” But equally correct was Michael Moorcock, who succeeded Campbell as science fiction’s next great sci-fi editor at New Worlds in the ’60s, when he labeled Analog “a crypto-fascist deeply philistine magazine.”

They were both right; just as they were both raised in the monumental and inescapable shadows of Astounding.

Bradfield is the author of a dozen books, including the recent novel “Dazzle Resplendent: Adventures of a Misanthropic Dog.”

Alec Nevala-Lee

Dey Street: 544 pp., $28.99

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.