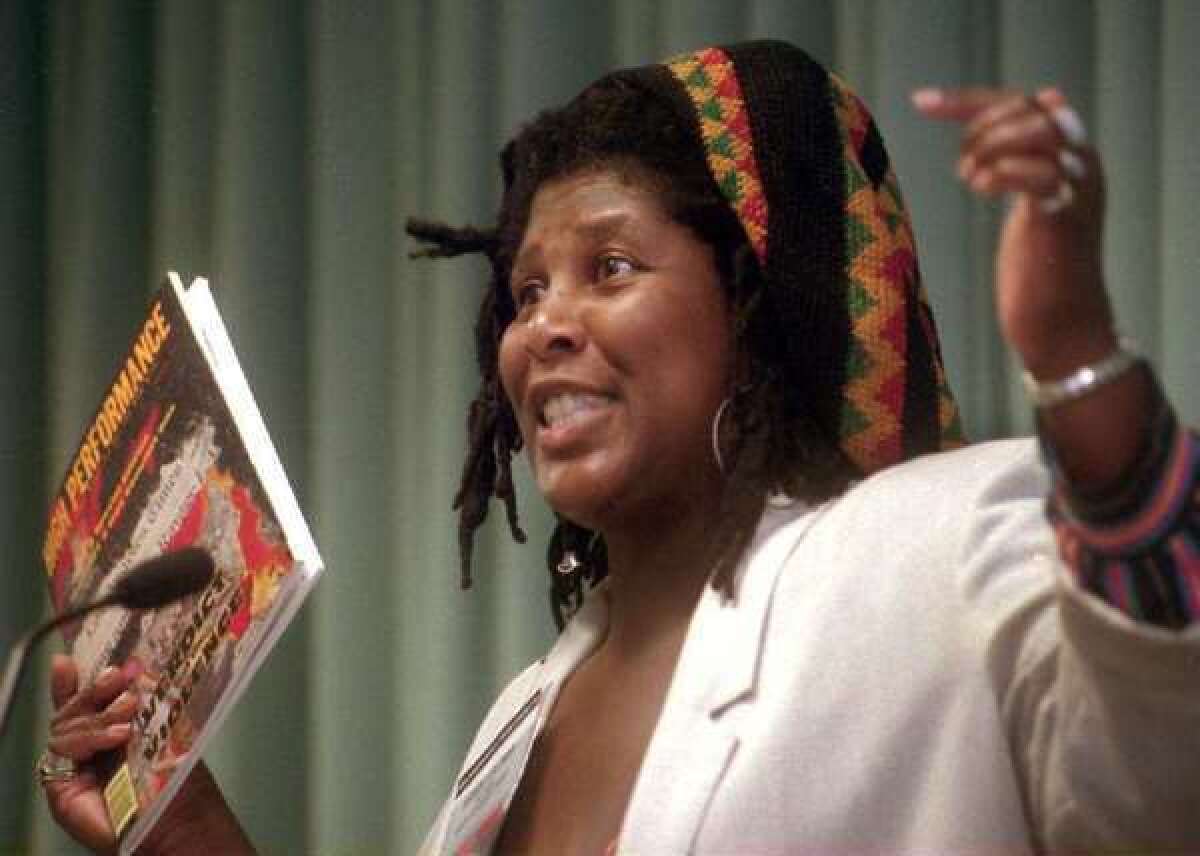

Remembering Wanda Coleman

Wanda Coleman was a force of nature. The last time I saw her, in early 2012, she took over a panel we were on at 826LA. The subject was Los Angeles literature — something Coleman, who died Friday at the age of 67 after a long illness, embodied at the very center of her being — and all of us, her fellow panelists, were more than happy to sit back and listen to her talk. There was that magnificent voice, for one thing: resonant, oratorical, deep with experience. And then, of course, there was everything she had to say.

Coleman was the conscience of the L.A. literary scene — a poet, essayist and fiction writer who helped transform the city’s literature when she emerged in the early 1970s. Born and raised in Watts, she began to write as a young girl, and even then she did not back away from what she felt. “I have a journal that goes back to when I was 11,” she told me in a 1997 interview, “and from the beginning, the pages are virulent with hate.”

That hate had its roots in discrimination, which she experienced on a number of levels at once. “I knew,” she remembered in her astonishing essay “The Riot Inside Me,” “that the second I entered the classroom, I would face the ongoing ridicule garnered by my kinky grade of hair, bright eyes, toothy smile, and dark skin — not from the White students, the few Mexican, Asian American, and Filipino students, or the teacher, but from my Black classmates.”

For Coleman, this led to a vivid bifurcation: She was an outsider who became a force for community. The former helped define her voice, her sensibility, while the latter gave it context, in the process transforming the way Los Angeles wrote (and read) about itself.

When she began to write, as a member of the Watts Writers Workshop that sprang up after the 1965 riots, L.A. literature was largely a literature of exile, produced primarily by those from elsewhere, who lingered briefly along the city’s glittering surfaces and did not invest the place with any depth. Working in the tradition of John Fante, Chester Himes and Charles Bukowski, Coleman invented a new way of thinking about the city: street-level, gritty, engaged with it not as a mythic landscape, but in the most fundamental sense as home.

Home, of course, is a complex concept, and even as she embraced Los Angeles, Coleman fought back against it also, outraged by its inequities, its failed promises, its social and racial hierarchies.

“The nature of the community I matured in was extremely tentative and vulnerable to constant shifts in the sociopolitical sand,” she observed in her 1996 book “Native in a Strange Land.” “If there were traditions; institutions and first families, I was unaware of them. The past was a rumor, the present a trial, and the future an improbability.”

Faced with such an uncertain landscape, Coleman did what she had to do: She invented herself. By the time her first poetry collection “Mad Dog Black Lady,” came out in 1979, she’d spent a year as a writer on “Days of Our Lives,” winning a daytime Emmy; later, in the 1990s, she’d write a column for the Los Angeles Times Magazine.

Through it all, she was, not unlike the city she embodied, “defined by the dense traffic of intersecting ideas and ambitions, the complex territorial collisions between fact and feeling, consumerism and culture, the pragmatic and the profound.”

Coleman could be confrontational, and she was certainly uncompromising, a label, she found “quite pleasing” when applied to her work. At the same time, she was often tender, and always aware of, and working from, her own vulnerability. “usta be young usta be gifted — still black,” she wrote in “American Sonnet 35,” paying ironic tribute to both Aretha Franklin and herself.

The prose poem “Angel Baby Blues” addressed a similar weariness, albeit from a different angle: “something keeps telling me i need to leave Los Angeles and i say i would if’n i could maybe it’s smog addiction maybe it’s ambition maybe it’s civic pride maybe all of that maybe it’s the other something telling me i’m gonna make it if i hang on long enough strong enough i’m going to make it or break it (lose me lose your good thang) and it’s breakin’ me not makin’ it.”

Coleman was widely regarded as the unofficial poet laureate of Los Angeles; her 2001 collection “Mercurochrome” was a finalist for the National Book Award, and in 2012, she won the Poetry Society of America’s Shelley Memorial Award.

More important, she was the keystone, the writer who shifted L.A. writing, irrevocably and to the benefit of all of us, from an outside to an inside game, a literature of place.

The importance of this can’t be overstated; without Coleman, there’d be a lot less here for the rest of us. She taught us to write about the city we saw, the city in which we lived, to turn our backs on the stereotype and stare down the reality instead.

The point is a kind of freedom, by which we learn something essential about ourselves. “we were never caught,” she opens “In That Other Fantasy Where We Live Forever” — a riff on the recklessness of youth that somehow also suggests a more lasting transcendence.

Today, though, I find myself thinking more about the final stanza of that poem: “when you split you took all the wisdom / and left me the worry.”

ALSO:

Emily Dickinson’s handwritten poems as art

Wanda Coleman, acclaimed L.A. poet, has died at 67

Wanda Coleman dies at 67; L.A.’s unofficial poet laureate

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.