Some notes on the National Book Awards

On Wednesday night, the National Book Awards were presented at a black-tie dinner at Cipriani Wall Street in Manhattan. “The Oscars of the Book World,” host Mika Brzezinski called it, although, as Fran Lebowitz once sniffed, “It’s the Oscars without money.”

Brzezinski and Lebowitz represent what we might call the two opposing poles of the National Book Awards: celebrity and literature. Over the last decade or so — since a celebrated dust-up over the 2004 fiction finalists, only one of which had sold more than 2,000 copies — the National Book Foundation, which administers the prizes, has made a concerted effort to make them more high profile, more accessible, more fun.

Don’t get me wrong: I’m not suggesting that this has dumbed down the National Book Awards; just the contrary, in fact. In recent years, winners have included Patti Smith, Richard Powers, Denis Johnson, Sherman Alexie, William T. Vollmann — some of the most powerful writers we have.

And yet, I have my doubts about the glamour of the event, the formal attire, the TV commentator as host. Is this really what literature has come to, that we need to play up to a culture that clearly has little use for us, that we should embrace all the orthodoxies of class, of commerciality, that writing, at its most incisive, stands against?

Take James McBride, journalist and jazz musician turned novelist, who won the fiction award for his novel “The Good Lord Bird.” In this book, a young slave rides with John Brown while passing as a girl, a vivid statement on the hierarchies by which we define ourselves.

Wednesday night, McBride was, as he often is, sharply funny, noting that the book had offered solace during a rough period in his life, marked by his divorce and the death of his mother. “It was always nice,” he said, “to have somebody whose world I could just fall into and follow him around.”

McBride wasn’t the only winner to write out of a sense of social conscience; George Packer, who took the nonfiction prize for “The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New America,” reports on the dislocation of an America that will never set foot inside a place such as Cipriani, an America of economic uncertainty and decline.

Los Angeles writer Cynthia Kadohata’s “The Thing About Luck,” which won for Young People’s Literature, traces the generational struggle between a Japanese American girl and her grandparents as they work through harvest season; it is a book that, in every way that matters, explores what it means to be American.

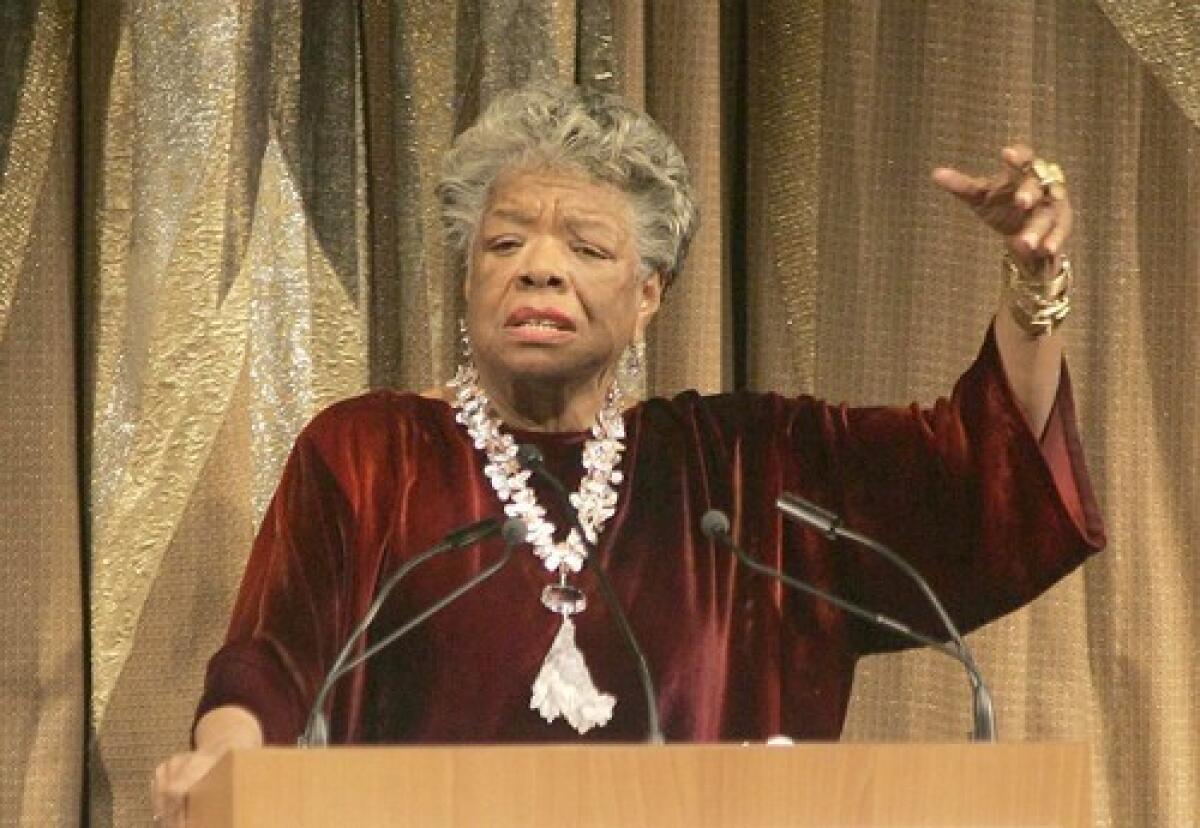

Perhaps nowhere was this as elegantly represented as by Maya Angelou, who sang onstage in her wheelchair while accepting the Literarian Award for Outstanding Service to the American Literary Community. “Easy reading,” Angelou said, “ is damn hard writing” — an article of faith for anyone who has ever tried to express him or herself by the written word.

What Angelou is saying is that it is an almost insurrectionary gesture to write honestly, to sit down, day after day, and try to get at the depth of experience, of feeling, to strip away the platitudes and come-ons by which we are encouraged to forget ourselves. Think about her books and how they never flinch, finding beauty not in the degradations they describe but in her ability to overcome.

This is what was celebrated Wednesday, not the glitz of a black-tie dinner but the substance of the art.

Or, as Angelou put it, “I’ve been trying to tell the truth as far as I know it” — words to live by, whether or not you write.

ALSO:

Who should win the National Book Awards?

National Book Awards go to James McBride, George Packer

Alice Munro’s quiet, precise works lead to Nobel Prize in literature

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.