Following L.A.’s history through maps

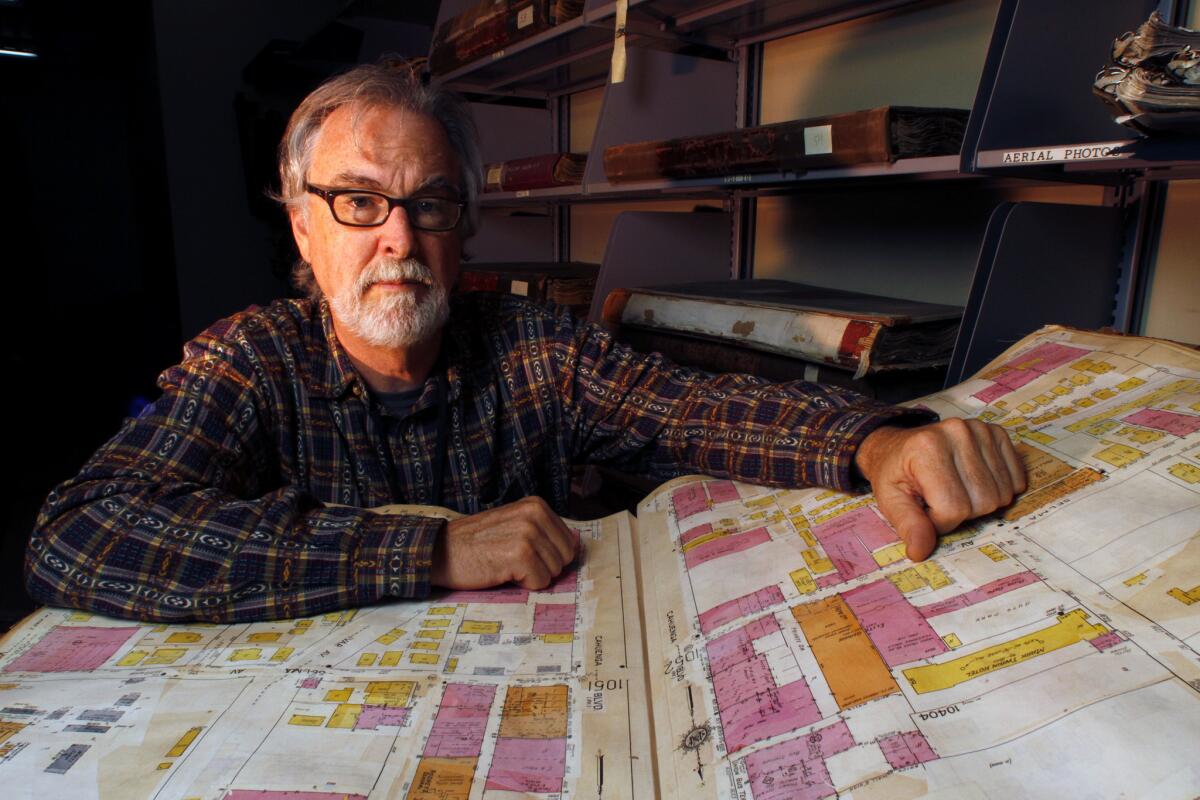

For the last couple of years, Los Angeles Public Library map librarian Glen Creason has been involved in one of the most interesting literary projects in Southern California: to write each week, on the Citythink blog of Los Angeles magazine, about a map from the library’s collection. The idea is to excavate the hidden history of the city, an endeavor with which I have an abiding sympathy.

Part of the reason L.A. continues to confound so many of us, after all, is its complicated relationship with its past. The history is right there, on the surface, and yet we don’t see it, not really, even now.

Every six months or so, I take a group of graduate students on a walking tour through part of downtown, starting at California Plaza, at the top of Bunker Hill, and finishing in Little Tokyo, at the site of the Asuza Street Revival, where the American Pentecostal movement essentially began. A dozen blocks maybe, and yet in it, you can see the story of Los Angeles, if you know where to look.

Creason knows where to look: His 2010 book “Los Angeles in Maps” offers a lavish set of panoramas, framing the city as a series of slices, points of view. As it happens, his most recent Citythink post zeroes in on the very neighborhood where I conclude my walking tour: Little Tokyo and Azusa Street.

What interests him is not the community’s Japanese roots so much as its African American heritage, which goes back to Biddy Mason, a former slave turned midwife who, in the late 19th century, became one of Los Angeles’ earliest black landowners.

“Later,” Creason writes, “she would buy land along Azusa Street … while selling to other black families, thus creating the first all-black street in L.A.”

The Azusa Street Revival is fascinating for all sorts of reasons, not least for what it suggests about Los Angeles’ racial heritage. “[A]ll races were invited and accepted” to participate in services, Creason tells us, which highlights something of the flavor of the community.

We like to think of ethnic enclaves (Chinatown, Little Tokyo) as enclosed, insular, bastions of identity against the outside world. While that is true to an extent — especially in L.A., where restrictive housing covenants kept African Americans in particular from buying property in certain neighborhoods — there was also more interaction, more overlap, than we might commonly suppose.

In his serial novel “The Tale of Osato,” published in the Japanese language daily Rafu Shimpo in 1925 and 1926, Shosun Nagahara portrays a fluid city, in which his immigrant characters cross paths with Anglos, blacks, Chinese — the full panoply of an expanding metropolis. The pressure of these engagements ultimately helped, in many ways, to break down the rigid boundaries of Los Angeles’ racial heritage.

Creason describes another side of this fluidity in his account of Little Tokyo, recalling the African American families who “reluctantly seized the opportunity to settle down” in the neighborhood after relocation effectively rendered it a ghost town.

“Despite the terrible conditions,” he writes, “progress was made: A non-discriminatory job market, actions by the local authorities, and small advances in civil rights carried the new black community forward, and the old Miyako Hotel at 1st and San Pedro … became the Civic Hotel, where legendary jazz saxophonist Charlie ‘Bird’ Parker stayed.”

Equally important, after the war was over, the community stood in “solidarity with the oppressed Japanese minority and did not fight their return to Little Tokyo.”

It’s a lot to get from a map, but then, that is the whole idea of Creason’s project, that the story of the city is revealed between the lines.

This is true anywhere, I suppose, but particularly here, where history remains if not elusive than often at arm’s length, the sort of thing you have to look for, which makes these maps — and their explication — a set of portals, points of entry, through which the present is necessarily infiltrated by the past.

Twitter: @davidulin

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.