Discovering the screenplay of Joan Didion’s ‘Play It As It Lays’

Joan Didion in 2005 at her apartment in New York.

Recently, I bought a copy of a 1972 anthology called “Works in Progress” that includes what appears to be the only published screenwriting by Joan Didion and John Gregory Dunne. The sample in question features the first 44 pages of “Play It As It Lays,” the 1972 film based on Didion’s novel of the same name.

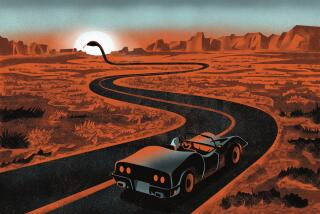

Starring Tuesday Weld and Anthony Perkins, “Play It As It Lays” offers a scathing portrait of Hollywood through the perspective of Maria Wyeth, an actress who is coming undone. Like the novel, it unfolds in fragments, mirroring the disassociation of the character, who spends great blocks of time traversing L.A.’s freeways, as if looking for a structure or a meaning on which to hang her life.

“She drove the San Diego to the Harbor,” Didion writes early in the novel, “the Harbor up to the Hollywood, the Hollywood to the Golden State, the Santa Monica, the Santa Ana, the Pasadena, the Ventura. She drove it as a riverman runs a river, every day more attuned to its currents, its deceptions, and just as a riverman feels the pull of the rapids in the lull between sleeping and waking, so Maria lay at night in the still of Beverly Hills and saw the great signs soar overhead at seventy miles an hour, Normandie 1/4 Vermont 3/4 Harbor Fwy 1.”

The screenplay captures much of this jangly disconnection, the lack of narrative connection that has long been Didion’s most vivid theme. Maria is adrift, not only on the freeways but also in her life, which involves an abortion and a failing marriage, as well as a young daughter who has been institutionalized.

“I was experimenting,” her husband, Carter, explains, describing an early cinéma vérité project in which Maria talks, as herself, about her own history. “I was trying to see how far I could break down the barrier between film and real. … That’s the whole point of the film. It was not a performance.”

The same might be said about the character, who is also trying to break down some sort of barrier, between how she is expected to behave and how she really is. If the novel evokes this through the use of close third-person writing, the screenplay takes a more directly personal approach.

Maria is in every scene, isolated, haunted by images: those freeway signs, for one thing, and the lingering echoes of her abortion, which ends the “Works in Progress” sample with a stunning example of compression: “SIX FAST CUTS INSIDE THE HOUSE,” Didion and Dunne write, “the DOCTOR’S line jacket,” “a chrome kitchen garbage container,” “a faucet being turned on.”

Film, of course, is a visual medium, although it is driven (how can it not be?) by words. The impressionistic aspect of this scene, of the entire script, reminds us of the weight a small detail, a gesture or a movement, can contain.

In that sense, the “Play It As It Lays” screenplay may best be read as a distillation of the novel, streamlined, although it is also writerly on its own terms. This is no sketch, in other words, but a fully rendered piece of dramatic work.

To watch the movie, as I did over the weekend, is to be struck by how closely the finished product follows the script. It is as if we are engaging with a play, something with intention, which makes me wonder why this material have never been collected, why there is no volume of Didion and Dunne’s writing for the screen.

@davidulin

MORE FROM BOOKS:

Get ready to be obsessed by these 29 page-turners

27 nonfiction books you’ll want to read -- and share -- this summer

Listen up: Here are 11 audiobooks you’ll want to ‘read’ this summer

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.