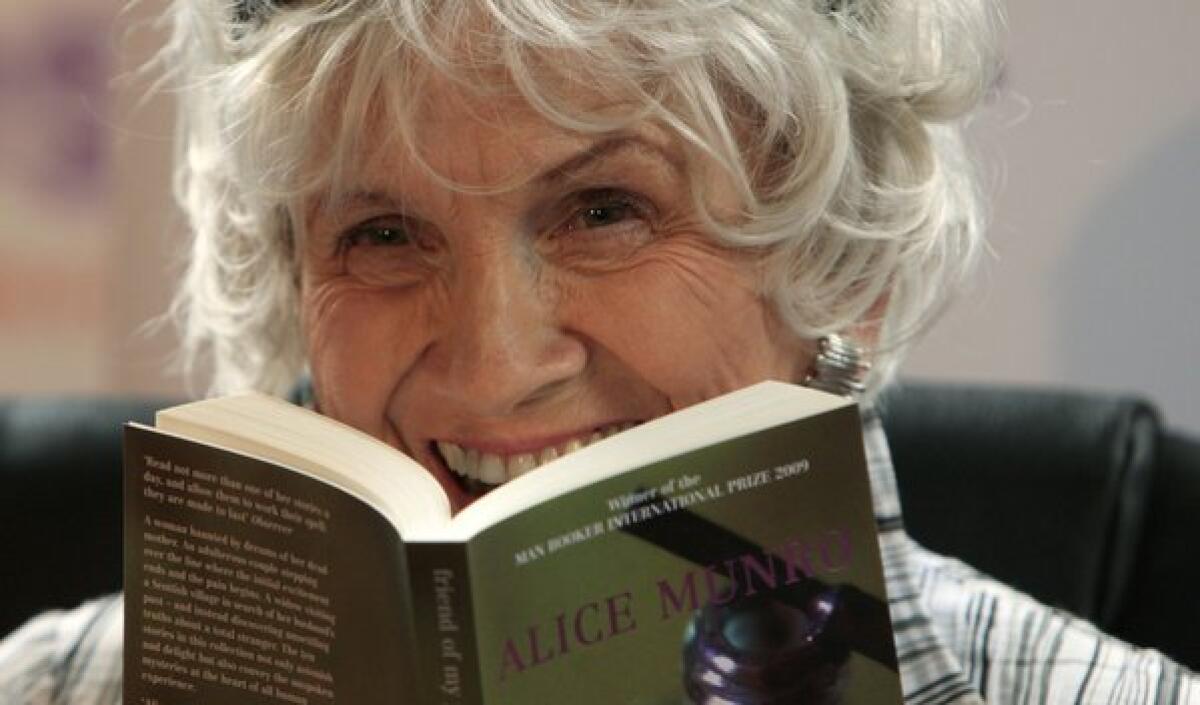

Alice Munro, reviewed by L.A. Times: ‘casually impeccable,’ ‘genius’

Alice Munro, who won the Nobel Prize in Literature on Thursday, lives a quiet life in a small town in Ontario, Canada. When the Los Angeles Times’ Susan Salter Reynolds visited her in 2006, she explained that she was a “weird” teenager. “I was already deep into being a writer. I went to a dance. Nobody danced with me. This bewildered and annoyed me. I never went to a dance again.”

Instead of going to dances, Munro honed her craft, publishing more than a dozen books, most collections of short fiction. In her five decades of publishing, here’s a selection of what Times reviewers had to say about some of her work.

“Dear Life” (2012) is full of “casually impeccable stories,” wrote Charlie McNulty. “Munro has a genius, no empty word here, for selecting details that keep unfolding in the reader’s mind.... How does Munro manage such great effects on a relatively small canvas? It’s a question that most anyone who has seriously attempted to write a short story in the last 20 years has pondered. This collection hints at answers, with its banishing of certainties and calm acceptance of the not unusual overlap of love and cruelty -- the way, say, a father accustomed to using a razor strap could find just the right comforting words during his young daughter’s bout with insomnia.”

The 2009 collection “Too Much Happiness” suggests that the “greatest work of fiction...is the construction of a shared social life to serve as a comforting bulwark against the dangerous contingency of the world,” wrote Troy Jollimore. “So much short fiction shies away from this complexity, presenting a pared-down vision of reality, stripped to what the author sees as life’s essential principles. Munro’s stories, by contrast, remind us that the non-essential things -- the things that didn’t have to happen, that could have been avoided if people were a bit more rational, or a bit more careful, or if the world just made a bit more sense -- so often determine the shape of a life. In doing so, they remind us that comfort and security are by their very nature essentially fragile and ephemeral, if not largely illusory.”

How are her stories put together? Reviewing her 2004 collection “Runaway Stories,” Michael Frank explained: “ Munro jumbles time and occasionally tense with expertise; she is unafraid of length; she sometimes embraces symbols that in a lesser writer’s work would be hackneyed or arch; she makes deft use of nature and landscape to set a story’s mood or suggest a character’s frame of mind; she always stretches for the fresh turn of phrase, the unexpected piece of dialogue, an image or a comparison that distills a person (or a moment) just so. Now and then a whiff of coldness settles over the proceedings, a rigorous, almost clinical detachment, not only in the characters’ behavior (especially in the way daughters regard their parents and relations) but in the narrator’s assessment of it. There is not a speck of sentimentality in Munro’s fictional world, ever.”

Munro writes “with a grasp of craft and a profound sense of human contradiction,” in “The Progress of Love” (1986). What she does, wrote Art Seidenbaum, “is travel around inside the skins of people who react to real problems in not-so expectable ways.”

Our first review of Munro’s work, in 1974 of her second collection, “Something I’ve been Meaning To Tell You,” captured what would become her specialty. “Munro brings out startling nuances of the mind and heart,” wrote Tom Nolan, “and charts a whole geometry of emotion involving the tactical kindness, the hatred hidden and watchful, the abiding superstition, the surprising manifestation of love, and the brief precious clarifying instant when a truth is revealed.”

ALSO:

American adults have low (and declining) reading proficiency

Writer Ilija Trojanov on being unexpectedly barred from the U.S.

Inside the legendary Gay Talese story ‘Frank Sinatra Has a Cold’

Carolyn Kellogg: Join me on Twitter, Facebook and Google+

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.