Kareem Abdul-Jabbar memorializes the great John Wooden in ‘Coach Wooden and Me’

Basketball legend and author Kareem Abdul-Jabbar discussed politics, sports and his role in community activism with L.A. Times editor-in-chief Davan Maharaj at the Festival of Books on Saturday.

Lew Alcindor had his pick of colleges as a senior at Power Memorial Academy in New York in 1965. One of the most sought-after high school basketball players in history wanted a school where students were respected, where his growing sense of social activism could be nourished and, of course, a place where his already vast skills on the court could be refined and taken to a singular level.

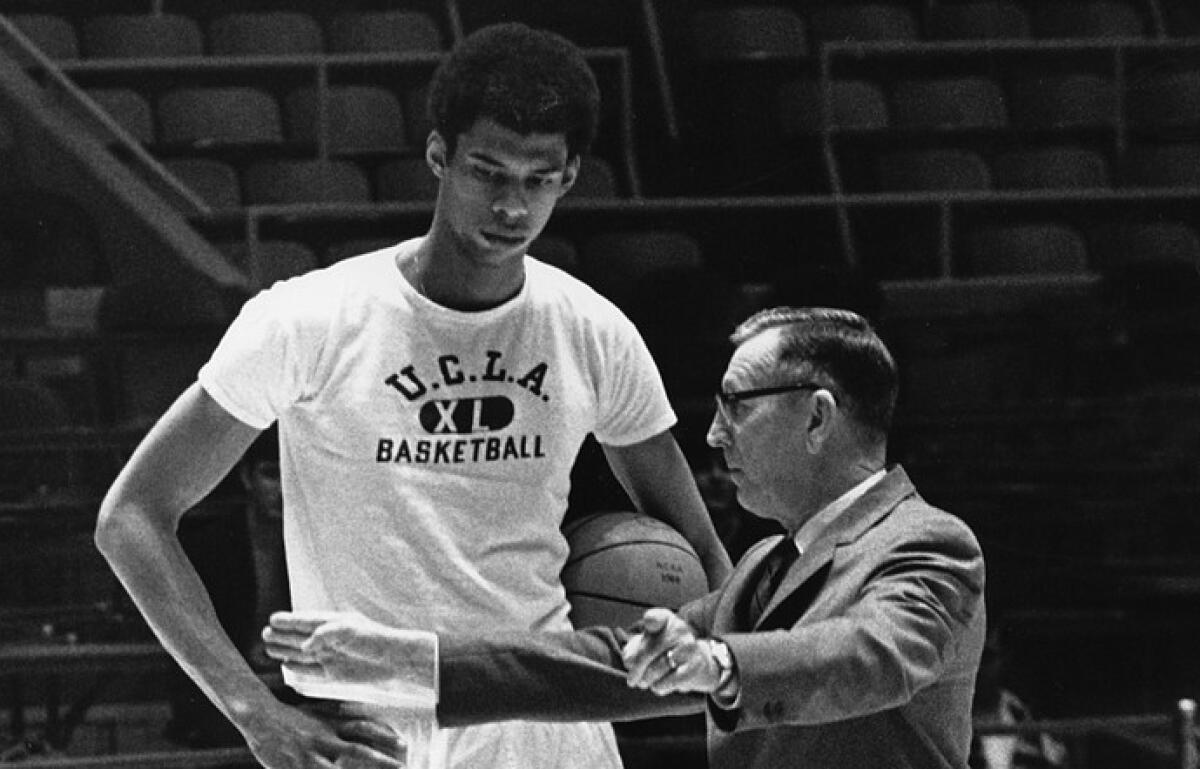

He decided that UCLA and, particularly, coach John Wooden were the right fit. His relationship with Wooden, the most successful college basketball coach in history, became almost life-defining for the young student who would convert to Orthodox Islam in 1968 and change his name to Kareem Abdul-Jabbar in 1971. It became a guiding force, far deeper than he ever could have imagined as a self-described cocky kid from the big city who had headed West to find himself and play a little hoops — and who would go on to become the leading scorer in the history of the National Basketball Assn.

Abdul-Jabbar candidly chronicles the evolution of their relationship in “Coach Wooden and Me,” an examination of the life lessons Wooden consistently preached. Part nostalgia, the book is also a reckoning by Abdul-Jabbar of the racism he faced as a young athlete during the tumultuous civil rights era, of how he and Wooden dealt with that racism and of Abdul-Jabbar’s realization much later in his life of the effects he had on Wooden’s beliefs and of the ways Wooden had supported him.

“This book is not just an appreciation of our friendship or an acknowledgment of Coach Wooden’s deep influence on my life,” Abdul-Jabbar writes. “It is the realization that some lives are so extraordinary and touch so many people that their story must be told to generations to come so those values aren’t diminished or lost altogether.”

Their relationship evolved over nearly half a century. It began as a mostly straightforward coach-player dynamic at UCLA. It became a bit deeper during Abdul-Jabbar’s NBA years with the Milwaukee Bucks, though it still focused largely on basketball. Then it blossomed after he returned to Los Angeles to complete his NBA career with the Lakers, as the two dined together frequently, consoled each other through the deaths of family members and friends and spent relaxing hours in Wooden’s small, cramped den watching sports or western movies, arguing about baseball teams and reveling in each other’s company, as close friends do.

“I could feel the difference whenever I went to sit with him in his den,” Abdul-Jabbar wrote of the latter stage of the relationship. “Before, it had felt like I was visiting a friend. Now it felt like I was coming home.”

Although it was clear that Abdul-Jabbar had an impact on Wooden’s life, Wooden remained his valued teacher and emotional guide until the former coach’s death at 99 in 2010.

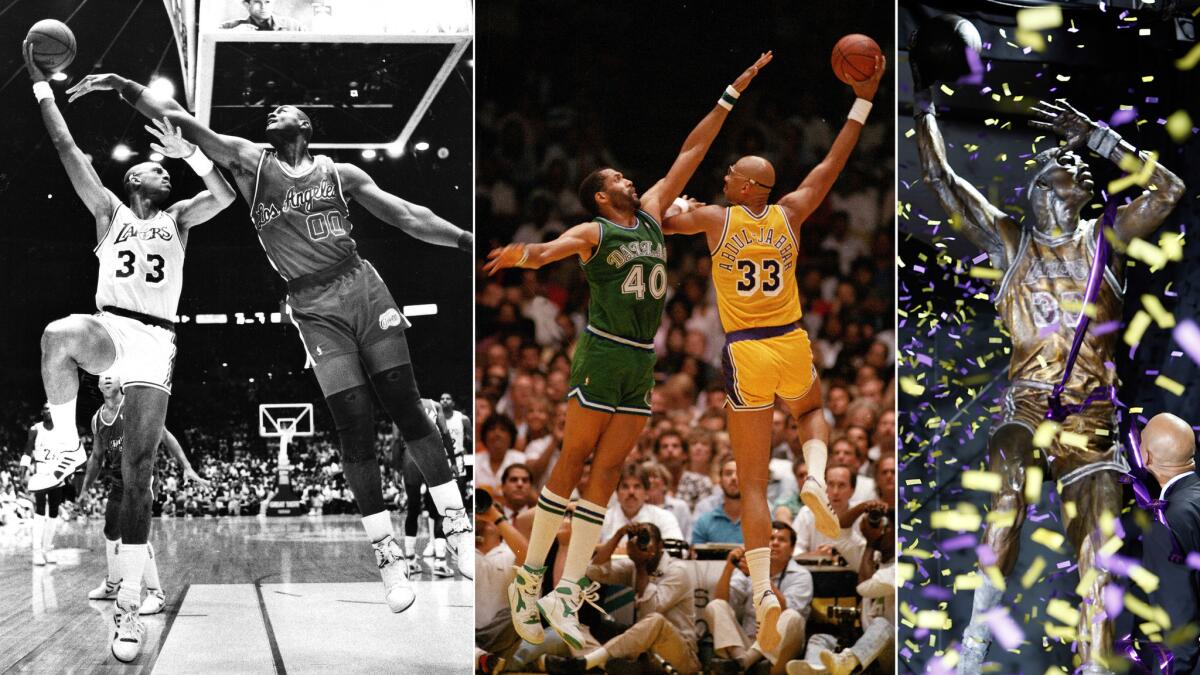

Wooden’s basketball knowledge was the basis of their early relationship, a coach and a player, mutual respect but not much warmth. Wooden worked with Abdul-Jabbar tirelessly to perfect his sky hook, a shot that throughout his career was nearly impossible to defend. He worked his players relentlessly in practice, repeating drill after drill, driving them exceptionally hard. Those lessons reaped huge dividends on the court, where the Bruins won consecutive national championships in Abdul-Jabbar’s three years, the first three of an unmatched seven in a row Wooden would accumulate. At that time, freshmen were not eligible to play on the varsity. His freshman team, though, went undefeated and easily beat the varsity in a scrimmage that opened the new Pauley Pavilion.

“From the first day of my freshman year until the last practice of my senior year, we ran,” Abdul-Jabbar writes. “And then ran some more. There were no shortcuts in John Wooden’s basketball program. You did it until you did it right, and then you did it again. The basic philosophy that I learned on those long afternoons enabled me to extend my professional career to twenty years, longer than any other player.”

Many of the lessons Abdul-Jabbar learned from Wooden were just as relevant long after he had hung up his basketball sneakers. And that’s a common theme in this book: It was often years later that Abdul-Jabbar would realize Wooden’s teachings in a basketball reference actually carried well beyond that.

“Coach Wooden’s philosophy has proven to be a lifelong lesson for me,” he writes. “When I am scheduled to give a speech, I write it, then practice it, then practice it some more. … My opponent is now myself, my inclination toward laziness. The discipline I learned through those conditioning drills has allowed me to face my devious opponent and beat him constantly.”

Abdul-Jabbar entered UCLA at a time of intense racial strife in the United States. Malcolm X had just been assassinated, civil rights marchers in Selma, Ala., had been attacked and beaten by police, the Watts riots erupted. His sensitivity had been heightened in 1962 on a trip to North Carolina where he first developed an understanding of “separate but equal.”

Abdul-Jabbar was frequently the subject of racial epithets from crowds while at UCLA, and he writes of several incidents in which he and Wooden faced racism.

Two experiences were particularly painful for Abdul-Jabbar. He was called the “n-word,” first by another boy he considered his best friend, later when Jack Donahue, his coach at Power Memorial and a man the player considered progressive in his racial views, used the term during a halftime rant in an apparent effort to motivate his young player after a lackluster first half.

“It was because of the fresh scar of Coach Donahue’s betrayal that I kept myself a little aloof from Coach Wooden,” Abdul-Jabbar writes. “I had been trusting once and had my heart broken. I wouldn’t let it happen again. … I would force myself to be wary, especially of older white men pretending to be my friend.”

Abdul-Jabbar was frequently the subject of racial epithets from crowds while at UCLA, and he writes of several incidents in which he and Wooden faced racism.

After dinner together in a restaurant to celebrate the undefeated season of 1966-67, an elderly white woman approached them and asked how tall Abdul-Jabbar was, adding, using a racial epithet, “I’ve never seen a ... that tall.” Also, his sophomore year after a game in Corvallis, Ore., he signed autographs for 30 to 40 kids before he needed to leave, at which point a man used the same racial epithet.

In each instance, Wooden said nothing, though it was clear he was troubled by the remarks and had to restrain his anger against the man at the autograph session, where children were present. But his comments to Abdul-Jabbar afterward were that he believed in the goodness of most people and that he hoped the ignorance of a few wouldn’t change that.

It wasn’t until well after those moments that Abdul-Jabbar learned how much they affected Wooden. Years later he read an interview with Wooden in which he questioned his own philosophy of the goodness of his fellow men.

Abdul-Jabbar quotes Wooden from that interview: “I had no idea how tough it was for him at times. I learned more from Kareem about man’s inhumanity to man than I ever learned anywhere else. … I had never imagined that people could feel or talk like that.” Abdul-Jabbar was moved and a bit shaken. “I felt a deep sadness after reading that,” he writes, “knowing my presence had caused him to doubt his fundamental beliefs.”

As was often the case, Wooden had not confided in Abdul-Jabbar while he was one of his players. There was a great deal of backlash after Abdul-Jabbar decided not to play on the 1968 Olympic basketball team because of racial inequality in this country. One woman criticized him in a letter to Wooden.

It was only after Wooden’s death that Abdul-Jabbar saw a copy of the letter Wooden had written the woman in response, defending his player’s position. Wooden had never mentioned the letter. “Coach Wooden didn’t care about receiving credit. A good deed was its own reward,” Abdul-Jabbar writes. “Coach had been dead for several years and I would never get to thank him. Even then, at my age of sixty-seven, he was still teaching me about humility.”

Into Wooden’s final years, Abdul-Jabbar continued to learn about the man he would call a second father and the greatest influence in his life.

In 2008, Abdul-Jabbar interviewed Wooden for a documentary he was producing on the Harlem Rens, what he called the best basketball team no one had heard of. During that interview, Wooden told him of his first coaching job at what is now Indiana State University.

The team had been invited to the National Assn. of Intercollegiate Athletics national tournament, but the NAIA insisted that Clarence Walker, the team’s one African American player, would not be welcome.

Wooden rejected the invitation.

The next year, the NAIA changed its policy and allowed Walker to play. He became the first African American to play in a postseason college basketball tournament. Wooden also explained that when restaurants refused to serve Walker, the team went elsewhere.

“I couldn’t have been more surprised,” Abdul-Jabbar writes. “Coach had been an early pioneer of civil rights, risking his own career, and he’d never told me about it. Any other coach would have used that as a way to gain my loyalty and respect. … What made Coach’s stance all the more admirable, I found out later, was that Clarence Walker wasn’t even a starter.”

And he continues. “I looked at the shrunken ninety-eight-year-old man sitting there … and felt a tenderness for him that I had taken for granted. … I was still learning how deep his influence ran.”

James was sports editor at The Times.

“Coach Wooden and Me: Our 50-Year relationship On and Off the Court”

Kareem Abdul-Jabbar

Grand Central Publishing: 304 pp., $29

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.