Derek Walcott’s poetry had grandeur, an exuberance of language

I discovered Derek Walcott in graduate school after a professor of Caribbean literature recommended “The Prodigal.” I read it slowly, over the course of several weeks, taking in a section or a stanza at a time. His poetry demanded a certain kind of work from me, and I resented that.

But one afternoon, in order to humorously illustrate how many metaphors he could pack into one line, I read a Walcott poem aloud to a group of friends. Halfway through, I stopped to admit that OK, it sounded good. And later, I had to admit that yes, it was good. That Walcott, a more-than amateur painter and well-regarded theater director, had an exquisite ear for sound and eye for image.

The more I worked on listening and looking at Walcott’s poetry, the more love I found for a poet I once resented. His lack of humility, something I’d originally misinterpreted as arrogance, became a form of resistance. I found his language choices unexpected and the images he presented familiar, but made new through his language.

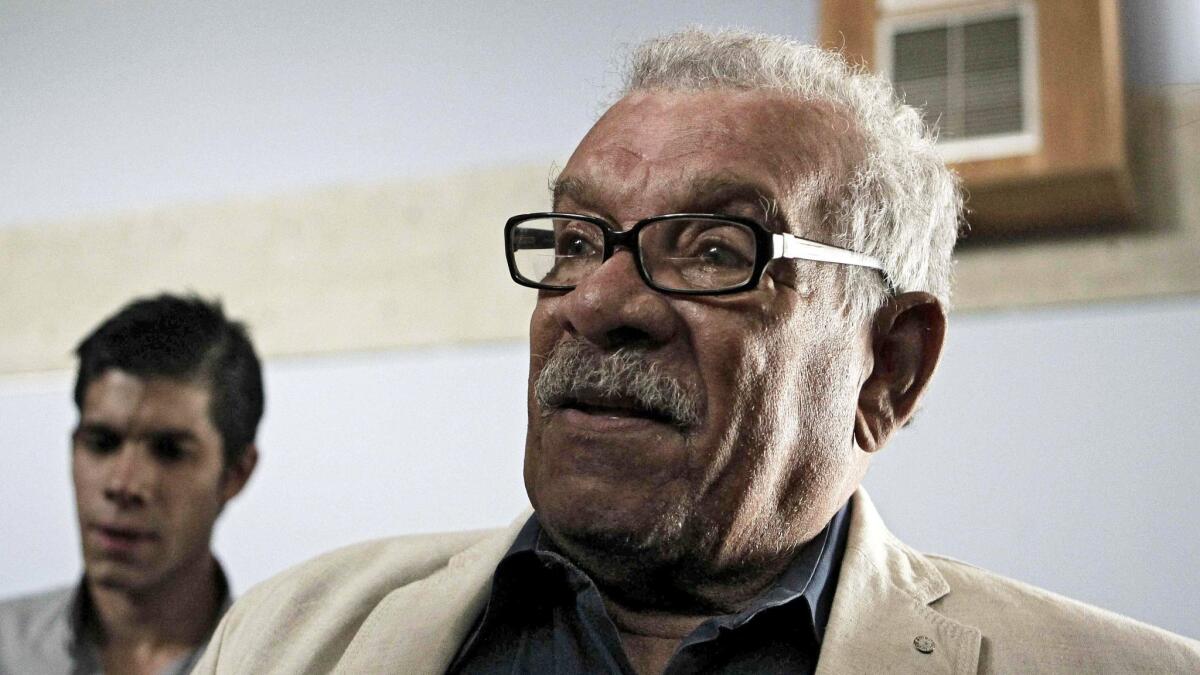

With his passing, we lose a poet of grandeur. He was not without his controversies, and no one would call him modest (least of all himself). But Walcott brought an intensity of conviction, writing through a post-colonial lens, even as he incorporated 19th and early 20th century classically European style with the aesthetics of the Caribbean.

Walcott, who in 1992 won the Nobel Prize for literature, died at 87 on Friday at his home in St. Lucia, the island of his birth, having written 24 collections of poetry, more than 20 plays and several books of essays. For many years Walcott lived abroad teaching and directing theater — often in Boston and New York — but his Windward Islands home always informed his work and worldview.

The ocean is a persistent metaphor in Walcott’s work. The ocean teems with life, sound and unceasing crashing of waves. The ocean is vast and lends its amplitude to Walcott’s voice. There is something to be said for the grandiosity in his poetry.

In a 1985 Paris Review interview, Walcott said, “I come from a place that likes grandeur; it likes large gestures; it is not inhibited by flourish; it is a rhetorical society; it is a society of physical performance; it is a society of style … I grew up in a place in which if you learned poetry, you shouted it out. Boys would scream it out and perform it and do it and flourish it.”

Perhaps that is why, when thinking about Derek Walcott, I keep returning to lines from “Forest of Europe” and “The Prodigal.”

The opening lines of “Forest of Europe” conjure both the tangible and marvelous, without ever succumbing to surrealism or the fairy tale of Magical Realism.

The last leaves fell like notes from a piano

and left their ovals echoing in the ear;

with gawky music stands, the winter forest

looks like an empty orchestra, its lines

ruled on these scattered manuscripts of snow.

The metaphor turns from the very real leaves to notes and then to a shape that registers as sound (“echoing in the ear”), underscored by a smooth pentameter. Walcott escalates the image, moving from an individual note to “gawky music stands,” eventually to a full “empty orchestra” that quickly dissolves into “manuscripts of snow.” The clever use of “lines ruled” evokes the notation of sheet music, college notebooks and the rigidity of form. And the image works — the metaphor of a winter forest as an empty orchestra is haunting and memorable as it is deftly executed.

There is so much more to unpack within the one stanza! I could write a paragraph on the use of “gawky” alone — which is to say, Walcott’s work invites an exuberance in language. Reading Walcott’s poetry can be like confronting a work of art piecemeal; to look at each component closely is to see the image whole — the opposite of impressionism, perhaps.

In “The Prodigal,” a book-length poem, Walcott writes:

I carry a small white city in my head,

one with its avenues of withered flowers,

with no sound of traffic but the surf,

no lights at dusk on the short street

where my brother and our mother live now

at the one address, so many are their neighbors!

Make room for the accommodation of the dead,

their mounds that multiply by the furrowing sea,

not in the torch-lit catacombs of your head

but by the almond-bright, spume-blown cemetery.

In this city of death, there are flowers (withered as they may be), and the neighbors are plenty. There is joy here, “almond-bright.” Walcott’s vision of death is by the sea, which makes sense. The ocean appears throughout his poetry over the decades; the Caribbean never far from his thoughts.

Walcott’s love of the Caribbean defined his poetry and his persona, in sharp contrast to his peer and rival, V.S. Naipaul (another Caribbean Nobel literature laureate who was known for his disdain of the Caribbean). His feud with Naipaul escalated to poetry-slam battle levels, culminating in Walcott reading a poem asserting that “I have been bitten, I must avoid infection/ Or else I’ll be as dead as Naipaul’s fiction.” Walcott was not one to avoid a big gesture.

Grandeur has a bad name these days, perhaps because we associate it with brash politicking. But the kind of grandeur Walcott embodied was different; his was a bold declaration of self and place. What he saw around him, in St. Lucia and throughout the Caribbean, transcended beauty and became muse. Derek Walcott died on the island of his birth, but during his life he gifted the world with the joy and grandeur that he saw. His poetry and his voice never tiptoed. And we all flourished for it.

Ramirez is the author of “Dead Boys” and one of the L.A. Times’ critics at large.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.