Latasha Harlins shooting exposed L.A. race in issues long before Zimmerman

Two decades before George Zimmerman spotted a young man in a hoodie walking through a Florida subdivision, another case involving the shooting of an African American teenager roiled Southern California and exposed racial divisions.

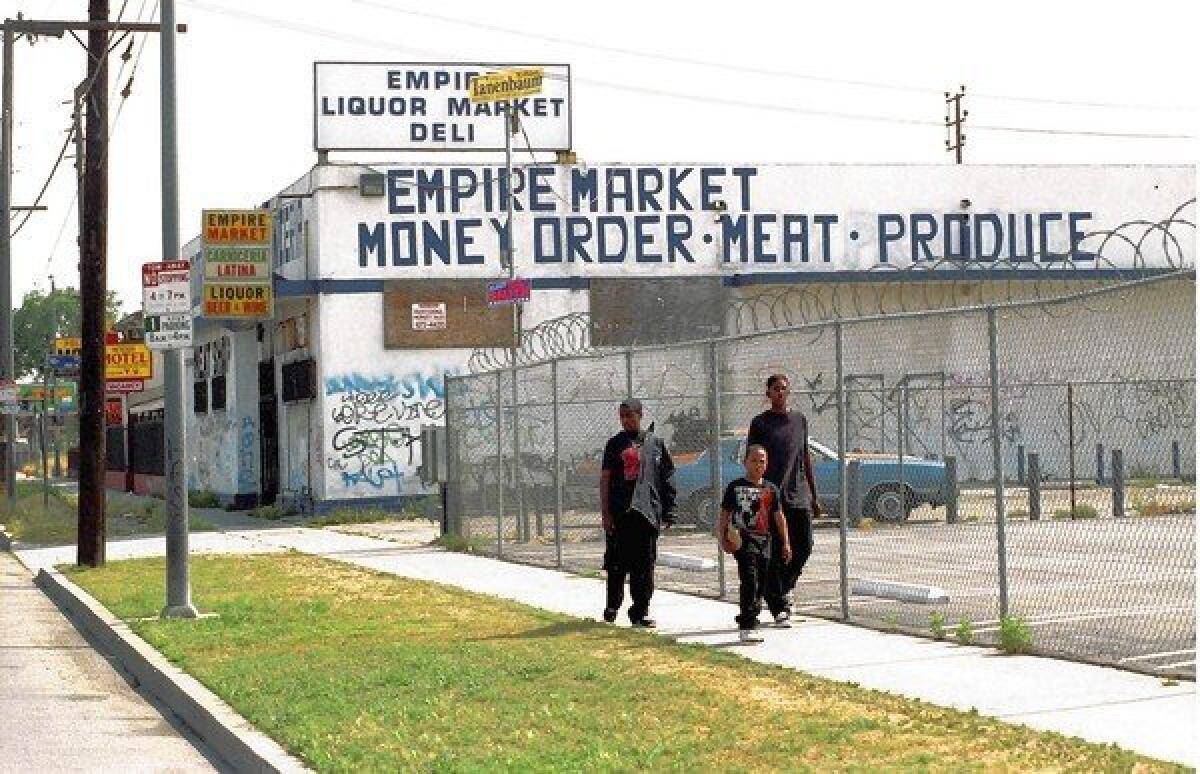

Latasha Harlins was 15 when she entered the Empire Liquor Market on South Figueroa in Compton in 1991. She had two dollar bills in her hand to pay for a bottle of orange juice that cost $1.79, but when store owner Soon Ja Du saw her put that juice into a backpack, Du assumed Harlins was shoplifting.

The fisticuffs and the shooting that followed are now at the center of an excellent and methodically researched new history by UCLA scholar Brenda Stevenson, “The Contested Murder of Latasha Harlins: Justice, Gender, and the Origins of the L.A. Riots.”

FOR THE RECORD:

Latasha Harlins: An Aug. 4 review of the book “The Contested Murder of Latasha Harlins” said that then-15-year-old Harlins attended Westminster High School; she attended Westchester High. Also, the book and review incorrectly said that the Empire Liquor Market is in Compton; it’s in Los Angeles. —

Early in her book, Stevenson offers this concise and compelling description of the young woman who entered Du’s liquor store that fateful Saturday: Harlins was “a girl at heart, with the body of a young woman and an edgy attitude, she was a complex blend of naivete and maturity, strength and vulnerability … anger and heartbreak all wrapped up in a facade of quiet street savvy.”

The Zimmerman trial, of course, featured a similarly complex and ultimately unknowable dead teenager. Watching the coverage of that trial, one longed for storytelling with the kind of perspective and compassion that Stevenson displays in pulling apart the events that ended with Du, a Korean immigrant, shooting Harlins in the back of the head.

There are no villains in “The Contested Murder.” There is just history of the complicated and messy variety that Americans seem to specialize in creating, involving painful issues of race and social class.

Eight months after shooting Harlins, Du went to trial. She claimed self-defense, but a jury found her guilty of manslaughter. Du faced a possible 16-year prison term, but rookie judge Joyce Karlin sentenced her to probation and a suspended prison term. As several media outlets pointed out, Du’s jail time for shooting Harlins was less than the 30 days that another Korean immigrant received for shooting his dog.

African American L.A. was outraged and took to protests, chanting “No justice, no peace.” Five months later, when the LAPD officers who were videotaped beating Rodney King were acquitted, Los Angeles erupted in rioting — with many arsonists chanting “No justice, no peace!”

For Stevenson, these events become the vehicle for a work of deep historical introspection as she untangles the story of the generations of forbears whose striving helped shaped the three female protagonists in the case of the People vs. Du — Harlins, Du and Karlin.

Stevenson’s book takes on topics as diverse as slavery in the American South, the stultifying patriarchy of South Korea and the exodus of Jews from the Russian Empire (Karlin’s great-grandparents emigrated from Kiev to the U.S.).

“Contested Murder” is an academic book. It’s thoroughly footnoted and also begins with the author making theoretical statements typical of such works, with Stevenson asking in her preface what role “race/ethnicity and culture, class, age or gender” or any combinations of these “variables” had on the case of the People vs. Du.

Quickly, however, Stevenson gets to the gritty work of the historian. Her portrait of the Harlinses’ family roots in Alabama and East St. Louis and the family’s eventual journey to Los Angeles is filled with tragic and poignant turns. Time and again, young women in the Harlins family are abandoned by the fathers of their children. We see East St. Louis burn — its black neighborhoods set on fire by whites in 1917.

In L.A., Latasha is 9 when her mother, Crystal, is shot in a bar. In an eerie foreshadowing of the trial, Crystal’s killer — the new girlfriend of Latasha’s father — is given a light sentence. Raised by her grandmother, Latasha is at once lonely, bright and angry. She’s an honor student in junior high but starts missing school when she transfers to the more middle-class Westminster High.

When Harlins enters the Empire grocery, it doesn’t take much to set her off. She will never know it, but she’s crossing paths with a woman who’s also angry and whose family has also made an epic journey.

Like the Harlins family, the Dus story is also told by Stevenson in “Contested Murder,” relying entirely on historical documents and contemporary media coverage. Her book feels as evenhanded as such a work could possibly be.

Du was a member of a rural middle-class family in Korea. Her father was her town’s only doctor, and she grew up relatively privileged. But her ambitious husband brought her to California, where Du and her husband worked in garment factories and other hard jobs to save the capital to become entrepreneurs.

After opening one store in Valencia, Du’s husband opens a second one in Compton, working insanely long hours and commuting 50 miles between stores. Du’s adult son has repeated run-ins with Compton gang members — so his mother decides she’ll fill in for him one Saturday morning.

Unlike the encounter between Zimmerman and Trayvon Martin, the altercation between Harlins and Du was caught on videotape by the store security camera. Du grabbed Harlins’ backpack; Harlins punched Du several times; Du shot Harlins as the teen turned to walk away. The jury found Du guilty of manslaughter. Judge Karlin then decided that justice would not be served by sending Du to prison.

Karlin grew up in a privileged Los Angeles family. But Stevenson describes the rise of that family from its immigrant roots — her father, Myron Karlin, became the head of Warner Bros. — against the backdrop of the history of anti-Semitism in the U.S. in the 20th century.

By placing the story of the women in the largest possible frame, Stevenson arrives at a series of powerful insights about the American experience. At different points in U.S. history and in vastly different ways, blacks, Asians and Jews have all been cast as the “other” and as insidious influences on American life, she writes. And at different times blacks, Jews and Asians have joined forces and found commonalities in their experiences.

In the end, Karlin clearly identified more with shopkeeper Du than with the deceased Harlins. In setting Du free, however, Karlin helped trigger what writer Mike Davis described as a kind of pogrom against the group many came to call the “new Jews” of L.A. — Koreans and Korean Americans, who owned most of the businesses in riot-ravaged South L.A.

To her great credit, Stevenson isn’t afraid to stare all of this painful history in the face and give it the unflinching account it deserves. Koreans remember the L.A. “pogrom” by the name “Sai-I-Gu,” or Four-Twenty-Nine (the date the riots began). “Contested Murder” makes it clear the tragedy inside the Empire Market and the violence that followed in South L.A. and Koreatown should be remembered by all Angelenos as a turning point in their history.

The Contested Murder of Latasha Harlins

Justice, Gender, and the Origins of the L.A. Riots

Brenda Stevenson

Oxford University Press: 432 pp., $29.95

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.