In the podcast ‘The Animals,’ the love between Christopher Isherwood and Don Bachardy is brought to life

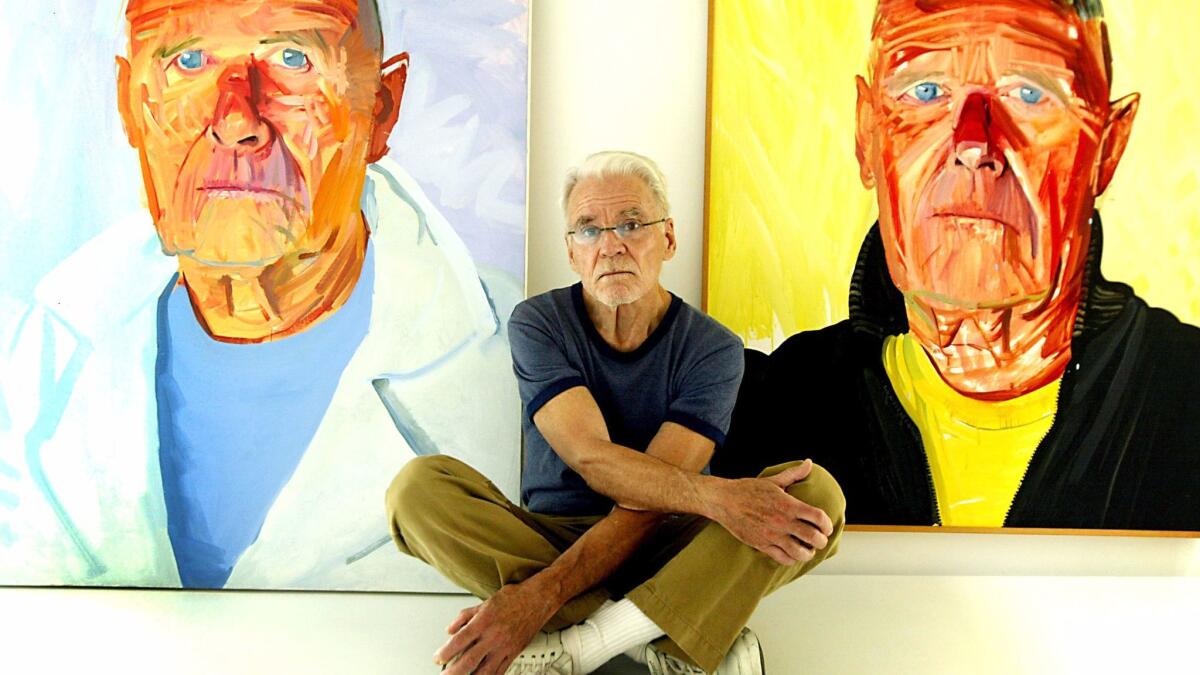

In his novel “A Single Man,” a masterpiece of love and loss, Christopher Isherwood wrote, “As for the animals, those devilish reminders, George had to get them out of his sight immediately; he couldn’t even bear to think of them being anywhere in the neighborhood.” George, an English professor in Los Angeles, mourns the death of his much younger lover, Jim. George and Jim are loosely based on Isherwood and his lifelong companion, Don Bachardy, a celebrated portraitist 30 years his junior. During a particularly volatile time in their relationship, Isherwood killed off Bachardy in the fictive world of “A Single Man,” imagining a life alone, where even their animals were “devilish reminders.”

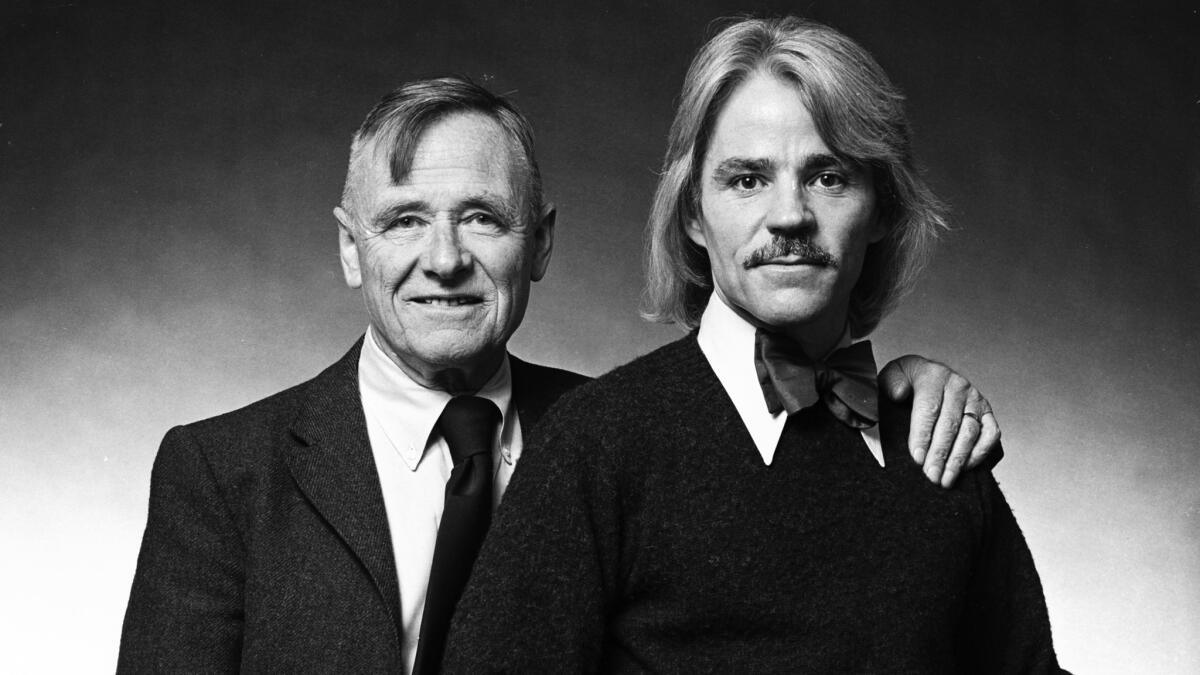

Actors Alan Cumming and Simon Callow play Bachardy and Isherwood, respectively, in a new literary podcast called “The Animals,” produced by Katherine Bucknell, who heads the Isherwood Foundation. Callow and Cumming read from the letters of Isherwood and Bachardy in episodes that follow the trajectory of the love between these two unconventional yet paradigmatic lovers.

Cumming, who won his Tony Award playing the Emcee in a revival of “Cabaret” — a musical based on Isherwood’s most famous work, “Goodbye to Berlin” — is an ideal mincing Bachardy, exuding both boyish naivete and feline intensity. Callow’s stately Isherwood is the perfect counterbalance. You can hear in his voice an aging man trying to keep it together, yet the performance allows us a glimpse of the cracks in Isherwood’s polished façade.

Simon Callow reads Christopher Isherwood, with an introduction by Katherine Bucknell

Alone in a cabin in the woods, listening to these voices flirting, and yearning, and quarreling, I felt as though I was privy to something private, something intimate, but something grand.

Dobbin and Kitty

In their correspondence, Isherwood and Bachardy referred to one another frequently as “the Animals,” each taking on the role of a particular creature: Isherwood was Dobbin, a “stubborn, gray workhorse,” and Bachardy was Kitty, a “skittish, unpredictable, white kitten.” This campy game of pet identities discussed in the third person — this “Animalese,” as they called it — gave them the ability to express and expose themselves in ways they may have otherwise been unable, revealing the complications of commitment, love and sex in a gay May-December romance in the latter half of the 20th century. “The Animals” of the podcast’s title, then, refers to this game the lovers played, but there are also reverberations with Isherwood’s work, for the author constantly showed in his writings a fascination with our animal creatureliness.

In “A Single Man,” for instance, Isherwood described George as “the creature we are watching.” In the secret world of the letters, Isherwood and Bachardy appear, like George, as creatures we are hearing — strange beasts torn between the call of the wild and a different call, one of domestication, of companionship, of commitment.

Alan Cumming reads Don Bachardy, with narration by Katherine Bucknell

Each episode follows the lovers (and their faunal totems) at a particular moment in their lives, through good times and bad. Bucknell, editor of Isherwood’s four-volume set of diaries and the book of letters on which the podcast is based, acts as curator and narrator here, interjecting often to give the letters context and the story shape. For additional accoutrement, the episodes sometimes include bits from Isherwood’s diaries and guest appearances, including one by David Hockney.

Emotions Isherwood could never novelize

Though “A Single Man” is tangentially about his relationship with Bachardy, these letters are the great unwritten book of their relationship, and listening to these selections, buttressed by an emotive score by composer Edmund Jolliffe, one can often hear Isherwood’s lyricism, even, and perhaps especially, in moments of rage and desperation, when a lesser writer might lose his grasp of language.

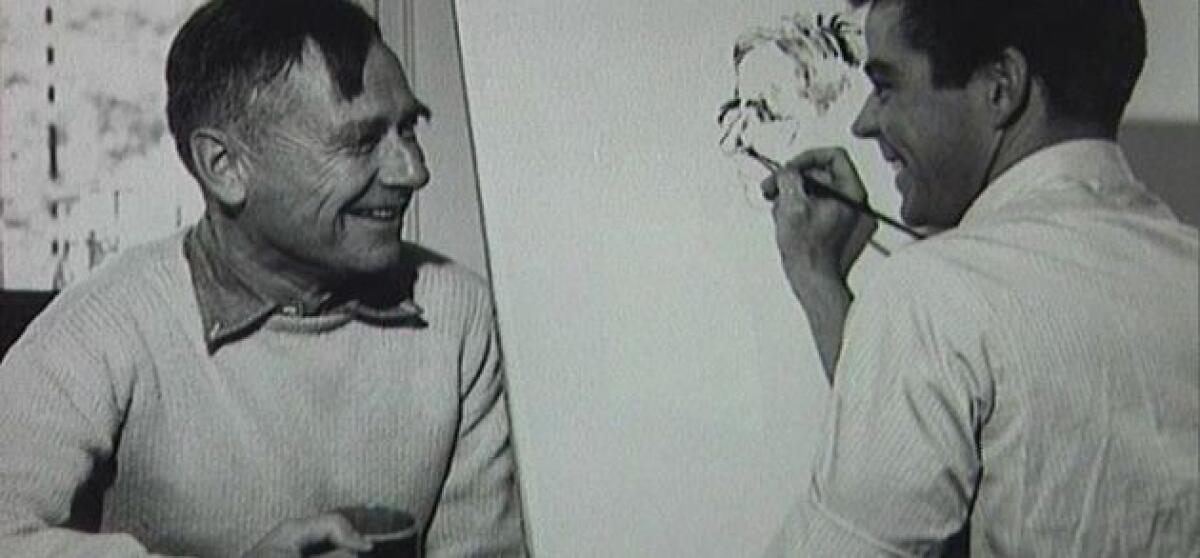

“Oh — I am so saddened and depressed when I get a glimpse, as I do so clearly this morning, of the poker game we play so much of the time, watching each other’s faces and listening to each other’s voices for clues,” Isherwood wrote to Bachardy in 1963, during one of their most trying years. At the time, Bachardy was finally achieving a certain level of success as an artist and growing into his own as a man, taking on other relationships, keeping more elaborate secrets.

Isherwood continued, “And then you say, for example, Dobbin’s in a strange mood, and then things start to get tense. And, because I know this, I start playacting to get them untense again, and that makes everything worse. And you are much the same. Although, somehow or other, you always seem franker than I am. Is that because you can afford to be? Am I scared of you? Yes, in a way. But I really almost wish I could be more scared.”

These letters allow us to approach the complicated emotions that Isherwood could never adequately novelize. While we will never fully understand their love — for it, like any true romance, remains elusive not only to outsiders, but even to those involved — these episodes do allow us to take these animals in our hands, hold them to our bosom. In the push and pull between the call of the wild and the call of domestication, we glimpse the very thing we all seek: unbreakable connection and indefinable love, in their truest, most pure forms.

An enduring love

“The Animals” podcast is (just as “the Animals,” Isherwood and Bachardy, are) a “devilish reminder” not only of the forces — political and cultural, societal and familial, mutual and individual, bestial and hominal — that conspire to snuff out the bright burning light of love, especially that of the homosexual variety (the love that only in very recent human history dares to speak its name), but of the ability for that love to survive and somehow flourish amid such opposition.

In 1963, that darkest of years for the pair, Isherwood inscribed a copy of his novel “Down There on a Visit” to Bachardy, “Let’s put our faith in the Animals. They have survived the humans and will survive.” In listening to their letters, we bear witness to this animal endurance — a survival of the fittest love — one sure to leave us yearning for our own creaturely connections.

Malone is a writer and professor of English. He is the founder and editor-in-chief of the Scofield and a contributing editor for Literary Hub.

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.