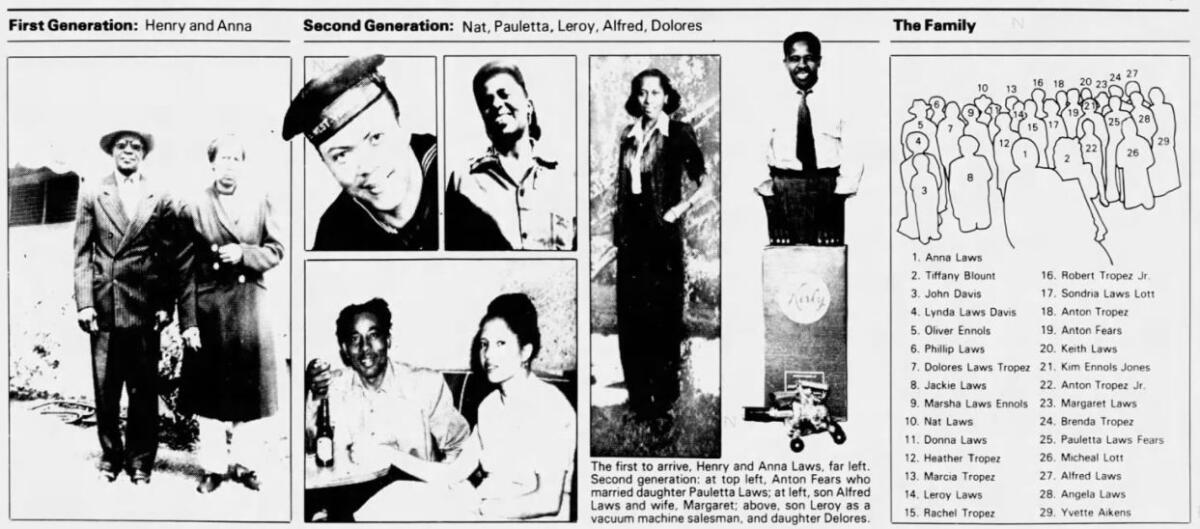

Four generations: A family mirrors roots of black L.A.

This story originally ran in 1982 as part of the “Black L.A.: Looking at Diversity” series. Please note: Our standards on certain terms have changed, but we have preserved the original text in order to provide an accurate account of the work in print.

Anna Laws rests easy these days.

Debilitated by a stroke, she quietly whiles away her time in an easy chair near the living-room window, watching her neighbors pass in front of her home near 92nd Street and Central Avenue.

Anna has lived through most of Los Angeles’ modern history. She and her late husband, Henry, were part of it. Their names and the U.S. Supreme Court decision that rose out of their struggle for the right to live in their home were long ago submitted to record in various history books.

She has lived through 14 Presidents, four wars, the assassination of a President, then his brother, and the slaying of “The Dreamer,” Martin Luther King Jr., at a Memphis motel. There were tears over the mysterious death of her grandson in a Reno jail cell, and again as she watched another locked away in Soledad Prison for murder. And joy when a third grandson was appointed to a presidential commission by Jimmy Carter.

Anna has seen the celery fields where her children once chased jackrabbits — in a semirural subdivision called Watts — transformed into homes, apartment complexes and businesses. In 1965, she saw those businesses go up in flames. And she saw a city whose racism shut her family out of jobs, housing and recreation — and that once even jailed her for living in her own home — elect a black mayor.

The legacy of her family is that of most of the 505,000 blacks living in Los Angeles — one forged in sweat, suffering, compassion, laughter, tears and sometimes blood.

In 1910, Anna and Henry Laws packed their meager belongings and their three-month-old son, Nat, onto a Southern Pacific train and left Rosenberg, Tex. for Los Angeles.

Henry’s brother, who was already in Los Angeles, had told them of the limitless possibilities that existed. Henry, however, soon found that there were lots of limits on the fledgling black community of 9,242, or about 2.3% of the city’s population.

Jobs were hard to come by and much of the racism he thought he had left in Texas was here in Los Angeles. Still, he managed, mostly by working odd jobs and hauling junk. In the next two years, Anna gave birth in the back bedroom of Henry’s brother’s home to daughter Pauletta and then son Leroy.

In the summer of 1982, The Times published a series on Southern California’s Black community called “Black L.A.: Looking at Diversity.”

World War I came, but Henry did not serve in the military, mostly because the armed forces discouraged blacks from enlisting, even refusing to take them into some branches, such as the Army’s aviation section.

On July 12, 1918, as the war was ending, Henry and Anna’s fourth child, Alfred, was born. The next year, the family moved to Gardena, then later to Imperial Valley, where Henry and Anna eked out an existence in the cotton fields before returning to Los Angeles in 1921.

In the interim, the number of blacks in Los Angeles had nearly doubled to 15,579, most of them clustered around Central Avenue from 5th Street to Jefferson Boulevard. An active business center had developed around 22nd Street and Central, anchored at Washington by the Clark Hotel, then the only hotel in the city that accepted blacks.

The Laws family moved again, this time to Ruby Street, between 117th and 118th streets, where Anna had purchased two adjacent lots. While the house was being built on one lot, the family, now seven with the birth of Dolores in 1921, lived in a tent on the other.

Nat: “We were the second Negro family there. At that time, Imperial Highway was the dividing line for Negroes. We went to Willowbrook School. I remember I had to fight like hell every day going to school. It was like a war, fighting them white kids. For fun, we played with these coasters that we made out of old skates and 2-by-4s. But in our neighborhood, we didn’t have any sidewalks, so we’d have to go in the white folks’ neighborhood to ride the coaster on the sidewalk. We’d be coasting along and then — bang! — three or four white boys would gang up on us and run us back to our neighborhood.”

Leroy: “We may not have had a lot of things we wanted, but we never went hungry. Daddy was the kind of man who liked to work for himself. He was one of the few people that had a truck, so he would always do a lot of hauling. He had a little sign on the side of the truck that said ‘Express Hauling.’ He was a hustler. Not the way they use the word now. He was always swapping and trading. He would go away and always come back with something, whether it was chickens or whatever. Later on, he started doing a lot of landscaping for contractors and people’s homes. It was hard for Negroes to get jobs then, so he just did a lot of different things to make ends meet.”

Dolores: “Mother was a domestic for as long as I can remember. She used to work in different white folks’ houses, like on Crenshaw near Victoria and up in Hollywood. I remember she was always working hard and always buying special things for the house. Like we got a crystal radio and a washing machine long before a lot of people, and momma got drum lessons for Alfred and dance lessons for me by trading a day’s work with the instructors for our lessons.”

Alfred: “In those days, all out here was country. Except for Imperial Highway, just about everything else was dirt. Back then a lot of blacks didn’t have electricity. We had kerosene lamps. Listening to the radio was a big thing. You’d have it hooked up to a car battery. That was just before (Charles) Lindbergh flew the Atlantic Ocean. I remember that the lady next-door used to sing that song, ‘My Blue Heaven.’ I think Nat and Pauletta quit school about then.”

Nat: “The Depression hit in 1929, and man it was rough. I worked at Compton and Firestone in the barbershop shining shoes from 7 a.m. to 5 p.m. I was about 17 or 18 at the time. I only made $9 a week. I didn’t quit because there were no other jobs.”

By 1930, Los Angeles had grown to a whopping 1,231,730 in 10 years. The black population had more than doubled to 38,894, 70% of them huddled into houses in a district anchored by the Watts subdivision.

Leroy: “Watts was like a little town, and whites ran damn near everything. All the school teachers were white. Things were rough then. No jobs, no nothing. Like it’s getting now. They used to have bread lines. The government would come and deposit food at the fire departments. They would have so many boxes of food sitting all over the trucks that they couldn’t fight a fire if they wanted to. Most of the men worked on the WPA (Works Progress Administration) and people would load up on the back of trucks to go up in Bakersfield and pick cotton or pick oranges or swamp watermelons.”

::

As scarce as jobs were during the Depression, hiring biases made them even more scarce for blacks. In 1933, there were 81 white-operated businesses on Central Avenue between 28th and 43rd streets. Three-fourths did not hire blacks although blacks made up 85% of their trade.

I was the same at the manufacturing plants. In a USC survey in 1933, managers at 51 plants were asked their attitude about hiring blacks; 37 gave reasons for not hiring blacks.

The Los Angeles Department of Water & Power refused to hire blacks for a large construction project on the grounds that it did not have separate camp facilities. Objections from white parents and the refusal of white instructors to share eating and toilet facilities with blacks kept black teachers out of the city’s high schools and junior high schools until 1936.

When blacks did find work, it was almost always of the most menial kind. In a six-month period in 1932, 80% of the black men filing for work at Urban League offices in Los Angeles listed their last occupations as non-skilled jobs — janitors, laborers, chauffeurs, butlers, cooks and housemen.

Of the black women seeking work, 71% of them had been domestics or maids — “kitchen mechanics,” as they were dubbed by blacks. The remainder were laborers, cooks, waitresses and seamstresses.

Access to even those jobs became more difficult as the Depression dragged on and whites, once scornful of such work, began filling them. In the midst of such difficult times, the second generation of Laws were now moving into adulthood.

Nat left the city in 1929 and went to work on Santa Catalina Island, then in its heyday. (He would remain there for 11 years, first working as a janitor, later as a helper at the island’s airport, and finally as an airplane mechanic managing a crew of four.)

Leroy worked on Catalina periodically; Pauletta, too, but for the most part she worked as a domestic for white families in Hollywood who were part of the city’s growing movie community. In 1936, Alfred dropped out of school.

Alfred: “It didn’t matter if you had a high school education or not. There were no jobs for negroes. In those days, they would openly tell you, ‘We don’t hire colored.’

“I never will forget how when I was coming out of school, the teachers — they were all white then — would take the white kids and explain to them what to do about getting a job. But they didn’t waste their time talking to us because they knew there was nothing out there for us.”

Dolores: “When I graduated in 1939, they gave most of the Negro girls cooking courses and home economics courses. I said, ‘Heck, my mother is going to teach me how to cook.’ They told me I couldn’t change, but I started taking commercial courses, typing and shorthand and stuff. When we finished, the whites went to work in good jobs at Bank of America and in office buildings and things. Most of the Negro girls became domestics.”

That year, the average expenditure for an elementary school student in Los Angeles was $105.49 per pupil, but in the elementary schools in the Jefferson district, where the largest number of blacks were congregated, it was only $67.52.

::

Just as blacks were excluded from jobs, so were they barred from much of the city.

Nat: “Out in Hollywood and West Los Angeles, Negroes couldn’t live in those neighborhoods. And Huntington Park? Man, a Negro couldn’t walk the streets in Huntington Park. I remember on every corner, they had a sign on a six-foot pole that said ‘No Negroes or Orientals Desired.’ It was almost as bad in Culver City.

“There was a time you couldn’t go to the beaches. Then they finally roped off a place, about 200 feet, for the Negroes to go. Just because you were in California, it didn’t make no difference.”

Dolores: “Downtown, they wouldn’t let the Negro women try on the hats. At one time, they’d give women a piece of tissue paper to put on their heads before they put the hats on. The Largo Theater on Central was even segregated then. They had a velvet rope and blacks went on one side and white went on the other. Even after it changed, blacks still went to that side for a while, out of habit, I guess.”

Nat: “It was more or less a standoff. The Negroes had their own places where they went and the white people had their places. The Negroes, the Mexicans and the Orientals, they got along fine. But if you went where the white man was, you got in trouble. So, you just stayed the hell away from him, see.”

Thus, Central Avenue became the heart of black life in Los Angeles. Whites dubbed it “Harlem.”

At 43rd and Central was the Dunbar Hotel, where famous blacks -- Lena Horne, Joe Louis, Duke Ellington, Cab Calloway, Louis Armstrong and the like — would stay when they visited the city because white hotels would not house them.

There was the Avedon Ballroom, and later on the Lincoln Theater, where a young Sammy Davis Jr. would tap dance and sing on amateur nights. Farther down at 118th and Central, the Brown Sisters, a vocal trio, opened a nightclub called Little Harlem, where blues singer T-Bone Walker would become famous. And every now and then, the Shrine Auditorium would be open to blacks.

Alfred: “But the main stomping ground was the Five-Four Ballroom. If you weren’t jitterbugging, you were boogie-woogieing. Thursday nights were ‘kitchen mechanic night’ because all the young black girls who worked as live-in maids in Hollywood and Westwood and places like that would be off that night. The clubs down Central Avenue would be hopping.”

Leroy: “Everything happened on Central Avenue. I remember one day I was walking down Central and I saw all these Negroes lined up outside the Dunbar Hotel. I said, ‘Man, what’s the line for?’ They said, ‘We’re going to be in the movies. Tarzan is making another picture.’ You’d get in line, they’d take your name and if you looked the part of an African, you’d be in the movie. They paid about $2 an hour. Domestics were only making 50 cents an hour then.”

MGM made lots of Tarzan movies, almost one every year from 1932 to 1947. It was one of the few opportunities for blacks to work in movies. Few moviegoers outside of Los Angeles ever knew that the Jujus, Kibonis and Watusis chasing Johnny Weissmuller through the jungle were really black people from Watts, or that the Senegalese soldier in the 1938 movie entitled “The Enforcers” was actually Alfred Laws of Ruby Street.

::

On Dec. 7, 1941, the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor. On the sunk U.S. ship West Virginia was a black sailor named Anton Fears, Pauletta Laws’ fiancé.

Pauletta: “I was working as the swing girl at three hotels — the Santa Rosa, the Russ and the Panama — when it broke out. I was on my way from the Santa Rosa Hotel at 4th and San Pedro to the Panama on 5th Street at the time. I passed by a window and heard that Pearl Harbor had been bombed. People panicked as they would after a big earthquake. Pandemonium broke out. People were excited and running. I knew Anton was in Pearl Harbor. Naturally I worried about him. I couldn’t get any information about where he was or what had happened to him. Then I heard that his ship had gone down, and I was really worried. It was a month later before I found out he was safe.”

Four days later, America was at war. Soon, blacks began streaming out of the South and Southwest to the nation’s urban centers in search of jobs created by the wartime economy.

At first, many of them avoided Los Angeles, warned off by black newspaper accounts and letters from relatives here describing the discrimination that barred blacks from jobs in aircraft plants and shipyards.

“Regardless of their training as aircraft workers we will not employ Negroes … It is against company policy,” wrote the president of El Segundo-based North American in the spring of 1941, echoing the sentiments of many of his colleagues.

Unions at those plants, such as the AFL’s International Assn. of Machinists and International Brotherhood of Boilermakers placed blacks in a double bind by barring them from membership until 1942.

Nat, who had returned from Catalina with his wife and two sons -- the first black children born on the island -- tried to get a job at one plant.

Nat: “I went to the aircraft people over here and showed them what I could do. A lot of them knew me from Catalina. But they wouldn’t hire me because I wasn’t in the union. But the union didn’t admit Negroes. The guy told me, ‘Nat, I know you can do the work, but we’ve got 100 mechanics out there and they belong to the union. If we give you a job, those 100 mechanics will walk off. But if you want a job you can clean up.’ I said, ‘No, thanks.’”

But as wartime production increased, creating 550,000 new jobs in Los Angeles at the same time the city was losing 150,000 men to the draft, the companies and unions relaxed their policies, and by the summer of 1942, blacks, mostly from the Southwest, began arriving at a rate of about 300 a day.

By the summer of 1943, when Nat’s third son was born, the migration had reached its peak. About 12,000 entered the city in the month of June alone.

Nat: “By me being out here and never having been down South, I never imagined there were so many Negroes in this dog-gone country. I said to my dad one day, ‘Jesus Christ, dad, where are all these Negroes coming from?’ He said, ‘From down South. You don’t know it, but there are whole cities of nothing but Negroes down there.’ I said, ‘Well, the damn cities must be empty now because they’re all out here.’ They were coming like blackbirds. It made me nervous. I wasn’t used to so many Negroes.”

By mid-1942, the forcible evacuation of people of Japanese ancestry, many of them American citizens, was under way in Los Angeles. Thousands were sent to camps in barren Owens Valley.

Among those taken was Shinishi Nishimoto, who owned a small grocery at Imperial Highway and Central Avenue.

Nat: “The Japanese were leaving and he had to get rid of his store. I didn’t have much money, just $600. He said he would leave it up to me to pay the bank and when he came back, he’d get the store back. He signed everything over to me. I paid off the bank and they still hadn’t come back. He said, ‘Send me $3,000 and you keep the place.’ So, I sent him a check for $3,000. I didn’t have to send him the money if I didn’t want to because the store was already in my name. It was just a gentlemen’s agreement.”

Pauletta and Dolores went to work at Lockheed as riveters, helping to supply planes for a war effort that raged on two fronts. As in World War I, the military continued its segregationist policies.

Alfred: “When I was drafted in 1944, they took the Negroes into this room away from the whites and Mexicans, and showed us the uniforms that we would be wearing as mess attendants. They gave us this big story about how we would be safe and how we’d be working around the food and always have something to eat. We wanted to be in the seaman’s branch just like the whites. But they made it clear to us that we wouldn’t.

“The army was segregated too. But they had all-black units. Even had a few black officers. But what few blacks were in the Navy, you did nothing but serve them damn peckerwoods. You kept their shoes shined, you made up their beds, you cooked their food and you waited on their tables. Later on, when the Japs started raising hell, about ‘44, ‘45, they let blacks come in like the whites.”

During the war, a new militancy arose among blacks. The constant talk of the war being fought for democracy grated on most as so much hypocrisy.

Nat: “Negroes had a different attitude. If one went into a place and a white man refused him service, he’d wreck the damn place. Those Negroes came here from down South wanted to get even anyway.”

No one had expected it and no one intended it, but the war became a watershed of the struggle for equality. The number of blacks in manufacturing almost tripled in three years, and the number in government jobs increased fourfold. Civil rights organizations flourished. The Urban League tripled in size. The NAACP did even better, growing from 50,000 members to 500,000 by 1945.

Like many Los Angeles families, the Laws family dutifully supported the war effort. They bought war bonds regularly as members of the Bond-a-Week club. They hauled refuse to salvage areas. Henry worked as a janitor at a defense plant. Pauletta had married Anton Fears and had seen him receive a Purple Heart for his action at Pearl Harbor and return to war.

With the money Henry and Anna saved, they built a home on one of two lots on 92nd Street that Henry had bought 13 years earlier. In October, 1944, they moved into the neighborhood shortly afterward.

All three families were treading on dangerous ground. To keep blacks from living in their communities, whites had devised restrictive covenants, clauses in housing deeds that prohibited occupancy by anyone other than Caucasians. Consequently, until Henry and Anna moved into the area, “there wasn’t a black face around.

In November, two real estate developers filed suit, claiming that the families had violated the restrictive covenants. A superior Court Judge upheld the claim and ordered the families to move by Dec. 1 or face five days in jail for contempt of court. The two other families moved. The Laws did not.

Nervous NAACP officials, fearing that they could not win the legal battle, offered Henry $750 to move. He refused.

“Why should I move,” he said in court. “I bought this property 13 years ago and I built this house. I bought the furniture to fit the rooms. The only way they will ever get me out of this house is to shoot me with a Gatling gun and throw my dead body on the other lot. I am a free-born American citizen. My sons are fighting the Japs in the South pacific. I buy war bonds. I am working for a defense plant, and so is the rest of my family. No judge will ever put me out and the United States government will never put me out.”

A few days later, sheriff’s deputies were at his door. When they arrived, the Laws home was a beehive of activity as neighbors, friends and various organizations rushed to their aid. Inside, a food committee prepared hot dogs and hamburgers for the pickets outside protesting the decision.

There was confusion — and some amusement — when one of the white deputies suddenly appeared in the kitchen. He calmly waited his turn for a tray filled with hot food and then carried it outside to serve the pickets.

Finally, Henry, 57, and Anna, 56 — their son who served in the Pacific, their son-in-law awarded a Purple Heart, and stacks of war bonds in their house — were carted off to jail for living in their own home. Pauletta, still living with her parents, was arrested that night after she came home from work.

Alfred was based in Seattle when he heard of his parents’ arrest. Furious, he jumped ship when it pulled into Los Angeles Harbor.

Alfred: “I said, ‘Why should I put my life on the line when they are doing this to my people over here.’ They say you’re fighting for your country. What kind of country am I fighting for that puts my parents in jail for living in their own house? To hell with Uncle Sam. I might as well be fighting right here.”

After five days, the Laws were released, just in time for Pauletta to greet her husband who was home on leave from the military.

By his stubbornness, Henry Laws had forced the NAACP’s hand. To defray the legal costs, civil rights groups, churches and four different Communist Party cells held rallies to raise money. Charlotta Bass, editor of the California Eagle, championed their cause in her black newsweekly and drummed up support among influential friends like Lena Horne and Paul Robeson, who both contributed money.

On May 3, 1948, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that racially restrictive covenants were unenforceable.

The Laws family celebrated.

Delores: “We were very happy and jubilant about it. We received calls from people congratulating us, you know, all the people from around the neighborhood who had helped us by raising money and canvassing and picketing. People would call and stop by and say, ‘I’m glad your mother and father didn’t give up’ … That went on for a long time. Even now, some of the old people who remember it will say something about it when they hear the name Laws.

“I was very proud. We felt it was our right to live in it. We felt we would win because we were right. It was just a nice feeling that stayed with you for a good while.”

In 1948, there were 22 major hospitals in Los Angeles. Only one would accept black patients. Housing discrimination kept blacks boxed in around Watts, and blacks continued to face open job discrimination.

Alfred: “I applied for a job with the Department of Water & Power as messenger clerk. That was in 1950. I would have been working in the downtown office and delivering messages and packages and mail to the branches in outlying areas, El Segundo and places like that. I took the Civil Service test and passed it. I don’t think they expected me to pass.

“They told me, ‘Now, we’ll give you the money, but we’ll have you cleaning up the restrooms, sweeping the hallways and the courtyard. Your title will be messenger clerk, but you’ll be doing janitorial work. We just can’t have a young Negro man working in the offices with these young white girls.’

“They told me that. I was so mad and despondent, I didn’t know what to do. I said, ‘If that’s the way you feel, I don’t want the job.’ But man, I needed that job. I really needed it.”

::

By the mid-1950s, California and its principal city had become the envy of the rest of the nation. Asked to choose their favorite vacation spot, Americans regularly chose California first, Hawaii second.

The Cold War between America and the Soviet Union rained down riches on the state. Defense contracts created hundreds of thousands of jobs in Southern California and by the end of the decade, the state’s share of prime defense work exceeded that of New York and Texas combined.

And the people kept coming. Of the 15 largest cities in the 1950s, 14 lost population. Los Angeles alone grew larger.

By now, most of Henry and Anna Laws’ children had settled comfortably into adulthood:

— Nat had divorced and remarried. He would continue to run his store until the Century Freeway and rising crime would prompt him to sell and move to three acres in Perris in 1975.

— Alfred also was in his second marriage. He would work for the Department of Water & Power as a cement spreader for 28 years before retiring and amassing the trappings of middle-income status.

— Pauletta and her husband bought land on 90th Street and built a comfortable two-story home there. Her husband would work for the Department of Water & Power for 11 years before leaving for a job as a dispatch clerk for a major manufacturer. Pauletta, after working at a packing company and selling display advertising for the California Eagle, would work for 13 years with Nat in his store.

— Dolores raised her three children and worked sporadically. Her husband, Robert Tropez, the first black security officer at City Hall, would become head of the department before retiring in Compton.

— Leroy, divorced, lived with his mother and worked as a cable splicer for the Department of Water & Power, then ran a janitorial service. Alcoholism would force his retirement.

Meanwhile, their children, the third generation Laws in Los Angeles, were beginning to take their own place in society. Henry, the oldest of Nat’s three sons, had fled Watts after graduation for the Marine Corps.

Henry: “I wanted to get away. On my way to high school, I would pass through the neighborhoods in that area and I could never understand why I lived the way I did, which was extremely poor, and why other people were able to live in the better neighborhoods. Their homes had nice lawns, there were sidewalks and lights on the streets. Where I lived, there were no sidewalks, the streets were unkempt and the people were very poor people. I felt trapped. I just kept saying to myself, ‘I shouldn’t have to live like this.’ I couldn’t believe the whole world was like where I was living. I resented being at home. I just wanted to get the hell away. I would have dropped out of high school, but my Aunt Pauletta convinced me to stay.”

His brother, Joseph, left school in his senior year and followed Henry into the Marine Corps. Phillip, the youngest, was finishing high school.

So was Alfred’s daughter by his first marriage. Three other children ranged from 5 to 5 months. Two more were yet to be born.

Leroy’s daughters, Marsha and Sondria, were nearing graduation at Fremont High School. Delores’ children, two boys and a girl, were still under 10.

By 1961, much of the city’s and the nation’s attention was focused on the space race as Alan Shepard Jr. became the first U.S. astronaut. Henry, Nat’s oldest son, with some college behind him, had started work at the post office. His brother, Joseph, drifted in and out of the military. Phillip, the third brother, graduated from school and went to work at a department store, then worked as a driver-salesman for a potato chip manufacturer and later as an insurance salesman.

When her parents could not afford to send her to college after graduation, Sondria, Leroy’s daughter, went to work for the Department of Social Services, making $292 a month, a “big time job,” and married a high school classmate.

Her sister, Marsha, also married her high school sweetheart. They struggled financially until he passed the Civil Service exam and became a cable splicer for the Department of Water & Power. The next year, she found a job at Douglas Aircraft.

Marsha: “It was part of some kind of affirmative action program. They hired me and another black woman named Glodean Jordan. You were supposed to take a typing test, but they were trying to get us in there so fast that they waived it. Out of 400 people in that area where we worked, there were five blacks.

“Our job was to type out these orders. First we had to make it through our probation. They told me and Glodean that the quota was 100 orders a day. After a few days, I came home in tears. I told my husband I wasn’t going to keep the job. I made it up to 95, but I just couldn’t do 100. We needed that job. All the while, the white women there were laughing at me and Glodean because we were working our tails off while they were taking things so easy. We found out later that the reason they were laughing was because the supervisor had lied to us about the quota. It was only 50.”

Less than a month later, President John F. Kennedy was assassinated, signaling a decade of uncertainty. That same year, a black former policeman, Tom Bradley, won election to the City Council.

The summer of 1965 began on a high note. A nation beamed with pride as Gemini 4 landed in the Atlantic in June after the longest manned space flight in history. Civil rights leaders felt they had found a friend in President Lyndon B. Johnson, who had declared war on poverty. Various programs — Headstart, Manpower and the like — began to pop up in Watts.

But to many, the seeds of hope had been planted too late.

On August 12, Alfred’s wife gave birth to their last child, and the same day Watts erupted in a fury of violence and destruction that would shake the nation.

::

Black rioters poured into the streets, burning and looting stores and businesses throughout the South-Central area.

In the middle of their path was Nat Laws’ Highway One Market.

Nat: “They tried to burn down my store. I said I’ll be damned if I’m going to work for 20 years for nothing. I grabbed my shotgun and said, ‘OK, you fools want to die, you can die.’ One of them said, ‘We’re after whitey.’ I said ‘If you’re after whitey, go get whitey and leave me alone. What’s the matter, you crazy or color blind?’ It was like a war down there. I stood them suckers off for 21/2 days.

“Henry and Phillip (his two sons) came down to help me. I was the only store left for miles around. I didn’t get no sleep. After 21/2 days, I couldn’t take it. Then here come four police cars down the street blowing their sirens. I hollered and said, ‘I’m glad to see you. Give me some help.’ They just looked out of the car and kept going. They wouldn’t get out. I didn’t really get scared until then.”

Henry: “Instead of being a part of it, at that time I saw it as a threat to my security because I was working part time at my father’s store and I needed that money for my kids. I was hostile against the riot. I couldn’t understand why, if I was mad at the system, I would burn my house down. I could see what they were doing, but I couldn’t understand burning down your own neighborhood.

Sondria: “People were looting everything. I was like it was a big market and people had just decided they were going into the stores and take whatever they wanted. I remember we were going down the street and we saw this boy with a big rack of nothing but bread. We turned the corner and they were looting the Safeway on Imperial Highway.

“Joe (her husband) was driving. We picked up my mother, my sister and my niece and returned to the market. Joe went in. The police came by and looked and just kept going. He loaded up on all kinds of stuff.

“Then the National Guard came in. They sort of boxed in the area and they weren’t letting nothing black out. You couldn’t go east of Alameda, west of Crenshaw, south of Imperial or north of Washington. Some people said they were afraid, but I wasn’t. I was in my neighborhood with people I had known all my life.”

When it was over, 34 people lay dead, 1,032 had been injured and $40 million worth of property had been destroyed.

::

For two years, death and the prospect of death would haunt the Laws family. In 1967, as urban riots and Vietnam War protests swept the nation’s cities, Henry Laws Sr., the family patriarch, died. A few months later, the youngest daughter of his grandson, Henry, died from the cerebral palsy that had afflicted her since birth.

That same year, Dolores’ oldest son was drafted into the Army. A year later he was in Vietnam, where he would serve nine months before returning home.

In April, Martin Luther King Jr. was slain, and two months later, Robert F. Kennedy was gunned down in Los Angeles’ Ambassador Hotel.

Pauletta: “Pandemonium broke out when King died. People thought something bad was going to happen. Everybody gathered at my mother’s house to listen to the news reports. Mean, you just couldn’t believe it. They had the same reaction when Kennedy was shot. We stayed up all night and prayed that the man would live. We felt that we had lost a friend.”

A few months later, policemen walked into Nat Laws’ store.

“Are you the father of Joseph Laws,” they asked?

“Yeah?” Nat said.

“We’re sorry to report that your son is dead.”

Newspaper accounts said Joseph Laws committed suicide in a Reno jail cell on July 31, after being arrested on arson charges in connection with a number of grass fires in a middle-class Reno neighborhood. When jailed, Joseph was stripped of all clothing and his ankles were joined together on a short chain with one ankle connected by a two-foot length of chain to his bunk.

In his billfold was a military I.D. showing his discharge, which indicated some mental problems. Police had tried to have him admitted to a hospital, but the hospital’s policy would not allow him to be admitted.

Jail cell “suicides” always trouble black families, but Joseph’s death had a couple of twists that still haunt the Laws family.

First, police said Joseph killed himself by twisting his head and throat beneath the two-feet of chain that connected his foot to the bed, thereby cutting his throat, an act that would require a contortionist.

Second, by the time the family was notified of his death, Joseph had been dead and buried in a Reno veterans cemetery for nearly three months.

Nat: “I don’t believe he committed suicide. They were hiding something. Why did they bury him so fast? My son was raised Catholic. He was an altar boy. It would have gone against his religion.”

::

By the 1970s, a pattern of progress was beginning to emerge as blacks in Los Angeles began to reap the benefits of the civil rights struggles of the 1950s and 1960s. The 1973 election of Tom Bradley as mayor symbolized that change. And so did the gains of the third Laws generation.

In 1971, Nat’s son, Henry, a postal worker for 12 years, became a postal inspector, at the time a major breakthrough. Two years later, his brother, Phillip, became the first black field representative for a major insurance company.

Phillip: “I was one of three workmen’s compensation underwriters, handling about $10 million in insurance. That’s when I got introduced to corporate games, you know, stuff like cocktail parties, receptions, business lunches. I had an expense account and spent $200 a month on gas. My expense account ran $400, $500 a month, no questions asked. It was a mind blower. That was more money than I used to make. I left there and went to another firm where I was the first black marketing representative, and to another firm where I was a liability underwriter. I was trying to learn all I could because I wanted to start my own company. At each job, I always started out lower on the pay scale than the white boy, but it was big money to me.”

That year, while Alfred’s second daughter earned a junior college degree from Los Angeles Trade Technical School, Delores’ youngest son became the first member of the family to graduate from college. A year later, he became a postal inspector — attaining in one year what it had taken his cousin Henry, in less favorable times, 12 years to achieve.

In the midst of the Watergate summer, Leroy’s daughter, Marsha, and her husband received a Small Business Administration loan and bought a liquor store in Watts not far from where they completed high school.

Marsha: “It was very successful. By the time we sold it, we were grossing a half-million dollars a year. It was good money, but it was hard work and it was very depressing to see so little progress among many of the people in my old neighborhood. When I first went into business, I was like a social worker. The high school students couldn’t read, and couldn’t talk. Instead of them saying, ‘Give me one of those,’ they said, ‘Gimme one of dem.’ That hurt. It really hurt. They couldn’t read ‘Snickers’ on the candy bar wrapper. They would have to point. We would try to tell them the name. Finally, I had to tell my workers that that’s not our job: ‘They’ll get an inferiority complex and won’t come here.’ It’s cold, but that’s business.”

Some of the third generation, however, faltered along the way. One summer night in 1974, Alfred’s oldest son, Alfred Jr., and a friend robbed a store at 190th and Avalon and in the process shot the two proprietors. One died. The next year, Alfred, then 18, was found guilty of murder and sentenced to Soledad, where he remains.

By 1977, Nat’s son, Henry, had risen through the ranks of the post office with stints in Dallas and Memphis before finally being called to Washington, where he would work on a special project commissioned by President Jimmy Carter to reorganize federal agencies.

Leroy’s daughter, Marsh, and her husband had settled into a $240,000 home in Ladera Heights. Their son was taken out of public school and placed in an expensive academy also attended by the children of entertainers Burt Bacharach and Angie Dickinson and Dodger outfielder Pedro Guerrero.

Robert, Delores’ oldest son, who went to work for Southern California Edison after returning from Vietnam, was about to become one of two vice presidents for a construction firm. He had moved to a four-bedroom, tri-level home complete with swimming pool in a predominantly white neighborhood in Palo Alto. His brother, Anton, the postal inspector, had done likewise — swimming pool, four-bedroom, two-story home — in Rialto.

Robert: “There was a question when we moved in whether or not whites there wanted to live with blacks. After they got to know us, they didn’t have any problems. Association brings about an understanding. People get to know each other and they understand that we are not as bad as they thought we were. There are three black families in a neighborhood of 30 homes.”

By 1980, Leroy’s daughter, Marsha, and her husband had sold their liquor store. Henry had requested assignment in New York, and the family moved to a two-story Cape Cod home in Scotch Plains, N.J. Henry’s two daughters are in college, one studying journalism and the other majoring in urban planning. Alfred’s daughter, Donna, purchased a comfortable condominium in Compton and went into partnership in her own accounting firm. Angela, his oldest daughter, tends Anna Laws and manages a fast-food restaurant in Watts.

Anna Laws is now 94 years old. The stroke she suffered not long ago causes her memory to fade in and out. When she is lucid, she recalls clearly the advancements that have come from years of struggle.

“Lord, things have changed a lot,” she says feebly. “When I first came here, it was pitiful for colored people. We had such a rough, tough life, nothing like it is now.

“I’m very proud of my family. I tried to teach my children that it doesn’t hurt to work. They came out all right. Back then you wouldn’t have thought that you’d have the kind of luck with the children that we did.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.