Black San Diego has yet to establish sense of community

This story originally ran in 1982 as part of the “Black L.A.: Looking at Diversity” series. Please note: Our standards on certain terms have changed, but we have preserved the original text in order to provide an accurate account of the work in print.

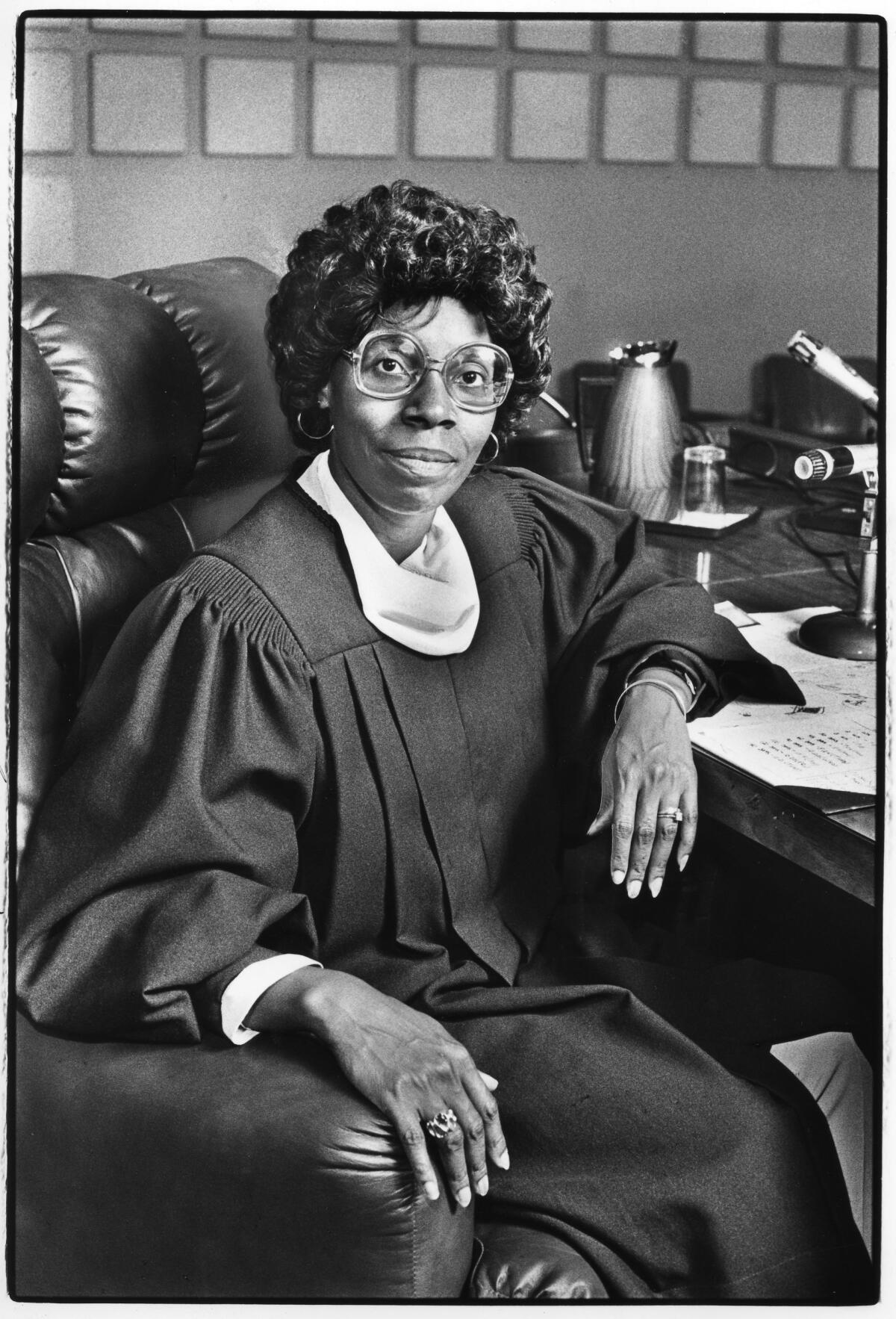

Although it happened almost two years ago, the incident stands out in Municipal Judge Elizabeth Riggs’ memory as “probably the most classic” example of racism she has encountered.

It involved a man brought into Riggs’ El Cajon court on a traffic ticket, not very long after her appointment as San Diego County’s first black woman judge. When his turn before the bench came, the man’s excuse for the infraction was: “It was raining so hard, it was raining pitchforks and nigger babies.”

“I finished listening to him and at first I didn’t think I heard right,” she recalled recently. “After he left, my bailiff came up and said, ‘Did he say what I thought he said?’”

Riggs is certain the man, who was white, didn’t intend to insult her — and, in fact, seemed oblivious to her color. But she believes that made it all the worse. “They have so long held us in disregard and looked down on us that we’re just the ‘invisible man,’” she said, referring to black writer Ralph Ellison’s classic novel of that title. “He just didn’t even see me.”

The incident is telling in more ways than one.

In many respects, San Diego County is like that scene in Riggs’ courtroom — a place of glaring contradictions for its small and diffuse black population.

Despite its emergence in recent decades as a major city in California and the nation, San Diego has fewer blacks than most other large metropolitan areas of the country, according to the federal Census Bureau. Up until about 40 years ago, it was virtually an all-white corner of the Southland, and even now blacks account for only 5.6% of the county’s 1.86 million residents and 8.9% of the city of San Diego’s population.

In the summer of 1982, The Times published a series on Southern California’s Black community called “Black L.A.: Looking at Diversity.”

By way of comparison, in the city of Dallas, whose population of 904,078 is closest in size to San Diego’s, blacks constitute 29.4%, while in Los Angeles, blacks make up 17% of the city’s 2.96 million residents.

But San Diego’s racial makeup is changing.

Census figures and interviews with black residents indicate that growing numbers of blacks are moving here, or inquiring about San Diego as a place to live and work.

Is San Diego a good place for blacks to be? The question elicits mixed opinions from black residents who see both potential and problems for the local black populace.

“I think it’s all economics. I think there just aren’t the opportunities here,” says Reese Jarrett, vice president of the Southeast Economic Development Corp., which hopes to attract new businesses to predominantly minority Southeast San Diego, thus generating jobs and housing.

‘Monocultural’ image

Some say San Diego’s slow pace, anemic social and cultural life, and conservative atmosphere are turnoffs for blacks, that the area has, as one community activist calls it, a kind of “monocultural” image.

Tom Johnson, a black administrator with Pacific Telephone, has found in his travels outside San Diego that to most blacks “it’s perceived as a kind of nice town for white folks to live in — and it’s perceived that way by whites, too.”

“It was a very small town up until recently, and a very prejudiced town,” says Charles Thomas, a black psychology professor at UC San Diego who has lived here 10 years. “You still hear people talk about knowing someone who has run into a snub at a store, at a restaurant, problems buying homes.”

Yet it is a place where the most senior San Diego city councilman, Leon Williams, won a solid victory in the June primary to become the first black elected to the county Board of Supervisors. The most influential figure in county government, aside from the five elected supervisors, is Chief Administrative Officer Clifford Graves, who also is black, as are the heads of the county probation, social services and health services departments.

And the number of black judges has increased from one (Earl B. Gilliam, now a federal judge) in 1976 to six.

San Diego is a place where, although they are outnumbered by Latinos, blacks have managed to hold onto a seat on the five-member city school board for 19 years. San Diego is the home base from which Clarence Pendleton, controversial former San Diego Urban League president, garnered the job of chairman of the U.S. Civil Rights Commission.

This is an area believed to have a higher percentage of black professionals than many major cities, a place where blacks hold key posts in nearly every field, from the military to private industry. “When you’re talking corporate and government position, your blackness is not the handicap that it might be elsewhere,” says the county’s Graves.

But in recent interviews with some 30 black San Diegans, The Times was told by several that such successes, combined with San Diego’s balmy weather and easygoing life style, tend to obscure the fact that there is trouble in “America’s Finest City” for its black residents.

“San Diego, despite its growth, is still very much a small town, and there are still power centers and social centers where blacks aren’t welcome,” says a prominent black public administrator. “There’s a saying that they let one [black] in, and if he dances better than they do, they don’t invite him back.”

Capt. Byron Wiley, 50, commander of recruit training at the Naval Training Center on Point Loma, observes: “I’ve been literally all over the world, certainly around the country, and of all the places I’ve seen, San Diego has the least bit of influence (held by) blacks of any place I’ve seen. Black people literally have no power — individually or collectively.”

In the political arena, some observers say, only “safe” blacks tend to be elected or appointed to public office, in part because of the area’s conservatism, and an election system that forces candidates for city offices to run citywide in general elections rather than by district. As a result, outspoken minority candidates can’t win, these observers believe.

“You’ve got to be acceptable to whites, there’s no question about it,” says Johnson, a longtime critic of the school district’s efforts to upgrade achievement levels of students in minority schools. Last year Johnson was passed over by the school board for appointment to a seat representing Southeast San Diego, in favor of moderate Dorothy Smith, despite the broad-based support he received from area community leaders and parents.

As in most major cities, black unemployment in San Diego is nearly twice the overall jobless rate for the county, according to state employment officials. The jobless rate for local black youths is estimated at upwards of 40%. Blacks with jobs complain regularly to the local National Assn. for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) chapter about job discrimination, says NAACP President Mamie Green, who estimates her office receives at least 25 calls a week.

Limited social scene

Even the social and cultural scene, although seen as improving, leaves much to be desired for blacks who want to party without feeling “out of place.” Some blacks even complain of feeling downright unwanted at some local cubs.

“If you look at some of the entertainment spots in San Diego that might have gone heavy disco, when they become heavily patronized by blacks then they (the owners) find another type of [music] programming that would discourage black patrons — either country and western or rock,” says Jarrett of the Southeast Economic Development Crop. “One wonders why that happens.”

When Bea Kemp, a local attorney, and her husband, Michael, recently entertained a black visitor from out of town, their first stop was the San Diego Hilton. The vocalist was black “and the music was nice, but there weren’t many black folks there,” Kemp recalls. Their next stop was the Black Frog, a black-owned restaurant and club that is the premier gathering spot for black professionals.

“That is not to say I feel uncomfortable with white people. ... It’s (the Black Frog’s) just the most comfortable setting for me,” Kemp says, likening her Hilton experience to how a man might feel at a baby shower.

Add to that the sky-high cost of housing and the dearth of the kind of industry that generates blue-collar jobs, and San Diego emits a subtle signal, some black residents say.

“If you’re listening close enough and long enough, the message is, ‘If you do not have any money, do not come to San Diego,’” says Makini Callahan of the Black Federation of San Diego, which provides social services to the disadvantaged. “This is basically a private community.”

The numbers tell much of the story.

Figures from the 1980 census show that during the 1970s, San Diego County’s black population grew 68.4%, from 62,028 to 104,452 — a dramatic rise when compared with an overall increase in the county population of 37.1%, and a 21% jump for whites.

But because the total population also has soared, in terms of percentages, the black presence has changed very little since 1970, when the county was 4.6% black and the City of San Diego 7.6%.

Second lowest percentage

In fact, census figures show that of the nation’s 10 most populous cities, only San Antonio, Texas, has a smaller percentage of blacks (7.3%) than San Diego with 8.9%.

And of the other eight largest cities, only Los Angeles has less than 20% black population. The other cities range from 25.2% in New York to 63.1% in Detroit.

The fact that San Diego’s black populace is so small is seen as both an asset and a liability for blacks.

When you have large concentrations ... of blacks, I think that we’re more visible and people are more aware of us. If they’re negative or prejudiced and want to put barriers in front of us, it’s easier,” noted Vera Landen, a newcomer from Tucson who is looking for a management consulting position.

“Here we can slide, we can go around the edges ... we can choose to highlight being black or downplay it,” she said. “We have that option here and a lot of other places we don’t.”

Clifford Graves agrees, but sees disadvantages as well. “The main problem blacks have here is that the percentage is so small that they don’t form any critical mass for social or political change,” he notes. “What’s been accomplished is largely the result of individuals ... breaking the color barrier and bringing a few people in with them.”

“It’s a dichotomy for me,” said Larry Marion, 53, a former Navy signalman who settled here in 1975 after leaving the service. He now runs a management consulting firm.

“If I were looking at a city where there was black visibility, where there were black activist kinds of things going on, San Diego would not be my choice,” he said. But that same void presents “a hell of a challenge” to those willing to work for progress, and “I couldn’t play golf all year round” most other places, Marion added.

::

If San Diego’s black population seems small today, it was almost non-existent nearly a century ago, when the 1880 census recorded three black residents.

Material on file at the San Diego Historical Society library indicates that the number of blacks grew as San Diego did — slowly, until World War II and the postwar period, when defense industry jobs expanded significantly. By 1940, blacks made up 2% of the city’s population, jumping to 4.5% in 1950 and 6% by 1960.

Historically, most blacks migrating from the South to the West chose larger cities like San Francisco or Los Angeles, with already established black communities, relatives, railroads, and heavy industry serving as “pull factors” to get them there.

“Until the middle 1880s, San Diego had been an anomaly, a white island, and this characteristic was a subject for comment in other parts of the United States,” Robert Lloyd Carlton wrote in a 1977 master’s thesis for San Diego State University on early black settlement here.

“People had always said, ‘Well, there’s one thing you won’t see when you get to San Diego, and that is colored people, because there aren’t any there!’” noted a woman quoted in Carlton’s study who came to San Diego from Topeka, Kan., in 1891 at age 11. Her first impressions were recalled in a 1958 interview.

“In Topeka, we lived close to what they called Tennessee Town, and we were used to colored people. When we got to San Diego the very first thing I saw when I got off the train was a big colored man with a white coat. That was a porter of course, but I was kind of disgusted with San Diego, to tell the truth, when the first thing I saw was a colored man ...”

::

Some say San Diego is a new frontier waiting to be explored, a land of opportunity for experienced black professionals and skilled technicians.

In general though, jobs — or the lack of them — are considered the biggest stumbling block for most blacks who come here.

One notable exception is the military, which is a major force in drawing and employing blacks here. Officials with the Navy and Marine Crops estimate the number of black enlisted personnel stationed in San Diego County at between 15,000 and 20,000. There is even a black rear admiral.

“Null, nil and void” is how the NAACP’s Green describes prospects for blue-collar employment in San Diego. Green, a job agent at the state Employment Development Department (EDD) office in Southeast San Diego, says the employment outlook for blacks in particular is “frightening” because of the way the local economy — based largely on tourism, agriculture and high technology, all fields that seem to employ few blacks — works against them.

Some local economic experts say blacks are being displaced by undocumented workers in lower-paying service jobs. That may explain the dearth of blacks working as waiters and in other jobs tied to San Diego’s hotel and restaurant industry. However, some black leaders say young people don’t want these jobs because of their menial nature.

The picture is discouraging. But there are signs that blacks are just as intrigued by San Diego’s famous good weather and growth opportunities as non-blacks, and the word is getting around. “Places like L.A. and San Francisco, things have been tried and accomplished by black folks,” says attorney Kemp. “There’s so many vistas here.”

Not too long ago, a young black Greyhound bus driver remarked over a drink at the Black Frog that he was thinking about moving from the San Francisco Bay Area to San Diego. The driver, a native San Diegan who moved away about 10 years ago, said the outlook for blacks no longer seems as bleak as it did when he was growing up here.

And Green talks about the phone calls she gets “from people from all over” asking about San Diego. “I’ve had calls from New York, from Chicago, from Boston — the other day a woman called from Oklahoma,” Green said. “She wanted to know was there a black community here.”

The question is not as silly as it may sound.

Green says many of the blacks she’s seen who have come here in search of jobs from places like Texas, Mississippi, Arkansas, Louisiana and Los Angeles “have wound up going back to where they came from,” not only because they can’t find work but because there is no “support system” to readily plug into.

In most major cities with large concentrations of blacks, the black community is such a system, a home of eating places, clubs and other businesses that cater to black consumers.

In San Diego, most whites and a number of blacks tend to think of that community as Southeast San Diego, mainly because sizable numbers of blacks have lived there since World War II.

But a close examination of census data shows that while it is, as Green tells callers, “a black pocket,” Southeast is not, as many see it, a monolithic Afro-American community. That’s something most longtime black San Diegans have known for years.

Earl Davis, editor of the local black weekly newspaper, the Voice News & Viewpoint, says: “Southeast San Diego is not primarily black. Folks don’t want to believe that, but it isn’t.”

In fact, in the Southeast area, as drawn on a 1980 census tract map prepared by the San Diego Assn. of Governments, whites make up 38.5% of its nearly 104,000 residents, compared with 35.4% black, 10.4% Asian and 15.7% “other” ethnic groups. Persons of Hispanic origin, who may fit into any one of those four groups, are 24.0% of the total Southeast population.

What that means is that only about 36,800 blacks live in Southeast San Diego — 35% of the county’s total black population. The City of San Diego has three-quarters of all the county’s blacks, but the remaining one-fourth live just about anywhere whites do — with significant concentrations in National City (9% black), Oceanside (7.5%) and Lemon Grove (4.7%).

The result is a diffused black community, and that is good, some say, because it indicates there is mobility for blacks if they can afford housing prices.

It’s a far cry from the days when Phil Rostodha, owner of a small tobacco shop off 5th Avenue in downtown San Diego, was a child. “We lived in a ghetto that was bounded by very rigid boundaries,” he recalls. “When I grew up it was a big deal for blacks to live east of 32nd Street, and it was a tremendous achievement for blacks to buy a place in Valencia Park,” now one of San Diego’s most-established middle-class black neighborhoods.

But that same dispersion makes it difficult for blacks to form the kind of voting bloc that could hand candidates of their choice victories in elections, and to develop a stronger economic base in the Southeast.

“Any other city you go to, as close as L.A. or as far away as Boston, black people have things we don’t have here,” says newspaperman Davis, a former General Dynamics engineer who has lived here since 1959. “They have black banks, black restaurants, insurance companies. ... Here we have, it seems, one of everything. It’s ridiculous.”

That does not mean the potential is not here.

On the contrary, nearly all of those interviewed by The Times believe that in many ways the potential is great — but the feeling is that, for whatever reason, that potential is being realized only by a handful of individuals.

“I can remember saying to myself just like everybody else ... ‘Boy, everything is so new here and you’ve got a chance to get in on the ground floor,’” Davis said. “That was 1959 and this is 23 years later, and black people are still saying that.”

But some say that if San Diego is not what it could be for blacks, it may be that they have themselves to blame.

Greg Akili, a community activist here during the late 1960s and early 1970s who is now an organizer for the San Diego-based United Domestic Workers union, says too many blacks have what he calls a “siege mentality” that tends to magnify problems like racism and perceived competition from Latinos and women.

“You always got to protect,” he said. “It doesn’t allow you to plan.”

Still others say San Diego’s black community tends to be cliquish and indifferent to newcomers of its race, and that, once established, too many blacks become complacent with their success.

NAACP President Green says: “Some of us have a tendency to feel that what is happening to John Henry across the street who does not have the luxury of a nice home, a luxury car or money in the bank does not affect them.”

But there are signs that that too is changing.

Green points to the emergence of new organizations like the Forum and the Black Leadership Council, with memberships made up of a broad cross section of blacks who are beginning to address longstanding social concerns and to develop ways for blacks to benefit from San Diego, economically and politically.

For example, the Forum, a year-old “networking” organization of black professionals in both public and private sectors, recently sent its members a fact sheet on a proposed psychiatric hospital in Southeast, with a cover letter urging them to make their opinions — pro or con — known to the media and elected officials.

Just last month, the Black Leadership Council of San Diego, whose 26 members include representatives of most local black organizations, held a conference designed to develop strategies to deal with a broad range of problems affecting the black community, from police harassment to education of youngsters.

And for those who have long complained that San Diego’s social scene leaves a lot of be desired for unattached blacks, there is now a black singles club. Actress Alyce Cooper notes that black theater and arts, once “like a caterpillar in a cocoon,” are on the verge of blossoming, with three black drama companies as well as all-black productions being staged by the San Diego Repertory Theatre.

Put bluntly, William Jones, a top aide to City Councilman Williams, is bullish on San Diego for blacks.

“My optimism is relative to what I sense blacks are encountering in other major cities — large-scale despair, hopelessness, blacks tied into the ghetto with no hope of ever getting out ... permanent under-class citizenship,” he says. “You don’t see blacks living in the ghetto [here] as compared to a Watts or a Harlem.

“For the most part, I don’t think blacks in San Diego feel their fate will be second-class citizenship because there’s potential, there’s opportunity. It’s a frontier for those who know how to pioneer.”

Union leader Akili echoes: “Blacks here talk about ‘Man, blacks really got it together in Chicago’ or someplace else. To be honest, I have not seen these things other people are talking about. ... No matter what they’ve seen elsewhere, you’ve still got nice weather, it’s a fairly clean environment and it’s not threatening.

“I see more and more [blacks] coming here and you have to ask yourself why — why if it’s such a dead town. This is really a nice place to be.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.