Is it time for us to hit ‘reset’?

Extra Lives

Why Video Games Matter

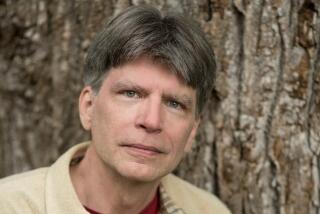

Tom Bissell

Pantheon: 222 pp., $22.95

Extra Lives

Why Video Games Matter

Tom Bissell

Pantheon: 222 pp., $22.95

To many of its admirers — and skeptics — the video game seems a medium in adolescence. Caught between minor and major status, and constantly springing new parts, it’s still figuring out what it is and where it belongs. Some commentators, like optimistic parents, hope for greatness: A contributor to a Slate podcast last winter ventured that the video game may be “akin to what film was a hundred years ago.” Last year, the London Review of Books ran an essay on the video game called simply “Is It Art?” (The answer was a qualified “yes.”) For now, no one quite knows whether it is an art form or, indeed, just a game.

Variants of the question — as problematic as it is alluring, since it implies certainty as to the nature of art itself — haunt Tom Bissell’s “Extra Lives: Why Video Games Matter.” This journalistic memoir is not only about the meaning of video games; it’s about the heat and hesitation of love.

As Bissell writes after playing the zombie-centric Left 4 Dead: “All the emotions I felt during those few moments — fear, doubt, resolve, and finally courage — were as intensely vivid as any I have felt while reading a novel or watching a film or listening to a piece of music. For what more can one ask? What more could one want?” But soon after, he considers the nature of fellow video game fans whom he meets in a gaming store. “I then realized I was contrasting my aesthetic sensitivity to that of some teenagers about a game that concerns itself with shooting as many zombies as possible. It is moments like this that can make it so dispiritingly difficult to care about video games.” Like a chat with a smart friend who may have fallen for a ditz, “Extra Lives” provides a lesson in articulate ambivalence.

Bissell owes some of his quarrel to the video game’s issue with narrative. In the role-playing games he takes for his subject, participants can design their avatars’ personalities, appearances, species and more. (During a recent spell of Dragon Age, for example, I elected to be a dexterous elf with pillowy lips.) Such games usually provide pre-filmed scenes that establish facts of the story. Within those bounds, your avatar can perform a variety of activities: save her brethren’s lives, seek her missing sword or — depending on the freedom the game permits, and on her level of integrity — ignore the predetermined plot and gallivant in the forest while, in a nearby village, a winged beast slays her family. For Bissell, who writes fiction as well as journalism, and for other gamers who care about narrative consistency, such liberty can present problems.

And so — undertaking his quest for answers — Bissell spends much of the book interviewing members of the gaming community about the unstable alliance of stories and games. According to game designer Clint Hocking, the “very nature of drama, as we understand it, is authored,” but after a player seizes control, “pacing and flow and rhythm — all these things that are important to maintaining the emotional impact of narrative — go all willy-nilly.” In questioning where games fit into the artistic landscape, the sharpest commentators — Bissell included — reveal society’s long-held assumptions about story, character, theme and authorship.

As for the narrative of “Extra Lives,” it feels at once enchanting and labyrinthine, like a primeval wood. Throughout the book, Bissell’s game as a memoirist tends toward peek-a-boo rather than show-and-tell: He repeatedly refers to an unexplained trauma he experienced in Uzbekistan (for the curious, “Chasing the Sea,” Bissell’s admirable account of travel through central Asia, offers full elucidation).

And while he explains, as he puts it, “why I believe video games matter — and why they do not matter more,” his ambivalence can grow tiring, and his analyses can tilt toward contradiction. One might wonder why this form, if it doesn’t matter more, warrants such prolonged consideration. One wonders, too, how a writer capable of apt, inventive metaphor (the game industry “guards its secrets as guilelessly as a boy might hide from his mother — but not from his brother and sister — the extraterrestrial living in his bedroom”) can come up with comparisons as mysterious as this one: “Two of my three morning conversations had been like standing at the mouth of a cave filled with a three-hundred-year-old stash of whiskey, boar meat, and cigarettes.”

But love has driven people to more extreme gestures. (Think “Anna Karenina.”) In the end, one remembers the passion, and passion provides this volume with many enlightening and expansive moments. Here Hocking wonders if the odd bedfellows of game and story will someday find chemistry: “The question is, can we go … to completely different realms, using tools that are inherent to games? To let the player play the story, tell his own story, and have that story be deep and meaningful?” Hocking doesn’t know, and neither does Bissell. Their uncertainty feels thrilling, testifying to a sense of possibility — and of risk — alien to more established creative forms.

The book’s final chapter explores not only the nature of games, but also the nature of Bissell. He writes that he started playing the game Grand Theft Auto IV at the same time that he started using cocaine. His first drug-fueled joyride lasted 30 hours. He no longer uses the drug, but he plays video games constantly, preferring them to the books that were once central to his life. Now, he writes, he finds that “the pleasures of literary connection seem leftover and familiar”; now that games have overtaken his once-bookish existence, he has “no firm memory of who, or what, I once was.” Perhaps Bissell has suffered a grand theft of his own: a loss of his previous life in favor of the “extra lives” onscreen. His love has proven dangerously intoxicating.

Deutsch is a writer from New York. Her work appears in the Village Voice, Bookforum, n+1, Poetry and other publications.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.