How the rap war began

SEE CORRECTION APPENDED: “The Times apologizes over article on rapper”

--

SEE UNPUBLISHED CORRECTION BELOW:

A March 19 article on Page E-1, Calendar (“How the rap war began”), incorrectly stated that rap star Tupac Shakur’s posthumously released album “The Don Killuminati” sold 800,000 copies in its first week. According to Nielsen SoundScan, 664,000 copies were sold in the first week

--

NEW YORK -- Cameras flashed as paramedics carried the victim into the glare of Times Square on a stretcher. Blood seeped through bandages from five gunshot wounds.

Tupac Shakur had been beaten, shot and left for dead at the Quad Recording Studios on New York’s 7th Avenue. As he was borne to a waiting ambulance through a swarm of paparazzi on Nov. 30, 1994, the rap star thrust his middle finger into the air.

It was a portentous moment in hip-hop -- the start of a bicoastal war that would culminate years later in the killings of Shakur and rap’s other leading star, Christopher Wallace, better known as the Notorious B.I.G.

The ambush at the Quad remains a source of fascination and frustration to music fans and law enforcement officials alike. No one has ever been charged in the attack.

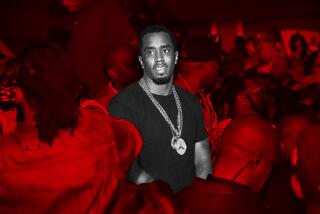

Now, newly discovered information, including interviews with people who were at the studio that night, lends credence to Shakur’s insistence that associates of rap impresario Sean “Diddy” Combs were behind the assault. Their alleged motives: to punish Shakur for disrespecting them and rejecting their business overtures and, not incidentally, to curry favor with Combs.

The information focuses on two New York hip-hop figures -- James “Jimmy Henchman” Rosemond, now a top talent manager, and promoter James Sabatino, now in prison for unrelated crimes.

FBI records obtained recently by The Times say that a confidential informant told authorities in 2002 that Rosemond and Sabatino “set up the rapper Tupac Shakur to get shot at Quad Studios.”

The records -- summaries of FBI interviews with the informant conducted in July and December 2002 -- provide details of how Shakur was lured to the studio and ambushed. Others with knowledge of the incident corroborated the informant’s account in interviews with The Times and gave additional details. They spoke on condition that their names not be published.

According to this information, Rosemond and Sabatino enticed Shakur to the Quad by offering him $7,000 to provide a vocal track for a rap recording.

Three assailants -- reputedly friends of Rosemond -- were lying in wait. They were on orders to beat Shakur but not kill him and to make the incident look like a robbery, the sources said.

Sabatino informed Combs and Wallace in advance that a trap had been laid for Shakur, the sources said.

Rosemond, who has served prison time for drug dealing and weapons offenses, has been described by Vibe magazine as “one of the most respected and feared players in hip-hop.” His Czar Entertainment represents rappers Shyne, Too Short, Gucci Mane and the Game.

Rosemond has long denied any role in the Quad incident. He declined to be interviewed. In a statement he issued Monday, after a version of this article appeared on The Times’ website, Rosemond dismissed the new information as “garbage” and “a fabrication.”

“In the past 14 years, I have not even been questioned by law enforcement with regard to the assault of Tupac Shakur, let alone brought up on charges,” the statement said.

His lawyer, Jeffrey Lichtman, said Rosemond “was not involved in the assault and will not be prosecuted for it.”

Sabatino declined to comment.

Combs, whose business empire includes Bad Boy Records and clothing and fragrance lines, also declined to be interviewed. In a statement, he said the new information was “a lie,” “beyond ridiculous and completely false.”

The statement said that neither Combs nor Wallace “had any knowledge of any attack before, during or after it happened.”

--

Roots of an ambush

The Quad ambush had its roots in events a year earlier, when the Brooklyn-born Shakur, then 22, returned to New York from California to film the movie “Above the Rim.”

He befriended Rosemond, the son of Haitian immigrants, who had run with Brooklyn street gangs and worked in the crack trade before gravitating to the hip-hop scene.

According to accounts given by the two men and others over the years, Rosemond, then 29, took Shakur under his wing, showing him around the city and introducing him to friends, including an ex-convict named Jacques “Haitian Jack” Agnant. Shakur and Agnant hit it off and were soon partying at clubs across Manhattan.

There was a serious side to the revelry. Rosemond was trying to establish himself as a talent manager, and he and Agnant hoped to represent Shakur. They encouraged the rapper to sign a recording contract with Combs’ fledgling Bad Boy label, which had recently received more than $2 million in capital from BMG’s Arista division.

Shakur also became acquainted with Sabatino, a 19-year-old Italian American who co-promoted rap conventions with Rosemond. Sabatino had Brooklyn roots of a different kind: His father was a captain in the Colombo crime family, according to federal authorities.

Like Rosemond and Agnant, Sabatino wanted to ride Combs’ rising star, and he too leaned on Shakur to leave Interscope Records and sign with Bad Boy.

Shakur rejected these overtures. Members of Combs’ circle saw this as an act of disrespect.

Shakur’s behavior in New York grew increasingly provocative. He insulted music executives and gangsters alike. He brandished weapons in public. Even friends thought he was out of control.

In November 1993, Shakur, Agnant and two other men were arrested on charges of gang-raping a 19-year-old fan at the Parker Meridien Hotel in midtown Manhattan.

A year later, Shakur was back in New York to stand trial on the charges. By then, his former pals were laying plans to exact revenge, according to the FBI informant and the other sources.

--

Carefully laid plans

On Nov. 29, 1994, two dozen Bad Boy executives and associates gathered on the 10th floor of the Quad to record songs for a debut album by Junior M.A.F.I.A. On hand, among others, were Combs, Notorious B.I.G., Rosemond, Agnant and Sabatino.

Rosemond had booked an adjacent studio to produce a recording by rapper Little Shawn, whose career he managed. This was the session at which Shakur was to be paid $7,000 for a guest vocal.

In fact, Rosemond never intended to record the session, according to the FBI informant and the other sources.

He had enlisted a trio of his friends from Brooklyn to ambush Shakur in the lobby of the Quad, the sources said. Agnant and Sabatino helped plan the attack, working out the timing, arranging for the three assailants to be driven to the studio and mapping out their escape route, according to the informant and the other sources.

Shakur’s friend Randy “Stretch” Walker was in on the plan, the sources said. In the hours before the attack, Shakur and Rosemond argued several times over the phone about how much Shakur would be paid. After the dispute was settled, Walker notified Agnant when Shakur was en route to the studio, the sources said.

Around 11:45 p.m., the lobby security guard was called away from his post, and the three assailants, dressed in army fatigues, moved into position. One sat in the guard’s chair. The two others waited outside.

Just after midnight, Shakur walked in with Walker and his manager, Fred Moore. As the rapper and his crew moved toward the elevator, the assailants confronted them and demanded their jewelry. When Shakur refused, the attackers began to pistol-whip him.

The rapper surprised them by drawing his own weapon. Gunfire erupted, and Shakur accidentally shot himself in the groin. The assailants shot Shakur four times. He sustained injuries to the head, hand and thigh. The men beat and kicked Shakur as he lay bleeding on the ground. Then, ripping a $40,000 gold medallion and chain from his neck, they escaped into the night.

Moore, who was also wounded, gave chase and collapsed in the street.

Shakur managed to limp into the elevator and push the button for the 10th floor. When the elevator doors opened, the rapper surveyed the assembled Bad Boy crowd.

In a 2005 interview with Vibe magazine, in which he denied any role in the attack, Rosemond described how the injured Shakur accused him of being in on the ambush.

Rosemond quoted the rapper as asking: “Why you let them know I’m coming here? You was the only [one] who knew, man. Why?”

In a bizarre twist, Shakur, bleeding badly, sat on a couch and rolled a joint, witnesses said. Police and paramedics, alerted by a 911 call, showed up minutes later. Shakur was taken to Bellevue Hospital Center.

The FBI informant said Agnant “seemed mad that Shakur was still alive and kept calling” the hospital “to check on Shakur’s status.”

Efforts to reach Agnant for comment were unsuccessful.

The very next day -- Dec. 1, 1994 -- a heavily bandaged Shakur rolled into court in a wheelchair to hear the jury’s verdict in the Parker Meridien case. He was convicted of first-degree sexual abuse and later sentenced to 4 1/2 years in prison. Shakur served part of the sentence before being freed on bond while he appealed the verdict. (Agnant had pleaded guilty to misdemeanor charges and avoided prison.)

The three men identified by the sources as Shakur’s assailants are all serving time in federal penitentiaries for unrelated crimes. The Times is withholding their names because they have not been charged.

In correspondence with The Times, one of the men said that Rosemond orchestrated the ambush. Another was cryptic. He wrote that the statute of limitations for the assault had expired, and he offered to produce, for an unspecified fee, the medallion stolen from Shakur.

The third inmate denied involvement in the attack.

--

‘Bad Boy’s behind this’

The Quad ambush triggered a vicious feud between East Coast and West Coast rappers and their record labels, New York-based Bad Boy and Los Angeles-based Death Row Records, where Shakur signed.

In April 1995, Vibe magazine published a prison interview with Shakur in which he said Combs and his associates were responsible for the attack. Not long after, Bad Boy released a song by the Notorious B.I.G., “Who Shot Ya?,” which closes with a taunt:

“You rewind this

“Bad Boy’s behind this.”

In June of that year, Death Row founder Marion “Suge” Knight mocked Combs onstage during a rap awards show in Manhattan. Two months later, Knight’s bodyguard was shot and killed at a club in Atlanta; no one was ever charged.

In November 1995 -- a year to the day after the Quad ambush -- Shakur’s onetime companion, “Stretch” Walker, was shot dead in Queens, N.Y.

The following year, in the song “Hit ‘Em Up,” Shakur belittled Combs, bragged that he had sex with B.I.G.’s wife and vowed retribution for the Quad assault.

On Sept. 7, 1996, Shakur was fatally wounded in a drive-by shooting on the Las Vegas Strip. Six months later, the Notorious B.I.G. was shot dead in Los Angeles, also in a drive-by. No one has been charged in either slaying.

In the years after the mayhem at the Quad, Rosemond tried to dispel persistent rumors that he arranged the attack. He protested his innocence in Vibe magazine and appealed to Shakur, in vain, to cease his public accusations.

The New York police investigation into the attack quickly hit a dead end. But federal prosecutors conducting a broad investigation of the rap business have continued to explore the incident. Music industry figures have been called before a federal grand jury and questioned about what happened that night.

--

‘Set me up’

Two months after Shakur was killed, his album “The Don Killuminati” entered the pop charts at No. 1 and sold 800,000 copies in its first week. In the song “Against All Odds,” Shakur, like a ghost from the grave, calls out those he held responsible for starting the violence:

“Puffy [one of Combs’ nicknames], let’s be honest, you a punk. . . .

“You can tell the people you roll with whatever you want

“But you and I know

“What’s goin’ on.”

Shakur then mentions “a snitch named Haitian Jack” and promises “a payback” to “Jimmy Henchman in due time.”

“Set me up, wet me up. . . . stuck me up,” he sings.

“But you tricks never shut me up.”

--

---

START OF APPENDED CORRECTION:

“The Times apologizes over article on rapper”

---

Los Angeles Times

Thursday, March 27, 2008

The Times apologizes over article on rapper

Home Edition, Main News, Page A-1

Metro Desk

38 inches; 1579 words

--- START OF CORRECTION ---

For The Record

Los Angeles Times Friday, March 28, 2008

Home Edition Main News Part A Page 2 National Desk

1 inches; 42 words

Type of Material: Correction

Tupac Shakur: An article in Thursday’s Section A on The

Times’ plan to investigate its March 17 report on rapper Tupac Shakur

gave the wrong first name for the lawyer for rap talent manager James

Rosemond. He is Jeffrey Lichtman, not Marc.

--- END OF CORRECTION ---

By James Rainey, Times Staff Writer

A Los Angeles Times story about a brutal 1994 attack on rap superstar Tupac Shakur was partially based on documents that appear to have been fabricated, the reporter and editor responsible for the story said Wednesday.

Reporter Chuck Philips and his supervisor, Deputy Managing Editor Marc Duvoisin, issued statements of apology Wednesday afternoon. The statements came after The Times took withering criticism for the Shakur article, which appeared on latimes.com last week and two days later in the paper’s Calendar section.

The criticism came first from The Smoking Gun website, which said the newspaper had been the victim of a hoax, and then from subjects of the story, who said they had been defamed.

“In relying on documents that I now believe were fake, I failed to do my job,” Philips said in a statement Wednesday. “I’m sorry.”

In his statement, Duvoisin added: “We should not have let ourselves be fooled. That we were is as much my fault as Chuck’s. I deeply regret that we let our readers down.”

Times Editor Russ Stanton announced that the newspaper would launch an internal review of the documents and the reporting surrounding the story. Stanton said he took the criticisms of the March 17 report “very seriously.”

“We published this story with the sincere belief that the documents were genuine, but our good intentions are beside the point,” Stanton said in a statement.

“The bottom line is that the documents we relied on should not have been used. We apologize both to our readers and to those referenced in the documents and, as a result, in the story. We are continuing to investigate this matter and will fulfill our journalistic responsibility for critical self-examination.”

The story first appeared March 17 on latimes.com under the headline “An Attack on Tupac Shakur Launched a Hip-Hop War.” The article described a Nov. 30, 1994, ambush at Quad Recording Studios in New York, where the rap singer was pistol-whipped and shot several times by three men. No one has been charged in the crime, but before his death two years later, Shakur said repeatedly that he suspected allies of rap impresario Sean “Diddy” Combs.

The assault touched off a bicoastal war between Shakur and fellow adherents of West Coast rap and their East Coast rivals, most famously represented by Christopher Wallace, better known as Notorious B.I.G. Both Shakur and Wallace ultimately died violently.

The Times story said the paper had obtained “FBI records” in which a confidential informant accused two men of helping to set up the attack on Shakur -- James Rosemond, a prominent rap talent manager, and James Sabatino, identified in the story as a promoter. The story said the two allegedly wanted to curry favor with Combs and believed Shakur had disrespected them.

The purported FBI records are the documents Philips and Duvoisin now believe were faked.

The story provoked vehement denials from lawyers for Combs and Rosemond, both before and after publication.

Rosemond said in a statement Wednesday that the Times article created “a potentially violent climate in the hip-hop community.” His attorney, Marc Lichtman, added: “I would suggest to Mr. Philips and his editors that they immediately print an apology and take out their checkbooks -- or brace themselves for an epic lawsuit.”

Although The Times has not identified the source of the purported FBI reports, The Smoking Gun (www.the smokinggun.com) asserted that the documents were forged by Sabatino. The website identified him as a convicted con man with a history of elaborate fantasies designed to exaggerate his place in the rap music firmament. He is currently in federal prison on fraud charges.

“The Times appears to have been hoaxed by an imprisoned con man and accomplished document forger, an audacious swindler who has created a fantasy world in which he managed hip-hop luminaries,” the Smoking Gun reported.

Combs’ lawyer Howard Weitzman, in a letter to Times Publisher David Hiller, called the story inaccurate. He expanded an earlier demand for a retraction and said he believed that The Times’ conduct met the legal standard for “actual malice,” which would allow a public figure such as Combs to obtain damages in a libel suit.

The purported FBI reports were filed by Sabatino with a federal court in Miami four months ago in connection with a lawsuit against Combs in which he claimed he was never paid for rap recordings in which he said he was involved. Sabatino, 31, said he had obtained the documents to help him prepare his defense in a criminal case against him in 2002, according to the Smoking Gun.

Philips, a Pulitzer Prize-winning reporter, said he believed in the authenticity of the documents in part because they had been filed in court. But the Smoking Gun’s sharply critical review said The Times had overlooked numerous misspellings and unusual acronyms and redactions that could have cast doubt on the documents’ authenticity.

Moreover, the documents appeared to have been prepared on a typewriter, the Smoking Gun account noted, adding that a former FBI supervisor estimated that the bureau ceased using typewriters about 30 years ago. The website said its reporters had learned that the documents could not be found in an FBI database.

The website also described unexplained coincidences that made it appear Sabatino had composed the documents from prison. The Smoking Gun showed that Sabatino had filed court papers on his own behalf that had “obvious similarities” in typography and “remarkably similar spelling deficiencies” to those in the purported FBI documents.

The Smoking Gun used a report from Sabatino’s sentencing in 2003 for fraud and identity theft to suggest that his history of lying began in childhood. When the boy’s mother left home at 11, he told a teacher that his mother had died in an accident, rather than acknowledge the truth, said his father, Peter Sabatino, according to the website. It posted what it said was a letter that the father wrote to the judge.

At the sentencing, the younger Sabatino told the judge that he had been battling a “demon for a very long time” and that his motivation for committing fraud was “to make attention to myself,” according to another court document posted by the website. The headline on the Smoking Gun story, over a picture of the picture of the portly Sabatino: “Big Phat Liar.”

Philips said in an interview that he had believed the documents were legitimate because, in the reporting he had already done on the story, he had heard many of the same details.

He said a source had led him to three prison inmates who purportedly carried out the attack on Shakur. One of those inmates implicated the planners of the attack and another implied who was involved, Philips said. Two others who said they witnessed the attack corroborated portions of the scenario described in the article, he said. None of the sources were named in the story.

Philips also said the events the sources described fit with previous accounts in the media and even in Shakur’s songs.

Still, Philips said he wished he had done more.

Philips said he sought to check the authenticity of the documents with the U.S. attorney’s office in New York, which had handled the investigation of the attack on Shakur, and with a retired FBI agent, but did not directly ask the FBI about them. The U.S. attorney’s office declined to comment, while the former FBI agent said the documents appeared legitimate, Philips said.

His statement said he “approached this article the same way I’ve approached every article I’ve ever written: in pursuit of the truth. I now believe the truth here is that I got duped. For this, I take full responsibility and I apologize.”

Philips has spent years digging into the rap music business and had won a reputation as a dogged streetwise reporter. He and Times reporter Michael Hiltzik shared a Pulitzer Prize in 1999 for beat reporting for their accounts of entertainment industry corruption, including illegal detoxification programs for celebrities.

Duvoisin has overseen many of The Times’ most notable investigative projects in recent years.

The first significant tip that led to the Shakur story came nearly a year ago, Philips said. He conducted interviews and reported the story in the interim, then focused on the piece more intensively beginning in January.

The story was reviewed by Duvoisin and two editors on the copy desk.

Other investigative stories published by The Times in recent years have in some cases received the scrutiny of at least one more editor and often of the managing editor or editor of the newspaper. The Shakur piece did not receive that many layers of review.

Bob Steele, a journalism values scholar at the Poynter Institute, said he would not pass judgment on The Times’ editing process.

“But any time you have a substantive investigative project you need multiple levels of quality control,” Steele said. “You need contrarians within the organization who are going to be very skeptical.”

The editor of Smoking Gun, Bill Bastone, who shepherded the website’s critique, had been an acquaintance of Philips before the Shakur investigation. The two met not long ago for lunch, discussing their mutual passion for investigative reporting and other matters.

Bastone knew The Times would publish a story related to the attack on Shakur, and he said he had immediate misgivings when he saw the piece last week.

He said he called Philips to say “things just don’t feel right about this.”

Bastone said he “took no joy in doing this,” adding, “We greatly respect your paper and Chuck and Chuck’s work. . . . But I think what happened here is that this guy Sabatino is a master con man, and they got caught up with him.”

--

--

END OF APPENDED CORRECTION:

“The Times apologizes over article on rapper”

--

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.