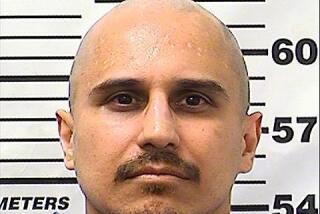

Man who spent 19 years in prison is seeking compensation for time lost

SACRAMENTO — DeWayne McKinney spent 19 years behind bars on a first-degree murder conviction before the recanting of eyewitnesses and confession of another inmate led to his release six years ago. What he never got, however, was an official ruling that he is an innocent man.

McKinney stands to win about $700,000 -- or $100 for each day he spent in prison -- if he prevails this week in a hearing before the state’s Victim Compensation and Government Claims Board. He must prove to the board that he is not the man who vaulted the counter of a Chapman Avenue Burger King in Orange during a Dec. 11, 1980, robbery and put a .22-caliber hollow-point bullet in the head of the night manager, 19-year-old Walter Bell.

Yet McKinney, who at 46 now runs an ATM business in Hawaii, said winning the case is not about money, but vindication.

“They’re saying I’m responsible. There’s a stigma,” McKinney said in an interview. “This is something that’s hanging over my head. A certain part of you can’t move on.”

The state attorney general’s office is fighting his compensation claim, arguing that although two of the four witnesses who implicated him at trial have since recanted, the other two remain convinced of his guilt.

“The evidence certainly seems to suggest that he was indeed the Burger King killer,” the attorney general’s office has argued in papers filed with the compensation board.

Expected to testify today on McKinney’s behalf is Orange County Dist. Atty. Tony Rackauckas, who prosecuted him personally in 1982 -- and unsuccessfully argued for the death penalty -- but in 2000 called for his release because there was enough evidence “to undermine confidence” in the conviction.

It is unclear how far Rackauckas will go in his support, however. He has said that he remained unsure whether McKinney was innocent or guilty. Still, McKinney’s lawyers say they are ready to introduce statements of two district attorney investigators who examined McKinney’s case and concluded he was innocent.

Taking the stand to testify Tuesday, McKinney had a soft voice and retiring manner. He said that he “wandered the street” after his mother died when he was 12 and within two or three years had found a second family in the 52nd Street Crips. He acknowledged breaking into cars and participating in an attempted jewelry store robbery.

About a month before the Burger King murder, McKinney testified, he suffered a shotgun wound to the right leg -- apparently from a rival gangster -- that left him hospitalized and on crutches. His lawyers argue that rules him out as the killer, whom witnesses said vaulted the restaurant counter.

Asked to display his wound at the hearing, McKinney lifted his pant leg to show a calf that remained visibly deformed 27 years later. McKinney, who maintained he was at his sister’s house during the robbery, said that going to trial for a murder he didn’t commit felt “surreal.”

“It’s almost like watching a movie or something,” he said.

McKinney, who was 20 and living in Ontario at the time of his arrest, said he entered lockup with a hot temper and a “self-destructive” streak. Within his first few months at the Orange County Jail, he said, guards forced him and other black inmates to share cells with Latinos, prompting a defiant lieutenant in the Mexican Mafia prison gang to attack him. When he bested the man in a fight, McKinney said, he found himself a marked man for years and was stabbed three times -- at the Orange County Jail and at the state prisons in Chino and Folsom -- and assaulted more times than he could count.

McKinney said that while in protective custody at the Orange County Jail, he met inmate Charles Hill, who claimed to have planned the Burger King robbery, along with his cousin Willie C. Walker and another man who was never charged with the crime. Hill said he backed out, but the other men went through with it and that the shooter later admitted to killing the restaurant manager.

Though McKinney alerted his public defenders, they questioned Hill’s story and could not get Walker to confirm the story. It would not be until 1997 that Hill, then an inmate at Lancaster State Prison, came forward with a letter again detailing his claims. The letter prompted investigations by the public defender’s office and the district attorney’s office that led to McKinney’s release in January 2000. Walker confessed to being the getaway driver and said that McKinney was not involved.

Testifying Tuesday, McKinney said he did not press Hill to come forward sooner because he believed Hill would have to do it in his own time. “I couldn’t twist his arm,” McKinney said. “I could cry and scream, and he could say no.”

Asked how incarceration affected him, McKinney said that being ordered around by guards for two decades has made him hypersensitive to any hint that he is being controlled.

“I’ve walked the tightrope between sanity and insanity,” McKinney said over a cafeteria lunch. “I can understand homeless people walking the streets. You can just let go.”

Walking on the streets, he said, he still eyes people as potential attackers and clenches up defensively as they pass, a survival lesson learned behind bars. He said he remains guarded around people he’s closest to. “I don’t think I’ll ever be normal,” he said.

During his cross-examination of McKinney, Deputy Atty. Gen. Michael Farrell forced McKinney to acknowledge his past as “Crazy DeWayne,” the gangster once convicted of attempting to rob a jewelry store in Glendora. He also elicited McKinney’s testimony about a time, at age 14, he chased a woman with a knife. Farrell also implied that it was an implausible coincidence that McKinney should just happen to run into Hill, the man who would help exonerate him, in the same protective custody unit at the same Orange County Jail.

In papers filed with the board, the attorney general’s office has argued that Hill and Walker -- described as “violent serial rapists” who are serving life behind bars -- concocted the story of McKinney’s innocence in the hopes of earning reduced sentences. The office argues that Hill considers McKinney “a brother,” giving him a further motive to lie for him.

To prevail at the hearing, which is expected to run through Thursday, McKinney must prove that it’s more likely than not that he did not commit the crime. The single hearing officer presiding over the case, Kyle Hedum, will make a recommendation to the victim compensation board, which will decide whether to grant McKinney’s request.

In 2001, a California law went into effect allowing the wrongfully incarcerated to claim $100 a day for each day spent behind bars after conviction. Since then, 17 people have filed claims with the Victim Compensation and Government Claims Board, according to statistics kept by the board, and eight have been successful, with awards ranging from $17,200 to $756,900.

Board spokesman Miles Bristow said that he knew of no case in which a claimant had prevailed over opposition from the attorney general’s office.

*

christopher.goffard @latimes.com

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.