James Tenney, 72; Bold Experimenter in Musical Sounds

Experimental composer James Tenney -- whose music consistently broke new ground through his fancy for startling sounds and his novel approaches to pitch, harmony and form -- died Aug. 24 in Valencia. He was 72 and the cause of death, according to his wife, Lauren Pratt, was cancer.

Tenney was as close to experimental music royalty as a modern composer could get, having studied or worked with a host of famed American mavericks, including Harry Partch, Edgard Varese, Carl Ruggles and John Cage. He was in on the seminal musical developments of the 1960s: the founding of computer music and Minimalism, the revivals of Charles Ives’ music and of ragtime. He participated in the Cage-inspired art movement Fluxus.

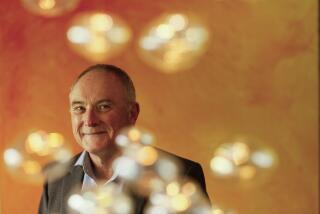

A noted musical theorist, virtuoso pianist and professor at CalArts, he was also an archetype of the ruggedly individual American artist. He spent the bulk of his career in cosmopolitan centers, where he worked and taught at high-powered institutions in New York, Toronto and Southern California. But having grown up in New Mexico, he favored informal Western clothes and set off his grizzled face with a goatee.

To some extent, he was the ultimate Western composer. He approached each new piece as an adventure, with the goal of discovering original territory and, if need be, taming some theoretical musical beast or acoustical bugbear.

In one of his best-known scores, “Having Never Written a Note for Percussion,” he drew a single note on a postcard. He asked that the note, of no specified pitch, last a long time. It begins at the threshold of hearing, rises in volume to the threshold of pain and returns to near-silence. But the sound can prove astonishingly complex and the effect on a listener is memorable. No instrument is indicated, but if, say, a cymbal is used, the textures grow so thick that the ear becomes all but overwhelmed by their richness and volume.

Tenney was equally the master of the other extreme, writing music that appeared extremely intricate on the page and was terrifically difficult to play. He was not afraid to ask musicians to tune to complex fractions of the normal pitches in the 12-note temperament. The surprise is that even the untrained ear can immediately comprehend the bracing freshness of the resulting sound.

As a composer, Tenney rejected the rhetorical quality of 19th century music, finding no point in music’s attempting to convey meaning. “I don’t have something to say unless I’m working with text, where I do have something to say, but that’s in words,” he once explained in an interview.

Instead, his concern was exclusively with the quality of sound and how it is perceived. Even after making extensive studies of the perception of music, he never claimed to understand exactly why music fascinates us. But he felt that if he got rid of everything emotionally extraneous in a composition’s musical content, emotion would inevitably be supplied by the attentive listener.

Ironically, winnowing down music to experiential sound ultimately made him a great eclectic. It was his tendency to come up with subtle means of connecting diverse movements by stripping their styles to the core in search of what they had in common. In a 1984 work for two pianos, “Bridges,” he bridged the gap between the elaborate pitch structures of Partch and the non-pitch structures of Cage, who was happy to use chance procedures to choose his notes. In a work 20 years earlier, when he was a member of the original Philip Glass and Steve Reich ensembles, he wrote a repetitive score using a 12-tone row, which was just the kind of thing Glass and Reich were rebelling against. An early electronic music effort, “Collage #1 (‘Blue Suede’),” was a 1961 deconstruction of Elvis Presley, something shockingly radical at the time.

James Carl Tenney was born Aug. 10, 1934, in Silver City, N.M. His initial interest was in science, and he enrolled in the University of Denver in 1952 to study engineering. But he had learned piano as a boy, and after he heard Cage play his “Sonatas and Interludes” for prepared piano when he was 16, Tenney told The Times in 2002, music “blew me away.”

He was especially impressed by how Cage drastically altered the sound of the piano by inserting screws, bolts and a rubber eraser in the strings. And that was the kind of engineer he quickly realized he wanted to be. After two years in Denver, he transferred to New York’s Juilliard School to study piano with Eduard Steuermann, the pianist who premiered many of Arnold Schoenberg’s scores. A year later, he entered Bennington College, where he received a bachelor of arts degree in 1958. He earned a master’s in music from the University of Illinois, where he studied with the electronic music pioneer Lejaren Hiller and played in Partch’s Gate 5 Ensemble. Upon graduation, Tenney took a job at Bell Laboratories to do research in the new field of computer music.

Still, Tenney was anything but single-minded in his pursuits. Besides developing friendships with Varese and Ruggles in the decade between 1955 and 1965, he collaborated with the experimental filmmaker Stan Brakhage, who had been his friend at Juilliard, and began exploring performance art, which was just taking off, with his first wife, artist Carolee Schneemann. He and Schneemann participated in events with Fluxus artists, and he became a kind of technology guru for the likes of artists Nam June Paik and Yoko Ono.

After leaving Bell Labs in 1964, Tenney took posts at Yale University and Brooklyn Polytechnic Institute in New York. In 1970, though, he made a break with the East Coast and moved to Los Angeles to teach at the newly opened California Institute of the Arts.

That led him to rethink his music and simplify his formal procedures in a series of “postcard” pieces, each written on a 3-by-5 card. After five years at CalArts, he spent one academic year at UC Santa Cruz. In 1976, he accepted a post at York University, Toronto, where he remained until returning to CalArts in 2000.

In Toronto, Tenney became a leading figure on the Canadian music scene. With the greater public support for experimental art in Canada, he began to get orchestral commissions, to make recordings (although never on major labels) and to develop a reputation in Europe.

In his final six years at CalArts, Tenney turned from radical eclecticism to radical synthesis. He returned to his roots, studying and teaching the works of the early American mavericks and playing piano in public. In 2002, he performed for the first time, and to great acclaim, the work that had set him on a path into music half a century earlier: Cage’s “Sonatas and Interludes.”

Tenney published two theoretical books, and his music is recorded on a variety of small independent labels.

Besides his wife, he is survived by sons Nathan and Justin Tenney; daughters Adrian Tenney and Mielle Turner; and grandchildren Sean, Ryan and Chad Turner.

No funeral details were announced, but CalArts is planning a memorial concert in the fall.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.