Wexler Dreams of Well-Rested Film Crews

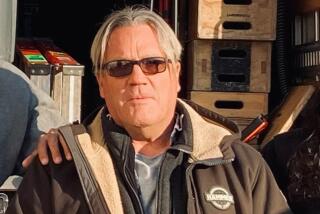

One of Hollywood’s legendary cinematographers, Haskell Wexler wants to awaken the industry to the problem of sleep deprivation plaguing its crews.

Wexler, 84, sports a resume that includes directing the groundbreaking 1969 political drama “Medium Cool” and winning cinematography Oscars for “Bound for Glory” and “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?” Now he has directed “Who Needs Sleep?” a documentary inspired by the death of assistant camera operator Brent Hershman in a 1997 car crash. Hershman was driving home from the set of the movie “Pleasantville.”

Wexler explores the facts about sleep deprivation, even noting the role it played when he rolled his beloved El Camino. Wexler also takes aim at producers and the International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees, which represents film crews, for failing to guarantee that workers are properly rested.

Since “Who Needs Sleep?” premiered in January at the Sundance Film Festival, Wexler has been screening it to gain support for work rules that would give crews more time to rest. Wexler’s film, which lacks a distributor, was recently showcased at an event sponsored by the Writers Guild of America, West, and the Screen Actors Guild.

Last week, he visited The Times to discuss his cause.

*

Question: Throughout your career, you’ve worked on films that address various labor and social issues. What prompted you to do a film on this topic?

Answer: The death of a fellow worker who crashed his car after driving home after a 19-hour day on the set of “Pleasantville.” I knew quite a few people who worked on the film and I admired the fact that they didn’t let it go. They basically said, “This shouldn’t be” -- that his death should not be in vain.

What attracted me to this is that the crew became socially active. They had enough faith in what America is all about to speak up. It was such a dramatic event. I felt I had to dig into this whole issue of sleep and time.

*

Q: From this tragic incident, what broader conclusions did you draw about sleep deprivation in Hollywood and society as a whole?

A: When you bargain with the bottom line such that you abuse your health, neglect your family and you crash your car, it’s tragic.

My film deals a lot with the issues of Hollywood, but I’ve learned sleep deprivation is a nationwide problem. We’re living in a 24/7 culture which robs us of what might be considered normal life. We have to restore some kind of balance between our work lives and our personal lives. All the medical and scientific knowledge is clear that not getting enough sleep is extremely damaging to our health and contributes to a host of various serious diseases, including heart attacks, obesity and depression.

*

Q: In your career, did you have many personal experiences working such hours?

A: Personally, I’ve been very fortunate because I’ve worked with directors who are good directors and who don’t work long hours for various reasons, not just because they’re being nice but because they find it unproductive.

*

Q: Haven’t grueling hours always been part of the filmmaking business?

A: No. When I worked in the 1950s and 1960s, eight to 10 hours was a normal working day. Then in the ‘70s, the normal grew to 12 hours. By the ‘80s many shows were budgeted at 14 hours. Today, we see workdays of 16 to 18 hours.

*

Q: So what’s behind the increase in work hours?

A: I would say one word: stupidity.... The people who make the movie budgets are sitting in some room in Switzerland in front of a computer with numbers, and they say this picture has to cost X. It’s all mechanical and numbers. But you’re dealing with something that’s not on an automobile production line.

*

Q: You also single out your own union and Tom Short, president of the International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees, for some blame.

A: There was a petition [to prevent excessive work hours] with over 10,000 signatures. Then the union took the petitions and put them in a suitcase. It fell into a black hole. Short may be president of the IA, but he uniformly represents the producers. I think he’s there to deliver a compliant workforce.

*

Q: Yet, as you point out, the issue is a complex one.

A: What I’ve learned in making this film is that there is no single villain. We’re all the bad guys because it’s part of our culture toward work. The one thing that incapacitates all of us is fear, fear that this might be your last job and that if you don’t do it, somebody else will.

*

Q: So what can be done to reduce work hours for Hollywood crews?

A: We’re asking workers and producers to not work more than 12 hours on a Friday in June so we can devote a full weekend to our families and friends. This is being organized by a nonprofit organization called 12On/12Off, which is dedicated to promoting saner hours for workers in entertainment.

*

Q: You’re 84. Wouldn’t this project have been more suited to someone half your age with young kids at home?

A: I wanted to ask the question about why we work. That’s a question for all of us to ask. For an older person, of course, it’s more severe because I see the goalposts, so that gives me some energy I might not have had.

*

Q: On average, how much sleep do you get a night?

A: Seven hours. When I’m working, four hours.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.