Harrowing visions of crime and punishment

Park City, Utah — A violent, surreal inquiry into morality, causality and the zero-sum nature of revenge, “Oldboy” tells the story of a man abducted and locked in a hotel room for 15 years by an unknown enemy.

Oh Dae-su (Choi Min-sik), a Seoul businessman on a drunken bender, lands in a police station one night and has to be bailed out by a friend. Back on the street, he mysteriously disappears while his friend’s back is turned. He wakes up in a strange hotel room, where he remains, inexplicably, imprisoned.

Told nothing about why he is being kept there, Oh Dae-su passes the time watching TV, making lists of potential enemies, punching the wall and slowly going mad. Just as unexpectedly released years later, he is given money, a cellphone and five days to figure out who imprisoned him and why.

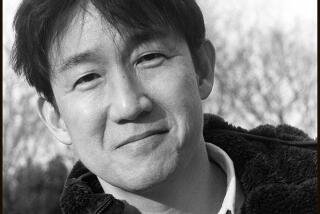

South Korean director Park Chan-wook’s fourth movie, “Oldboy” was one of two of the director’s films screened at Sundance in January. (He also directed one of the three short films that make up the pan-Asian trilogy “Three ... Extremes” which also involves a captor and a captive: A disgruntled actor takes a director and his wife hostage in their own home and slowly tortures her. Lions Gate is releasing the film here in the fall.)

“Oldboy,” which won the Grand Jury Prize at the Cannes International Film Festival in 2004, opens in Los Angeles on Friday. I spoke to Park Chan-wook in Park City through an interpreter.

You were a philosophy major in college and worked as a movie critic before becoming a director. How did these experiences influence your approach to directing?

Actually, I was a director before I became a film critic, but between my first and second movie and my second and third movies there were long gaps. The second movie didn’t make it at the box office or go over well with critics.

But I was married and had a baby, so I needed to make a living. That was the reason I became a film critic. I was very active. I was the most active film critic in Korea. I would show up on TV a lot.

How did your background in philosophy influence your aesthetics as a filmmaker?

I don’t think I was influenced by a particular philosopher or philosophy, but philosophy influenced my attitude. The word “radical” means progressive, but it’s also related to “root.” I try to get to the root of things, to analyze them thoroughly, not superficially.

In both “Oldboy” and “Three ... Extremes,” characters get put in elaborate traps that they must find a way to free themselves from by solving some kind of moral problem.

If I had to choose one phrase common to my films it would be “moral dilemma.” We are destined to make a lot of choices every day in life. And you always have to consider ethical consequences. I find this very hard, so it’s an issue I want to deal with in my films.

Both of the characters in “Oldboy” and “Three ... Extremes” have done something wrong, but it’s so minor they don’t remember what it is. And yet they are punished severely. What are you saying about the impact of their actions?

In “Oldboy,” the victim Oh Dae-su forgot what he did wrong because it was so small. But for Lee Woo-jin [his captor, played by Yu Ji-tae], it was a very big event that changed his life. Very small actions can hurt more than we know. I think the reason human relations are so complicated and tough is because even though we mean well -- I don’t think there are that many evil people in the world -- our small actions can really hurt others.

And yet the sin Dae-su has committed against Woo-jin was not only small, it was indirect.

Oh Dae-su might find it really unfair that he alone is punished, because he wasn’t the only one involved in what happened. But Woo-jin’s objective is not justice. He doesn’t care about whether he’s being fair to Oh Dae-su. He seeks revenge for his own pleasure.

What are you saying about vengeance, then? Why is it such a recurring theme in your films?

Well, I should say that the villain, the actor, in “Three ... Extremes” isn’t out for revenge, exactly. The director character was very nice to him, maybe too nice. The director didn’t take anything from him. He becomes a target because he is a nice person.

But it seems like a sort of karmic revenge.

The villain feels that goodness should belong to the poor, not to the rich. That’s his logic. In old stories, poor people are portrayed as nice, simple, affectionate and compassionate. But in real life, I don’t think that’s the case. The rich have a good education and everything they need. Poverty is hard, and poor people envy what they don’t have. I find that to be a tragic reality.

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.