Team Puts Glitz in Events for Governor

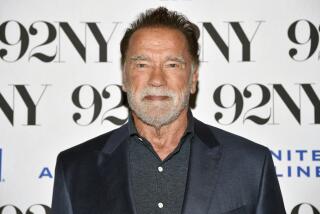

Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger in his first six months has developed a style for his public events that is part rock concert, part car rally, and part reality TV.

When Schwarzenegger moves around the state, he often appears in front of giant backdrops meant to convey his larger-than-life status and an on-the-move image. He shares the stage with roaring trucks, tanks, buses and giant military aircraft, and has driven himself to events in alternative fuel and farming vehicles.

His advance team employs extensive lighting to eliminate shadows and blasts classic rock -- from the Beatles to Elvis -- into makeshift arenas that have been crammed with people. The governor often makes his entrance from the back of the audience and through the crowd, which allows him to interact with people as he takes the stage.

To take a glimpse behind the scenes of a Schwarzenegger appearance is to happen upon a little known cast of gubernatorial aides and event producers who work to create just the right pictures of Schwarzenegger. “They are top shelf,” said Ed Emerson, who did advance work for former Gov. Gray Davis and President Clinton.

Preparations for Schwarzenegger events are led by senior advisor Fred Beteta, a Santa Monica native and longtime advance man who began his career driving in President Reagan’s motorcade. Events are put together by a team of five men and two women, with the assistance of a Bay Area production studio.

But the essential formula for a gubernatorial event is to lean heavily on the stage presence of Schwarzenegger. Events are designed to allow him to ad-lib remarks, fix staging problems on the fly, and improvise gestures he thinks will make good pictures.

“The idea is that we give him a lot of tools to play with, and we do try to anticipate what he might do or might not do,” Beteta said. “But the worst thing you can do with him is to try to script every little thing. When he gets up there, he’s going to do what he feels is right in that moment to create the visual and deliver his message.”

The signing of the workers’ comp bill in Long Beach offers a case in point.

Two weeks beforehand, communications director Rob Stutzman asked Beteta to plan a major event on workers’ compensation. With negotiations on a bill to reform workers’ comp then incomplete, it wasn’t clear whether the Schwarzenegger appearance would be to sign a bill or launch a campaign for a workers’ comp initiative on the November ballot.

Beteta dispatched Eddie Kouyoumdjian from the advance team to scout locations. Kouyoumdjian visited eight spots across the Los Angeles area, the state’s largest TV market. Each was a factory with large numbers of employees; he checked out a car plant, a vitamin manufacturer, a cannery.

But the Boeing plant in Long Beach was particularly attractive. It makes the giant U.S. Air Force C-17 transport plane, the sort of larger-than-life backdrop the governor prefers. What’s more, Boeing executives had testified publicly on the need for workers’ comp reform.

On a Monday afternoon, a week before the event, Beteta and his team left a Schwarzenegger appearance at a Costco in Burbank and drove to Long Beach to scope out Boeing. Joining Beteta and his team was George Parrish, the technical director from Hartmann Studios. Founded two decades ago by a creative director at Macy’s, Hartmann stages events of all kinds, providing sound, lighting, stages, greenery and props. Most of its clients are corporations, but the company has also staged speeches for President Bush and the Dalai Lama.

Specialized Roles

During the recall campaign, Matt Guelfi, a Hartmann vice president, began working with Schwarzenegger to produce rallies. Hartmann also handled the inauguration and more than 40 gubernatorial events; Guelfi sometimes stands in for Schwarzenegger during run-throughs because he and the governor are the same height. Parrish supervises the Hartmann crews who bring the stage and sound system by trucks, helps choose the music for events, and -- in his trademark business attire of leather jacket and jeans -- sits in on meetings of the suit-wearing advance team.

(Production costs are paid with campaign funds, according to the governor’s office).

On their site visit to Boeing, the advance team and Hartmann representatives looked at planes in different stages of the production process that they might use -- before settling on a fully built but not yet painted plane in the center of a huge hangar. Two advance team members rode an electronic lift into the hangar’s rafters. One looked for places where photographers might take pictures. The other took photos that would be turned into schematic drawings detailing how the stage would be set up.

The staging plan comes from Beteta. He wants to use the plane as a dramatic backdrop, but insists there should be many employees in the background. After all, the message is that workers’ comp reform could save people’s jobs, not airplanes, he says.

He asks Boeing officials if scaffolding around the plane can be removed to give cameras a cleaner view of the plane (it can). He wonders if employees can be placed on the wings of the plane (They can, but they’ll have to wear harnesses). He asks if the plane, which is carefully lined up on the hangar, can be turned to the side so it faces TV cameras at an angle. The plane is so large that viewed head on by cameras, the tail would not be visible and it might not be clear to viewers what the plane is.

“It works,” Beteta says as the advance team departs after three hours at Boeing. “It’s active. It’s playful. It’s larger than life.”

By Friday, 72 hours before the event, a workers’ comp deal is done. And much of the team has returned to Boeing to plan a bill signing.

Saturday is spent arranging three stands of bleachers to create the feeling of a small crowded stadium inside the cavernous hangar. Boeing workers spend hours on Saturday turning the C-17 rightward a few feet at a time to create the angular backdrop that will look best on camera.

By 8 a.m. Sunday, Beteta and the team are back at Boeing. In the late afternoon, a dozen staffers from other parts of the governor’s office -- cabinet, legislative, press -- arrive for a “countdown” meeting during which staff assignments are handed out and Schwarzenegger’s time is detailed down to the second.

The Sunday meeting ends around 7 p.m., but the advance team sticks around, tinkering. Parrish works on making the sound loud enough to overcome the buzz of the hangar’s fluorescent lights. Beteta checks out camera angles from the media riser. He moves a few feet at a time, cupping his right hand as if it was a circular camera lens and peering at the stage through it.

It’s 10 p.m. by the time the advance team and Beteta call it a night. They are back the next morning for more tweaking and to give the event a soundtrack. Parrish and Beteta are hunched over a laptop, looking at rock songs that have been downloaded in order to put together a playlist that will liven up the crowd during Schwarzenegger’s entrance and exit. (“Born in the USA” is ruled out immediately).

The musical question becomes: What should they play for the governor’s entrance? Beteta suggests Tom Petty’s “Running Down a Dream” and begins to sing it. Parrish counters with Pat Benatar’s “Hit Me With Your Best Shot.”

Stutzman, the communications director, arrives and suggests Van Halen’s “Right Now.” Beteta replies that the song loses its fire too quickly, and Schwarzenegger has a long walk to reach the stage.

Ultimately, they decide to use Bachman-Turner Overdrive’s “Taking Care of Business” -- a staple of gubernatorial appearances -- for the exit. For the entrance, they consider a dance remix of the Elvis song, “A Little Less Conversation,” with its Schwarzenegger-friendly second line, “a little more action please.”

“Sideburns, it is,” Stutzman says.

Schwarzenegger arrives shortly after 1 p.m., taking up residence in a Boeing conference room. He spends 15 minutes inside the conference room, going over a schematic drawing of the event stage. The governor studies the drawing, then asks questions. What is the picture Beteta has in mind for the moment when Schwarzenegger is seated? How will the legislators he introduces enter the stage?

As the time nears 2 p.m., Schwarzenegger is brought by golf cart to a point behind the bleachers.

Event Underway

The Elvis song begins to play at rock-concert-high amplification and Schwarzenegger walks into the back of the crowd, leaving Beteta behind. The usually composed Beteta throws a fist in the air and shakes his hips, doing the twist. It is a release after two weeks of preparation. Schwarzenegger begins his speech by acknowledging the setting. “It’s a plant of action, that’s why we wanted to come here,” says the governor. “Big action here,” he adds, glancing back at the plane. Called to the stage by the governor, Assembly Speaker Fabian Nunez, a Los Angeles Democrat, seems a bit overwhelmed.

“I feel like I’m in a Hollywood production studio,” he says.

Just before the bill is signed, Schwarzenegger invites a state senator to the stage to join the tableau. But the senator heads for a spot on the wrong level of the four-tiered stage. If the senator takes the wrong mark, he may throw off the symmetry of the images that will be broadcast around the world.

The governor recognizes the mistake immediately. He grabs the off-course lawmaker by his right hand -- and, with a grin to make the maneuver look like a handshake -- yanks him up a stage level to his proper mark.

“He is engaged with every aspect of this,” Beteta says. “He truly understands the importance of the visual.”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.