They’re Sticking It to Us With Antique Vaccines

The flu vaccine debacle has been a long time coming. The United States has two main suppliers of the vaccine -- one in France, one in Britain. The latter has changed hands about six times in the last several years, and its current owner, Chiron, apparently inherited a mess in the production plants. Stray bacteria contaminated some batches, and all of Chiron’s vaccine supplies -- enough for half the United States -- had to be thrown out. Panic has ensued. Doctors and public health officials across the country have rationed flu shots, faced long lines, held lotteries, even dealt with death threats.

Because flu shots save lives, it is surprising that the vaccine supply is so fragile. A superannuated technology, combined with the Food and Drug Administration’s entrenched conservatism and reluctance to accelerate the development of new production methods, has annually forced flu vaccine experts to rely on imperfect technology to create imperfect vaccines, risking contamination and shortage.

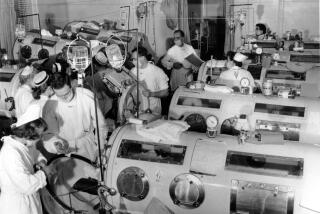

The vaccine production technology dates to the 1930s, when scientists discovered that influenza virus can be grown by inserting it between the membranes of fertilized eggs and then keeping the eggs warm. The top of the egg is sawed open, the virus inserted and the egg sealed to allow the infected chicken embryo to grow. Then the egg matter and embryo must be separated out and the virus purified. Any slip-up along the way can introduce bacteria.

The original flu vaccine virus is 70 years old. “It’s a very odd virus,” said Jeffery Taubenberger of the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology. “It’s been passaged, cultured, hit over the head ... so it will grow in mice, grow in eggs, grow in ferrets.”

But this strain alone won’t protect anyone from anything. To do that, the virus has to be mixed with the strain scientists think -- eight months in advance -- will be circulating next winter. The new strains provide the surface proteins, or antigens, that produce immunity. Every year it’s a gamble. In 2003, scientists picked the wrong strain.

“When people identify a new mutant strain that has changed enough so that existing immunity won’t block it, they decide this is the basis for this year’s vaccine,” Taubenberger said. “So they [mix] it

Even when the match between vaccine and virus is close, flu vaccine is only partly effective. Vaccinated people are 70% less likely to get the flu, while for the very old, vaccines are even less protective. If flu experts misjudge, they can’t shift gears to develop something else.

This is where new technologies come in. Cell culture technology, which allows a huge supply of virus to be grown rapidly under sterile conditions, would give vaccine developers greater flexibility. Recombinant DNA technology could produce appropriate vaccines in even less time. “With molecular biology, not only can you grow vaccine strains in huge quantities, you could very quickly make a recombinant vaccine strain using the old internal genes from the [original] virus and a sequence that could come right out of a person,” Taubenberger said.

This technology would also be much safer. Because virus samples are taken from sick people’s throats, there’s a risk of HIV or prior disease contamination. With recombinant DNA technology, only the virus’ genetic sequence is used, so no other infectious agents can come along for the ride.

Because of the FDA’s reluctance to fast-track new technologies, some blame the agency for the flu vaccine shortage. Peter Palese, a leading flu researcher at Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York, doesn’t accuse the FDA of “malicious intent.” Still, he said, “it comes down to the wrong decision, to being Luddites, being anti-progress, being anti-technology. Their first rule is ‘To do no harm’ -- but they are causing harm.”

Jesse Goodman, director for the Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research of the FDA, insists that the agency embraces new technologies, pointing out that a number of current vaccines -- inactivated polio, hepatitis A and chicken pox, among others -- are grown in cell cultures. “If scientists can ‘qualify’ a cell line -- show that it isn’t contaminated -- we would definitely encourage that,” he said. The FDA, he adds, “doesn’t see any particular safety issues” with recombinant vaccines, though “the protein being expressed may not elicit as strong an immune response” as viral antigens grown in a living cell.

But Palese cites the example of a vaccine developed against cervical cancer to illustrate the FDA’s basic conservatism. Almost all cases of cervical cancer are caused by human papilloma virus (HPV). The agency insists on using a pathology marker that looks for cancer cells in patients over a 10-year period to test the new vaccine’s efficacy. But many women never develop cancer cells, and 10 years is a long time to run a clinical trial. While these trials progress, how many women outside the trials will die of cervical cancer?

A better way, Palese says, is to look for the virus in vaccinated women -- if there is no live virus, there will never be cancer. And that should be enough to prove to the FDA that the vaccine works. “This is a prime example of how [the agency’s] conservative thinking and attitudes are hindering the development of new treatments,” he said.

With respect to flu, Palese said we have the technology to “develop vaccines that would be good for five years. But since the FDA is so recalcitrant, no company will ever develop that, unless the FDA embraces more modern approaches.”

But looking for change at the FDA, particularly in vaccine development, is like watching a glacier melt. Unlike new drugs, new vaccines are never put on a fast track. As a recent article in the New England Journal of Medicine pointed out, the stringent requirements -- the constant need for licensing and relicensing of vaccine production when a company moves its facilities; the emphasis on developing full-production capacity before the FDA is willing to certify the vaccine -- and low profitability make many companies resistant to producing existing vaccines, much less develop new technologies. Some companies have gone out of business because they were forced to sell their products at fixed prices while their costs to comply with FDA regulations were rising.

The money is in new drugs, not in new vaccines, and FDA regulations seem to be looser for treatments than for prevention.

This is a shame. The simplest and best way to handle many diseases is to treat people with safe, effective, long-lasting vaccines -- before they ever get sick.

And the best way to make flu vaccines for the 21st century will not be found in technologies dating from the 1930s.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.