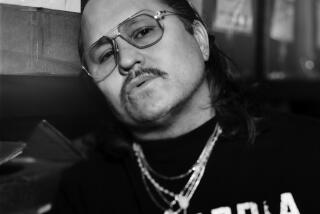

Is There Substance Behind Clothing Factory Owner’s Brash Style?

In Los Angeles, where garment factory owners seem most likely to make the news when they are raided by the government, Dov Charney wants to be famous, not infamous.

The 33-year-old owner of one of the city’s largest garment factories has built a reputation as a fighter for workers’ dignity. Media profiles praise him for lavishing generous pay and benefits on his employees and preserving jobs that might otherwise be lost to foreign sweatshops.

Charney takes out full-page newspaper ads accusing his competitors of exploitation, hires buses to drive his workers to immigrant rights rallies, and invites labor organizers into his factory.

In fact, Charney started offering health insurance to his 1,000 employees only two months ago, and he does not provide paid sick days, paid vacation or retirement benefits. But because he pays an average of about $10 an hour -- much more than the state’s $6.75-an-hour minimum wage -- and helps employees take advantage of public benefits programs, he has successfully sold himself as a champion of better working conditions in a county with 90,000 apparel workers.

“In a situation where everybody’s scrambling for bits and pieces at the bottom, a guy who is halfway decent stands out as a saint,” said Richard Appelbaum, a UC Santa Barbara sociologist who co-wrote a book on the Los Angeles garment industry of the 1990s.

A PBS television documentary last year featured Charney leading a tour of his downtown factory -- American Apparel -- comparing himself to Christopher Columbus because his is “the first company in the state committed to removing exploitation” from garment making. And Time magazine suggested that the U.S. garment industry “could use more companies like Charney’s.”

Apparel employment is up about 25% in Los Angeles County since 1980, despite job losses in recent years. Sewing has become the largest sector of the county’s manufacturing economy, surpassing much higher-paying industries such as aerospace.

But only about a third of Los Angeles garment factories comply with federal and state labor laws, such as minimum-wage standards and overtime pay and record-keeping requirements, according to U.S. Labor Department studies.

Into this economy came Charney. Born in Montreal to a Harvard-trained architect and a painter and art professor, he has always relished playing the rebel. At age 11, he published a neighborhood newspaper that ran another child’s firsthand account of being molested.

As a student at Choate Rosemary Hall, the same Connecticut boarding school attended by President Kennedy, Charney went into business.

He stocked up on blank T-shirts at Kmart (cheaper and better than Canadian shirts, he said) and hauled them back to Montreal on weekend train trips. There, a friend silk-screened designs on them for sale on the streets.

At Tufts University near Boston, Charney was selling T-shirts wholesale out of his dorm room. In his junior year, he dropped out to sell shirts full time in South Carolina. He set up shop in Los Angeles in 1997, consolidating his operations.

Along with T-shirts, American Apparel sells a few styles of bras, panties, knit tops, shorts and pants. Charney said the firm is profitable; it had $22 million in sales last year. This year, he said, he has nearly doubled his work force, 700 of whom operate sewing machines.

Charney said he is able to pay a relatively high wage for several reasons. His shirts are a premium product, sold at about twice the price of other T-shirts. Unlike most garment companies, American Apparel designs, markets and sews its products in-house.

By cutting out contractors and middlemen, Charney said, he saves money he can pass on to workers, and he can better control working conditions.

Charney himself photographs his garments on models he sometimes recruits on the street or at strip clubs, and writes copy for the company’s ads and catalogs. Although he estimates that he spends about 50 hours a week at the factory, Charney said he is always either working or thinking about work. After all, he explained, “T-shirts are everywhere.”

He says he lives a modest life in a two-bedroom house in Echo Park, and he comes to work dressed in his own T-shirts. “I believe in functionality,” he said.

Two years ago, Charney and his business partner -- Sam Lim, an established L.A. garment contractor -- moved their operation to a 165,000-square-foot plant in a former Southern Pacific rail depot at 7th and Alameda streets.

There, workers paid by how much they produce -- with a $7-an-hour minimum -- focus intently at their sewing machines, sitting in chairs that look as if they were salvaged from restaurants and offices. Some wear a strip of fabric across their noses to keep from inhaling the airborne particles generated by the cutting and sewing.

The machines are noisy, but no one wears earplugs. Fans stir a breeze in the afternoon heat. (A promotional video on the company Web site touts “heating and ventilation” as some of American Apparel’s sweatshop-free attributes.)

Charney and his workers, most of whom are Latino immigrants, proudly point out the telephones and drinking water dispensers near the restrooms. Massages are also available.

In emergencies, when workers sometimes take collections for colleagues, Charney adds “a few hundred dollars.” He also recently gave $500 to a church building project in an employee’s hometown in Guatemala.

But Charney said he would rather avoid such “little charitable events” and focus on improving wages and benefits permanently.

Until recent production efficiencies boosted the average machine operator’s pay to $10 an hour, Charney estimated their wages at just under $9 an hour. That is less than the city’s official “living wage” of $9.52 an hour, which firms with city contracts are required to pay workers who get no health benefits.

Labor organizers and garment industry representatives say Charney’s pay scale is at the high end of the industry.

“If he’s complying with the law, I applaud him for that. He’s in the upper percentile, but ... there are a number of people who do that,” said Joseph Rodriguez, executive director of the Garment Contractors Assn. of Southern California. The group represents about 200 firms generally considered the more reputable companies in the industry.

American Apparel has not been cited for any labor or safety law violations, said Dean Fryer, a spokesman for the California Department of Industrial Relations.

Kimi Lee, executive director of the Garment Worker Center, a workers rights group in the Garment District, said Charney’s willingness to speak out against worker abuse is unique among the industry’s employers.

By aggressively publicizing his company, Lee said, Charney is serving “as a good example for others, that you can do things right and still make a profit.” She also praised him for hiring workers who have been blacklisted at other firms for pursuing wage claims or protesting working conditions.

Charney’s ads say his workers have health insurance. But until two months ago, any such coverage was not provided by the company. American Apparel takes credit for encouraging its employees to enroll in government programs such as Healthy Families, which finances health care for low-income children.

A mobile nursing van that visited the company weekly was provided by a nonprofit group, but it stopped coming when the group lost a grant. Workplace English classes are paid for and managed by the Los Angeles Unified School District.

Walking through his factory, Charney says American Apparel and its customers are a repudiation of business based on exploitation.

Then he pulls a booklet of writings by Mao Tse-tung from his back pocket, brandishing it for a moment in front of a visitor and tossing it onto his desk.

Charney says his pay and benefits should be better, and vows to improve them. Pay is “20% below the level I find acceptable, and that’s bothering me,” he said.

He hopes to avoid unionization, which Charney worries could cost him his independence. But he vowed to follow his workers’ wishes on the subject. “I would never, ever commit the sin of opposing [an organizing effort] or counseling them against it,” he said.

Charney gave two summer interns from the Union of Needletrades, Industrial and Textile Employees permission to roam the factory whenever they pleased and allowed them to conduct a survey of workers.

He said his new production system has boosted output, enabling him to pay more.

Garment factories typically assign workers to a single specialized task, such as attaching sleeves or collars, for which they are paid by the piece. Charney’s new system groups workers into teams, with a team’s pay based on the number of garments completed by the group.

“In Morocco, there are teams doing 275 dozen shirts a day,” he said. “At my pay rate, that’s $20 an hour” per person. “We can go way up.”

Carlos Dominguez, American Apparel’s sewing manager, said members of one team at the plant are already earning $18 an hour.

Araceli Castro, a quality inspector at the company, said her $7-an-hour job is the best she’s had since arriving in this country 20 years ago.

“It’s clean,” she said of American Apparel. “There’s lots of room and good ventilation. Sometimes I feel like I’m dreaming and I don’t want to wake up.”

Castro, 42, said she once worked in an El Monte garment factory where Thai workers were found toiling in slave-like conditions in 1995, and at another factory owned by the same company in downtown Los Angeles. At those factories and others, Castro said, she sometimes earned as little as $2 an hour, working 12-hour days, seven days a week.

Castro has joined lawsuits against retailers alleging unfair labor practices by contractors that supply the stores, including garment factories in which she worked.

Because of that activity, she said, she has been blacklisted in the industry.

“I’m grateful to Dov for hiring me,” Castro said. “He knows I cannot get a job in other factories.”

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.