A whirl of me firsts, It Girls

This morning in New York, Fashion Week revs up.

The only difference between the fashion shows and the toy fair or a consumer electronics convention or any trade show that brings hordes of buyers and sellers to New York twice a year is that fashion is supposed to be glamorous. When fashion people (and never, never call them garmentos or say they’re “in apparel”) converge on a white tent the size of a football field in Manhattan’s Bryant Park to peruse the 2003 fall collections, the espresso machines go berserk. This is good. This signals excitement and business, and right now business in New York’s top two indigenous industries -- fashion and finance -- is one stuck zipper.

So this week is important to gin up excitement over a change in hemlines or a new teenage model just in from the Czech Republic and maybe jump-start that business. This can happen when impossibly chic fashion people flock, about 1,000 at a time on the hour, to 16-minute glimpses of leggy models trained to walk like camels on a runway. If all goes well, an editor at Vogue might be overhead after a show cooing “Gale force!” or “Genius!” The outfits seen on the runway may never be sold in stores, but they’ll definitely appear in fashion magazines and videos, and then we’re all supposed to “get inspired” to go shopping for some lesser version of this season’s cargo miniskirt or peasant blouse or Balenciaga bag at our local Nordstrom. That’s the system.

There will be about 100 shows this week in New York. Carolina Herrera’s is the first big one under the tent today, and Calvin Klein’s Friday night event in a studio on West 15th Street is the last. Then the whole fashion clan, after infusing about $50 million into the New York economy, packs up its Louis Vuitton luggage and heads for more shows in London, then Milan and onto Paris. After 31 days of clothes, clothes, clothes, and coffee, coffee, coffee, the editors, buyers, photographers, makeup artists, hairdressers and assorted hangers on go back to where they came from. (Only the designers head for their vacation villas on exclusive islands.)

A year ago at this time, New York had been chastened by terrorism and fashion had pulled in its plumes. The shows were downsized, parties were soberish and the fashionistas behaved a teensy weensy bit more professional. Instead of slavish attention to celebrity, they focused on the clothes.

New York has since reclaimed its primacy in all things, and again it’s a week for fashion’s Emperors to strut about in their New Clothes. Which means, despite an ailing fashion industry (retail spending is down 6%,) design houses are staging extravaganzas again, spending $350,000 to $2 million per show. Fashion editors are cozying up to celebrities and socialites with renewed vigor. And the industry as a whole is saturating our lives with brand names (think sunglasses, sheets, perfume) instead of stirring our emotions over new designs. The shuttle, the war, unemployment, potential terrorism -- none of it matters this week. Instead, thousands of fashion people will be elbowing their way past each other to gossip, party, preen and most of all keep a firm grip on that glamorous patina of a $14-billion business that is so vital to New York.

But the week preceding the shows was anything but glamorous. Perhaps it’s petty, even boorish, to focus on the beast that drives all those 16-minute spectacles on the runway, but as every woman knows, glamour does not come effortlessly. It’s like watching the run-up to a Broadway opening, when people are smudged with greasepaint and actors are getting sewn into their costumes just before the curtain’s up. It’s not pretty. Last week, designers in their studios were madly winnowing their collections from 100 outfits to 45. Buyers were finalizing budgets and fashion editors, a breed of taut 40-somethings who have no interest in anybody but themselves, were getting their highlights done.

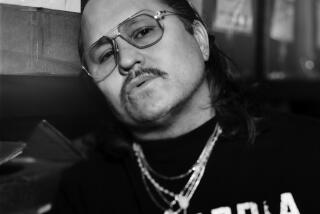

Probably the worst job in the Garment District, however, was left to young assistants who do the seating for shows. Typically, 2,500 invitations are issued for 901 seats under the big tent. Always at the last minute the assistants hear from assistants of ditzy actresses or East Side heiresses who demand front-row treatment. Amid this dismembered universe, in a gray office in Lower Manhattan, James Scully, a Brahmin of the fashion caste, pondered three piles of Polaroids. His knee was bouncing nervously. It was midweek, and Scully had met, briefly, 100 new “girls” and had yet to see one he’d consider extraordinary.

“Nobody, nobody,” says Scully, 37. His job is to cast about 15 models each for the shows of Carolina Herrera, Anne Klein and a new designer, Behnaz Sarafpour. Each season Scully likes to place two or three fresh new faces. “I want to fall in love today, get that crush I get so rarely,” he says. This has only happened a few times in his career during “go sees,” first sessions with new models. He discovered top models Liya Kebede and Caroline Ribeiro and last season’s hot new face, Linda V.

But who will she be this season? What teenager from Canada or Brazil or the Czech Republic who has barely heard of communism but can shimmy into a pair of “Miss 60” jeans like an acrobat, will James Scully make famous this season? Green-eyed, precise and so high-energy he vibrates, Scully is a savant of beauty. Editors, agents and designers rely on his trained eye, his photographic memory and knowledge of fashion history to help them find new models and then nurture their careers. Only Scully can assess a lip-line or a cheekbone and the walk of a 16-year-old girl from Hungary and imagine her as fashion’s next It Girl.

Kate Betts, the former editor of Harper’s Bazaar, wanted Scully by her side soon after she took over that magazine. “Rather than say, ‘Oh, she’s pretty’ or ‘Oh, she could be the next Giselle,’ James can see a girl and figure out what look she can best deliver for a designer or magazine.” Scully, one of 10 children in an Irish Catholic family, left New Jersey at age 17 and came across the river to become an actor. But after working as a sales clerk at Baltman’s, he ascended fast in fashion -- first as a buyer for the Charivari stores, later producing fashion shows for Kevin Krier & Associates, and then in his dream job as an editor for Betts.

But he got fed up with the “In-Stylization” of fashion and with chasing celebrities, and retired with his partner, a top Gucci executive, to a farm in Pennsylvania. Now Scully returns only to make money -- and with the hopes that he’ll fall in love, find that crush.

“Iwould use her this week if she can pull it together,” he tells an agent over the phone as he examines a Polaroid of Le Mather. “She’s got the Break Girl thing.” Mather, 21, is three days into her first visit here from Chicago. Despite a big pouf of dyed blond hair and timid personality, she catches Scully’s eye. It’s her clean American looks. Scully tells her agent to have a “talk” with Mather, to suggest she show some exuberance. But she’s too shy and the hair is a deal-breaker. Designers don’t want her for the shows. Still, Scully expects her back next season. “You wouldn’t believe what six months can do to improve a model’s looks.” After two minutes with a girl, watching her walk and examining her while he takes six Polaroids, Scully can tell if she’ll make it. It seems cruel these brief size-ups. But he is always polite. “Good luck,” he tells each girl and sounds sincere even if he is about to stuff her Polaroid in the wastebasket under his desk.

He’ll spend this week guiding the models through makeup, fittings, right to the door of the runway and then go to Europe to do the same for Gucci and Yves St. Laurent. “Everyone’s waiting for something in fashion to turn around.”

He’s right. The economy is squeezing the beast at the same time it has become bored with itself, tired of copying old looks. Fashion has brought back the ‘50, ‘60s, and ‘70s. The ‘80s have been revived twice in three years. But maybe this week a new girl in a fabulous new design will ooze onto the runway to a bass beat and ignite something authentic, something really glamorous. Whatever that is.