5 Die in Nebraska Bank Holdup

NORFOLK, Neb. — This farm community of 24,000, set amid cornfields and cattle ranges, is a big city by Nebraska standards. Yet not big enough to absorb the horror of a botched robbery Thursday morning that left five people dead in a bloodstained bank.

It was the nation’s deadliest bank heist in more than a decade, and though it left residents shaken, experts said the tragedy is yet another indication of crime’s growing reach into rural America.

Police Chief Bill Mizner choked up as he read aloud the names of the victims--four bank employees and a customer--killed as three robbers shot their way out of the U.S. Bank branch near one of the town’s busiest intersections.

“Evone Tuttle, 37, of Stanton,” Mizner read. “Lola Elwood, 43. Jo A. Mausbach of Humphrey. Lisa J. Bryant.”

The chief paused for a long awkward moment.

“Lisa J. Bryant, 29, of Norfolk,” he continued with difficulty. “Samuel C. Sun, 50.”

He seemed shaken by his own emotion. “Sorry about that,” he said.

On a day of leaden skies, when heavy clouds pressed hard against a desolate horizon, Norfolk residents expressed sorrow, rage, fear and, above all, a sense of betrayal.

“I’m angry. I’m just angry. I know this stuff happens all over the world, but it doesn’t happen in Norfolk, Neb.,” said Dan Kuester, 45, who grew up in a farm town near here and returned to raise his children in the peace of rural life after two decades of globe-trotting with the Army.

“I guess we’re naive about these things,” said his wife, Carla. “I feel stupid for feeling that it couldn’t happen out here.”

The three men suspected in the robbery were captured several hours after the holdup at a McDon-ald’s about 75 miles northwest of Norfolk.

Authorities said the suspects left the bank on foot, stole a white Subaru Outback from a nearby residence, drove it into the countryside then ditched it in a pond. They allegedly then stole a pickup truck to continue their getaway.

Just hours after the suspects were taken into custody, Madison County prosecutor Joe Smith said he would file five first-degree murder charges against each of the men. “Everyone is absolutely committed that the people [killed] here will get justice.”

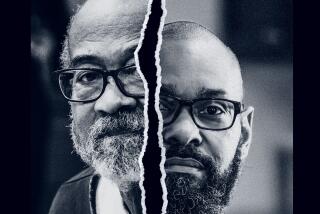

He identified the suspects as Jose Sandoval, Jorge Galindo and Erick Fernando Vela. But he could offer few other details--not their ages, their hometowns or any information about weapons they might have been carrying. And late Thursday night authorities said they were searching for a fourth man in the case.

The fourth man was identified by the Nebraska State Patrol as Gabriel Rodriguez, 26. The agency’s statement didn’t say what role he is believed to have played in the robbery, and calls to the patrol for elaboration weren’t returned Thursday night.

Facts about the robbery itself were slow to emerge. One witness said the men were wearing stocking caps. Another witness screamed in horror as a stray bullet pierced the drive-through window of a nearby Burger King. And a local radio station reported that bank employees might have triggered a silent alarm that sealed the doors shut, forcing the robbers to shoot their way out.

But authorities would confirm none of those rumors. They would not even comment on whether the gunmen escaped with any money.

As dozens of federal, state and local investigators swarmed the stucco-and-glass bank, officials would say only that they needed to review the bank’s security camera tapes and interview survivors--including two employees and a customer who was wounded in the shoulder--before they could reconstruct the tragedy.

For local residents, it was enough just to know that their quiet town had been violated.

“We’ll probably be locking our doors more after this,” one lifelong resident said.

But the bloody robbery here did not surprise criminologists.

“Small towns are seen as easy marks,” said Ralph Weisheit, a professor of criminal justice at Illinois State University who specializes in rural violence.

Indeed, cash-strapped towns across the heartland have been paring down or even eliminating local police departments, relying instead on distant sheriff’s deputies to provide protection. Though Norfolk has its own Police Department, some smaller towns have pooled their resources to hire a single part-time officer, Weisheit said--”so he’ll work in this town on Tuesday and that one on Wednesday and another one on Thursday.”

The result: Nearly 1 in 3 bank robberies unfolded in a small town last year. In the mid-1990s, fewer than 1 in 5 robberies occurred in rural areas.

Tiny towns of just 400 or 500 residents have been hit repeatedly as robbers learn which banks have security guards and cameras, and which don’t.

Slightly bigger, but still isolated, communities such as Norfolk are increasingly at risk as well. In fact, FBI statistics show that on a per-capita basis, towns with populations between 10,000 and 25,000 are now the most likely to experience a bank robbery.

Many small towns also are reporting a surge in other types of crimes, especially burglaries. A tavern in tiny Sterling, Neb., population 507, lost its theft insurance coverage after it was hit twice in the span of a year and a half.

Nearby towns have reported break-ins at Main Street lumber yards and grocery stores, and at schools and cafes. The take may be small by big-city standards--a big-screen TV, perhaps, or a few hundred dollars--but to locals accustomed to leaving their keys in their cars, any crime is unsettling.

“Clearly, crime has become an issue to them when it wasn’t an issue before,” Allen Curtis, director of the Nebraska Crime Commission, said recently.

Dan Bodony, the bank robbery coordinator at the FBI’s Los Angeles office, said rural banks are aware that robbers consider them “softer targets” than urban banks; in recent years, many have taken steps to improve security.

After a spate of robberies outside Lincoln, Neb., several years ago, for instance, several banks closed their lobbies and conducted transactions only through the bulletproof glass of their drive-through teller windows.

“They are being very proactive when it comes to their security,” Bodony said.

Many banks are also sending their employees to workshops on how to handle an attempted robbery. The Workplace Trauma Center, based in Maryland, teaches tellers how to breathe to slow their heart rate and avoid panicking. It has them repeatedly practice opening safes while a trainer holds a fake gun to their head.

Such courses always emphasize that most robbers do not want to harm anyone. Their aim is usually to take the money and run.

But that truism has been shaken in recent years as bank robberies nationwide have turned more violent, and as small-town crime has been increasingly fueled by the drug methamphetamine.

Known as “poor man’s cocaine,” methamphetamine has swept the heartland in the last several years. Addicts can brew it themselves in remote fields and ramshackle trailers, in motel rooms and pickup trucks. And when they’re high, they are often besieged by paranoid hallucinations that can twist them into brutality.

Methamphetamine is considered such an urgent problem here that 12 Midwest governors met last week in Iowa to swap horror stories about the drug and to share law enforcement tips.

There is no indication yet that methamphetamine had anything to do with Thursday’s tragedy. But several analysts said the possibility came to mind as soon as they heard of the bloodbath in Norfolk.

“Drugs are a big driver behind this type of crime,” said George Beattie, executive vice president of the Nebraska Bankers Assn.

As investigators work to unravel what happened at U.S. Bank on Thursday, Norfolk residents are mourning the five victims--and their sense of lost security.

“There’s a big difference between just robbing the bank and doing what they did,” said Lester Felger, 45, a former manager of the U.S. Bank branch that was involved in the holdup.

On most days, the town police blotter registers nothing more serious than a stolen car stereo, a vandalized truck or a suspected shoplifting of $13.96 worth of merchandise from the HyVee market. Now there will be five funerals to attend, five shattered families to console.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.