Greatest Risk of Smallpox Is Fear

Back in 1797, when Edward Jenner first injected cowpox into a human, he surely never dreamt his work would lead to a vaccination controversy more than 200 years later.

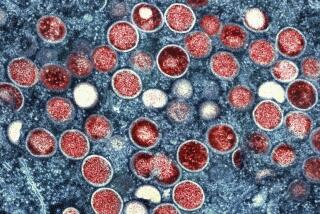

Yet we are now faced with a medical dilemma: With two vaccines made from inactivated smallpox-related virus on the horizon -- one of which is now undergoing clinical trials at the National Institutes of Health -- should we use the outdated and more dangerous live-virus vaccine in the meantime? And if so, who should receive it?

The risk of smallpox appearing in the United States is still theoretical. But ever since Ken Alibek, the former deputy director of Biopreparat, the Soviet biological weapons apparatus, freely admitted to extensive amounts of smallpox existing in the Soviet Union, there is every reason to believe that some of the stockpiled virus may have found its way into the hands of rogue dictators or terrorists. And smallpox may be aerosolized -- if it is sprayed, it could infect hundreds of victims right off the bat.

Still, U.S. public health measures can be relied upon to contain any smallpox outbreak that occurs. All contacts will need to be inoculated, and afflicted patients will be isolated.

Smallpox spreads only when a person is already sick with a fever or rash, so in fact it is harder to spread than more innocent-seeming killers like the flu or measles.

Further, there is reason to believe that everyone vaccinated before 1972 still has some immunity and wouldn’t get as sick from smallpox. This “herd immunity” would also slow the spread in the event of an attack.

The fear associated with smallpox is much more contagious than the disease. Smallpox is one of our ancient scourges, and it captures the dark side of our imaginations. Schoolchildren learn of smallpox as the first bioweapon, distributed in blankets to Native American tribes by British troops during the French and Indian wars of the 1750s. Vague memories of our earliest immunizations against smallpox haunt many of us.

Yet smallpox never wiped out large populations the way influenza and polio did. The greatest risk was always from secondary spread, which existing public health measures may contain. The vaccination program of the 1960s was undertaken largely to eradicate the disease worldwide and not because there was a looming risk to a particular group.

Admittedly, as the risk of war -- and its associated risk of bioweaponry -- increases, it is becoming more reasonable to vaccinate health-care workers and emergency responders. Yet for the protection of the public at large, the push must be to complete the research underway on a safer vaccine.

The old vaccine causes more than 1,000 serious complications per million vaccinated, including brain swelling and unintended viral contagion. This antiquated vaccine is not safe when given to people who have certain skin conditions, are immuno-compromised or pregnant. Unfortunately, these conditions may be hidden. The one recent death from the smallpox vaccine occurred in a military recruit who unknowingly was HIV-positive.

Vaccination may be useful to treat fear, but not when there are such side affects. It is reasonable to accumulate ready supplies of this older vaccine in case an attack of smallpox occurs, but it is not reasonable to use these supplies on the public now.

A recent study in the New England Journal of Medicine shows effectiveness of the old vaccine at 1/10 dilution, a dose that also may dilute the risk. But diluting this dinosaur is not enough. Instead, we must treat our fear with plenty of reason and restraint. Our scientists must be allowed to complete their work on a more modern, safer vaccine, the likes of which are already used for polio, flu, measles and chickenpox.

In a worst-case scenario, public health experts will still have plenty of time to react to smallpox if this old enemy is deployed in an attack against us.