Inevitably, a Non-Reporter News Anchor

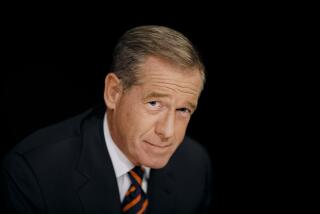

Broadcast journalism crossed a qualitative Rubicon this week, when NBC announced that Brian Williams, a 43-year-old cable-news reader, will replace Tom Brokaw, 62, as the network’s news anchor following the 2004 election.

Williams, the dominant on-camera presence for MSNBC--the third-rated cable-news network--will become the first person to anchor a major network without any significant reporting experience. Other than a brief stint in NBC’s Washington bureau, Williams’ entire career has been spent on local television stations and in cable news, where over the last few years reportage has given way to attitude and correspondents have been replaced by a series of interchangeable ranting heads.

To his credit, Williams professes a total commitment to hard news. His employers, meanwhile, promise two years of remedial education in interviewing and international reporting. It is all a rather long and dreary distance from the days when years of distinguished domestic and foreign correspondence were prerequisites for aspiring anchors. But serious analysts of broadcast news’ distressing state think the Williams moment was inevitable because television anchors with extensive reporting experience are vying for a spot on the endangered species list.

“In many ways, the networks today are all front office and no bench,” says Martin Kaplan, who directs the Norman Lear Center at USC’s Annenberg School for Communication. “A generation ago, a network correspondent could have gone from bureau to bureau across the country and around the world gaining experience. But years of corporate consolidation and retrenchment have left the networks with one correspondent in London, who covers all of Europe and probably North Africa, too.

“With those exigencies at work, the only place from which a TV journalist can emerge is the local affiliate,” says Kaplan. “And when you look at what local news in America is like, it’s clear it’s just a desperate attempt to grab people’s attention. Appearance, which is one of Williams’ strengths, is certainly one way to grab attention.”

Kaplan thinks Williams may be the perfect anchor for these times in which baby boomers may still care about networks and anchors, while younger viewers may not need an institutionalized father figure. “What the young seem to need,” he says, “is quick fixes of infotainment. For them, boredom is the biggest sin, not ignorance.”

When it comes to literature, what the young seem to need is a good long look into the mirror of self-regard. That, at least, is what is suggested by forthcoming titles in “young adult fiction,” geared to readers between 13 and 17.

Young adult is a category that now attracts serious literary writers, the latest of whom is the improbably prolific Joyce Carol Oates. Her novel, “Big Mouth and Ugly Girl,” depicts the friendship of a female high school athlete, “a loner,” who comes to the defense of a boy who foolishly jokes about killing people at school. The story is loosely based on a series of such incidents that followed the killings at Columbine High School.

“There’s always a moral in my writing,” Oates said in a recent interview, “although it’s not necessarily explicit. These young people are made to realize certain flaws in their personalities and characters, which we all can learn.”

Oates said she believes teenagers are “looking for stories about their own lives, ways to behave and analyze emotional situations.”

Scholastic, awash in the profits from its Harry Potter series, apparently agrees. It plans four young adult books for its new PUSH imprint, and their subjects include self-mutilation, eating disorders, drugs and arson.

“Kids, like all the rest of us in American society, are given to navel gazing,” says Marc Aronson, a longtime editor of young adult books and author of “Exploding the Myth: The Truth About Teenagers and Reading.” “But, ‘What does this have to do with me?’ is not a question this generation invented. In this, adolescents’ reading habits have become most similar to confessional television and the memoir vogue in adult publishing.”

And while what Aronson calls “the overly elaborated problem novel with a ‘bibiliotherapeutic’ aim” has come to dominate the genre, he believes some publishers are losing sight of another “vibrant strand of interest” that leads teenagers to seek experiences apart from their own. “There is a kind of mantra among publishers,” Aronson says, “that kids want to read only about themselves. So, there is reflexive bowing to the god of realism. But the success of ‘Harry Potter’ proves that kids want to read about a world that isn’t their own, one that is heroic, as in Tolkien.”

David Halberstam is the author of 18 books, most recently “War in a Time of Peace” and the forthcoming “Firehouse”: “I’m deeply engaged in something I’ve wanted to do for a long time, which is a book on the Korean War. Its focus is a battle fought at Thanksgiving time, 1950. There was a terrible miscalculation on the part of Gen. Douglas MacArthur and others, and American troops were sent to the Yalu River in arctic temperatures, there to be hit by Chinese forces, who outnumbered them roughly eight to one--terrible odds. In the days that followed, you have the heroic march of the First Marine Division out of the Chosan, while the Army’s Second Infantry got smacked. A shooting war with the Chinese began, the Cold War deepened dramatically and bad things happened as a consequence.

“My working title is ‘The Coldest Winter.’”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.