Wisconsin’s Tale of Two Performance Centers

APPLETON, Wis. — From Los Angeles to Miami, theaters are clamoring for the first national tour of Mel Brooks’ “The Producers,” the biggest Broadway hit in years. No Chicago-area theater has yet announced a booking, but it’s already on the 2002-03 slate for the new Broadway season in Appleton, Wis.

Appleton?

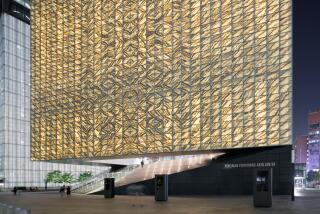

Despite a population of only about 70,000, a downtown struggling for life and a state government that has refused to help, a coalition of corporate boosters from this little college town somehow has managed to finance the kind of massive and opulent new downtown performing arts center usually found only in large cities.

Appleton, the birthplace appropriated by Harry Houdini (who was actually born in Europe), the burial ground of Joseph McCarthy and the hometown of Lawrence University, will make a full frontal assault on Green Bay’s long-established role as the area’s cultural headquarters when the arts center opens this fall. The rivalry is evolving into a juicy drama here, where the brutal winters make the population as passionate for the arts as for the Green Bay Packers.

The Fox Cities Performing Arts Center will seat more than 2,000 people and ultimately cost in excess of $45 million--$38 million of which has already been raised through the collaboration of a paper products company, a fraternal benefit society and a car dealer, all eager for a cultural lure to attract and retain employees.

“We’re building a Lambeau Field for the arts,” says John Bergstrom, a local automobile dealer and the president of the center’s board of directors. “This community is getting to show what it’s made of.”

Indeed, if Appleton’s frisky leadership gets its way, when it comes to a night out, traffic will soon be flowing out of blue-collar Green Bay (population 103,400) and heading 28 miles south to Appleton.

“The night when this theater opens will be a defining moment for the future of Appleton,” says Tim Hanna, the town’s cherub-faced mayor. “People will no longer be able to say, ‘Why would I want to move to Appleton? There’s nothing to do there.’”

None of this sits well with Green Bay, which already has a spiffy performing arts center that’s almost the same size as Appleton’s. Built in 1993 at a cost of $19.4 million on the campus of the University of Wisconsin-Green Bay, the Weidner Center offers the same mix of Broadway, classical music, pop acts and light entertainment as the one projected for Appleton.

The Weidner Center has about 10,000 subscribers. And because a quarter of its customers come from the Appleton area, it is not pleased to see the new competition.

“The new building is almost identical to ours,” says Weidner Center executive director Tom Gabbard. “This is a small community. And even though there’s been a rivalry between Appleton and Green Bay for generations ... , this is really all one market.”

But fortunately for the Appleton boosters, the Weidner Center is not affiliated with any of the large corporations that run the Broadway seasons in most major American cities. It is an independent, nonprofit presenter. The Appleton center, on the other hand, will be partnering with Clear Channel Entertainment, one of the biggest producing and presenting firms.

In the past, Clear Channel has had to send its shows to the Weidner Center to get access to the lucrative Green Bay market. For its part, the Weidner Center thought it could do better by combining Clear Channel shows with others and doing the presenting by itself.

But as it has shown in other areas of the country, Clear Channel much prefers to control both the product and the venue. And once it has both pieces in place in a given market, it has a history of freezing out independent arts centers.

By signing a contract with Clear Channel, the new Fox Cities Performing Arts Center will benefit from Clear Channel’s clout to get Appleton most of the big, profitable shows, including “Mamma Mia” and “The Producers” and the many pop and rock acts in which Clear Channel has an interest.

The Weidner Center is clearly in trouble.

“We have waited patiently for this new facility to come together in a great market,” says Scott Zeigler, who runs Clear Channel’s North American operations from New York, “and we feel very strongly that whoever controls the product will do very well there.”

“It remains to be seen how all this will shake down in the marketplace,” says Gabbard. “They have their building to run, and we have ours.”

Gabbard also said he will try to persuade Green Bay residents that the money they spend at the Weidner represents local support.

“We live in this community and put all our profits back into the community,” Gabbard says. “Clear Channel takes them out of town.”

Still, the entertainment business operates on a national scale. Zeigler said he has already been working hard to convince other producers that the Appleton theater is their best option for the Green Bay market. And when a bidding war erupted between the Weidner and Appleton theaters for the lucrative tour of “Mamma Mia,” Clear Channel won the deal by offering incentives in one of its other markets on the West Coast. The Weidner Center cannot compete with that.

The deal with Clear Channel was not the only strikingly savvy part of the Appleton development. While most of the cultural facility development in downtown Chicago has required taxpayer subsidy, Appleton’s corporate leaders have done it largely themselves.

Philanthropy aside, Aid Assn. for Lutherans and Kimberly-Clark, both big organizations with a major presence in Appleton, had a specific reason for coming up with the money to get this new building off the ground: the need to recruit and retain choosy employees looking for nighttime activities during the long winter.

“This was a very good business decision,” says Alyce Dumke, director of community relations at the Aid Assn. for Lutherans, a fraternal benefit society that plunked down a startling $8 million to get this project rolling (and that temporarily loaned Dumke herself to the fund-raising effort). “The more vibrant a community becomes, the more you can hire and retain quality talent.”

“We have outstanding schools and hospitals,” says Kathi P. Siefert, an executive vice president at Kimberly-Clark in Appleton, where the corporation has 6,000 employees. “But our people have told us that we also needed something like this.” Kimberly-Clark came up with more than $2 million.

The local movers and shakers took this core funding and persuaded others to join the list of givers. The group also successfully talked local hoteliers into supporting a room tax aimed at raising between $5 million and $8 million from out-of-towners. The city of Appleton agreed to pay for the infrastructure on the site--a commitment worth close to $4.2million. Still, the perception locally is that the center is a private corporate gift to the community that will revive Appleton’s downtown.

“This used to be such a thriving downtown,” says Sharon Hibbard, who has tended bar for almost 25 years at Cleo’s, a tavern just down the street from the construction site. “Everyone is jumping on the arts center bandwagon now. They’ve even opened a martini bar across the street from there. For Appleton, that’s different.”

“People told me I should get out front with this center,” said Mayor Hanna. “But I said I wasn’t going to let this be perceived as a government project. If it had been perceived as a government project, it would have failed.”

“We needed to be able to tell people that they were not going to see this center on their taxes,” Sie- fert said. “We want this project to support residents of this community, not hurt them.”

For Appleton’s semiprofessional Fox Valley Symphony, the new center is musical manna. And the new presence will allow the local orchestra to spend less time looking enviously northward at the larger Green Bay Symphony.

“This will allow us to expand our artistic goals,” says Brian Groner, the orchestra’s part-time music director and a man still getting used to the idea of having such opulent surroundings. “Right now we’re making sure we can fill up that huge stage in terms of bodies and instruments.”

So will Appleton’s center have the support to survive?

There’s still $7 million to be found in capital costs--and the problems won’t end there. Even in far larger markets, most comparable arts centers do not bring in enough money at the box office to pay their overheads.

Bergstrom says he’s not worried about the rest of the fund-raising. The residents of Appleton, he says, are rising to the challenge.

“A fellow gave us $500,000 just last week,” he said.

Furthermore, the proud corporate parents of the center all say they fully expect the venue to need an operating subsidy each year, and that they will raise the funds.

They also point to the combined population, more than 350,000, of the cities in the local media service area--including Oshkosh, Menasha, Neenah and Appleton. Moreover, they say similar new projects elsewhere have generated an increase in the pool of buyers for arts and entertainment.

Already, nearly 7,000 subscriptions have been sold to Broadway in the Fox Cities.

Kirk Metzger, Appleton’s newly hired executive director, says he hopes his operation and the Weidner can “stay out of each other’s way as so as not to drive up the costs of entertainment.”

Still, Appleton clearly will need to pull a fair percentage of its audiences from Green Bay to survive.

Either way, the artistic face of this part of Wisconsin won’t ever be the same.

“To a large extent, Clear Channel came and this center got built because of our success,” says the Weidner Center’s Gabbard. “I suppose we only have ourselves to blame.”

Chris Jones is an arts reporter for the Chicago Tribune, a Tribune company.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.