Peddling His Wheres

SAN FRANCISCO — How many of you working stiffs, like me, stay freeze-dried to your office seats each day while dreaming of the Great Escape? You know, handing back the 9-to-5 job, thank you, selling the house, cashing in the 401(k) and risking that grand global adventure?

If you’re weak-willed like me (my wife would say--aaaack!--responsible), you submerge your wanderlust by reading travelogues and adventure novels while slouching off each summer on a three-week, over-in-a-heartbeat international vacation.

I’ve never had the chutzpah to utter those famous Johnny Paycheck lyrics, “Take this job and,” well, you know.

Then, the other day, I met someone who did just that.

I was wolfing down lunch at my desk when a colleague roused me from my workaday routine. “A man at the door wants to talk to a reporter,” she whispered. “He says he’s riding his bicycle around the world.”

I shook hands with Richard Gregg. Within minutes I realized I was standing face to face with the man who personified my longings for emotional and physical flight. In 1990, this soft-spoken adventurer walked away from a dreary engineering job in his native England to begin a (so far) 12-year odyssey, pedaling 25,000 miles across Europe, Africa, Asia, Australia, Oceania and, now, the Americas.

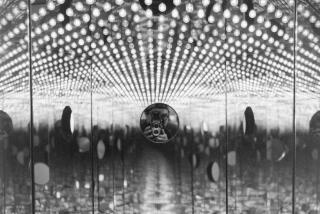

Taking his own pictures, often lingering to capture the spirit and pace of a city, village or crossroads before cycling on, Gregg chronicles his travels on his Web site, www.worldcycle.org.

As he describes his journey in one of his reports, he has “dealt with Tibetan wolfhounds, British Telecom, Egyptian camels, Chinese shopkeepers, Indian paperwork, Sudanese spies, Tanzanian baboons, Vietnamese money-changers, salmonella typhoid, Italian drivers, Pakistani amoebae, drunk Ugandan gun-waving check-post-guards and Kenyan mosquitoes, and survived, albeit with varying levels of success.”

Now here he was in San Francisco, talking of youth hostel accommodations, biking this city’s killer hills, and his recent arrival in the Port of Oakland by way of container ship from Fiji.

And a thought occurred: If I can’t join him, perhaps I can at least host him. After a call to my wife (“Honey, can I bring home a perfect stranger to skulk our flat each night as we sleep?”), I invited Gregg and his fully panniered, 125-pound packhorse of a touring bike to stay with us for a week or so.

Captivated by his easygoing style and quirky Inspector Clouseau mannerisms, and the way he feigned an American accent in response to hokey TV ads, I gave Gregg the keys to our place and set about trying to learn what I could from this wanderer about life on the other side of the cubicle.

What I wanted to know was this: Why do some people choose to live out their lives within a few miles of their birthplace while others clamor to escape their roots in an evolving effort to reinvent themselves? And do those like Gregg, who have refined the art of travel into something of a slacker lifestyle, envy anything about those of us who remain rooted?

Gregg, who refers to himself as ICBM, or Inter-Continental Bicycle Man, cycles for no cause other than simple adventure. He prefers to steer clear of politics except where necessary, instead weaving tales of adventure and friendships made along the way.

He dreamed of travel even as a kid. “When I was 8 years old I had to copy an encyclopedia picture of the Taj Mahal at school,” he writes. “I made up my mind to go to see it for myself. My 7-year-old sister, at about the same time, showed me a Japanese pen pal’s picture postcard of Mt. Fuji. I asked her about it, and she said it was an exploding mountain. I would definitely go and see that, I decided.”

Japan continues to corner his imagination. In the course of his bicycle journey, Gregg met his Japanese wife, Haruyo, in a bus station cafe in Laos.

At her request, he’s trying to wrap up his global circumnavigation within the next year and plans to ride across Canada, the U.S. and South America. Then it’s back to Japan--where he has already spent more than two years teaching English--to settle down with his new wife and, perhaps, raise a family.

He plans to one day write a book describing the unfettered freedom of a make-it-up-as-you-go itinerary that includes tracking the Nile upstream to Aswan, where two British cycling mates used tennis rackets to deflect the rocks hurled by mischievous Egyptian boys.

He has pedaled through the Sudan and Uganda and into Kenya, down the Great Rift Valley, to Nairobi and Mombasa. According to Gregg’s online bio, he’s cycled through India and Pakistan and ridden across China from Tibet to Beijing, cranking over the Himalayan range by the Nepal-Tibet route, where, on downhill jaunts, bees struck his bike helmet like bullets. He also had an extended yearlong break because of a torn ligament in his knee sustained when he stepped into an opening in the deck of a houseboat in Kashmir, India.

He was in Hong Kong for the British hand over of power to China. He spun his cranks through Vietnam, Laos, Thailand and Malaysia, clear to Singapore, across the bleak heartland of Australia, where wise guys in a passing truck threw a beer bottle under his tires.

In Fiji, he said, when he told a policeman his name, the officer observed: “Oh, like Richard the Lionhearted.”

Gregg didn’t relish the comparison with the ancient marauder.

“Hey, it’s part of history,” the officer said. “We used to eat people around these parts. And nobody here wants to talk much about that either.”

Gregg frequently gives slide shows at nursing homes. I accompanied him to a local home where he offered a dozen “rogue grannies” a glimpse into his travel-crazed psyche.

Travel means compromise, and even Gregg occasionally rues the path not taken, the one that would have provided him with a home, a career and a sense of place in society. Instead he remains an outsider, never knowing what to expect except that few things worth having come easily.

When residents cooed over his slide of a brilliant orange Kashmir sunset, he described how the scene was followed by sporadic automatic gunfire that lasted all night.

And so my friend has made his choice, for now, to leave his new wife at home and continue his adventures. Rooted to my routine, I took Gregg along on one of my own escapades: to San Quentin for a story I was reporting. As I interviewed inmates in the prison yard, Gregg struck up a conversation with a gaggle of L.A. gang members.

Charmed by his insights, they asked about English slang and British prisons. In the end, they paid him the highest in street compliments. “Yo, man,” one told him, “if we were on the outside, we’d put you in our car.”

After we went our separate ways, I tried to derive some meaning from our encounter: Did Gregg appear as some cosmic sign that I should follow my instincts and hit the road? Would I be happier that way?

But as I enter my mid-40s, for good or bad, I’ve already carved out a rock-solid self-definition. And truth be told, I don’t think I’ll ever know whether those who strike out far, far from home are any happier than those who don’t. But I do know this: I didn’t envy Gregg as he trundled off toward San Jose, unsure where he would sleep that night.

As I drove to work, anticipating a new project, deciding whether I would travel to Spain or Thailand on vacation this year, I knew what was in store for me that day, and that stability suddenly felt good.

My time with Gregg has also made me appreciate the simpler accommodations of a stationary life: Unlike my guest, I can always count on relatively clean water right from the tap, paved roads on which to ride my bike and a warm, bug-free bed to climb into each night.

And my work, I’ve decided, provides me with as many varied experiences as anyone could hope to have in one place. I guess that cliche could work as a title for Gregg’s upcoming book and for my life as well: “Wherever you go, well, there you are.”

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.