A Friendlier Climate?

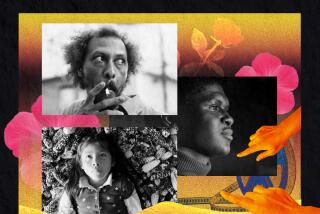

PARK CITY, Utah — Among its many functions, the Sundance Film Festival is in the business of hope. And one segment of the filmmaking population that’s sorely in need of hope is actually getting it--this is the year, or at least the moment, of the ethnic filmmaker.

According to festival artistic director Geoffrey Gilmore, 2002 is a “breakout year for Latino films.”

“This is the first time that we’ve had more good Latino films [submitted] than we put in the festival.” And there is an abundance of films by Asian Americans too, along with a couple of prominent Native Americans, although very few African Americans.

Gilmore won’t speculate why this is so--he’s been around too long to do that. Each year, Sundance features some sort of statistical anomaly that may or may not mean something--movies directed by women, movies starring Parker Posey (or Christina Ricci). What he can say is that this development is a good thing. Whether this good thing can overcome Hollywood’s resistance to ethnic films is another matter. In other words, no matter how good they are, they might not get picked up for distribution.

The bottom line for the studios is that ethnic films--even highly touted ones--aren’t proven moneymakers. Take, for example, “Girlfight,” about a teenage Latina boxer (made by an Asian American, Karyn Kasama), which shared the Grand Jury Prize in 2000 but crashed at the box office. Part of the reason for such failures lies in Hollywood’s inability to market such films, but the fact is the industry needs something to market--faces, names. White indie filmmakers have known this for a long time, larding their films with recognizable actors in order to secure funding and distribution. Whom does an ethnic filmmaker turn to when he wants to make a movie about his own community?

Arthur Dong, whose documentary “Family Fundamentals,” about homophobia among Christian families, is in competition here, says that when an Asian American filmmaker he knows shopped his project to agents and studio executives, more than one of them said, “This is great, but you don’t have any white people in it.”

Lupe Ontiveros, a critically acclaimed Latina actress, has spent much of her English-speaking career playing maids. That’s one reason why she jumped at the chance to play the theater manager in Miguel Arteta’s “Chuck & Buck,” a breakout role for her last year after playing at Sundance.

Justin Lin, whose film in competition, “Better Luck Tomorrow,” is about Asian American teenagers, says that actor Jason Tobin came to him with a sample reel of his previous roles, in which he played only delivery boys.

Of course, these stereotypes are no more or less than a reflection of societal attitudes. Patricia Cardoso, a Colombian who directed “Real Women Have Curves,” also in competition, about a Latina’s drive for independence, says she would sometimes park her car in Bel-Air and walk to UCLA, where she was going to school. Drivers would stop and ask her what house she worked for.

Sherman Alexie, a Native American who wrote the 1999 Sundance entry “Smoke Signals” and is back this year with “The Business of Fancydancing,” about the homecoming of a Native American poet, says that when he gets off a plane in a small town, people wonder what they’re supposed to do with this big, long-haired Indian, as he describes himself. He says he gets the same look when he walks into a room full of studio executives.

Perhaps inevitably, the very real stereotyping faced by ethnic filmmakers encourages them (well, at least one of them) to indulge in their own stereotyping.

“I don’t want to sound anti-Semitic [but] it’s easier if you’re Jewish,” Alexie says. “Marlon Brando [who once made the same point] wasn’t all that wrong. In proportion to the national population, whatever it is, it’s disproportionate, it’s a family business. How do you get into the family? How do you get into any tribe?”

One avenue is to make documentaries that attract what one filmmaker describes as “white guilt money” from liberal corporate and nonprofit benefactors. Few of these filmmakers would turn down this kind of money if it were offered.

.

Nor are these filmmakers above using their ethnicity to aid their careers, albeit uneasily. Bertha Bay-Sa Pan, whose “Face,” about several generations of Chinese American women in New York, is in competition at the festival, won a Directors Guild Award for best Asian American filmmaker. “There is attention put upon me because I’m Asian and female,” she says. “If it’s to my advantage, why not take advantage of it? We all have different advantages. You use whatever you can use.”

Pan thinks her film is very commercial, so much so that she was surprised to be accepted at Sundance. But it’s automatically considered outside the mainstream--and therefore independent--by virtue of the fact that it is by an Asian American and about Asian Americans. And these are not Asian Americans as often depicted by Hollywood: delivery boys or obedient daughters. One character, for example, abandons her child.

Lin’s film “Better Luck Tomorrow,” as described by Gilmore, doesn’t feature “archetypical nerds or good boys.” “I feel like it confuses the viewers,” Lin says of his movie. “The one big comment we get is that these characters could have been anybody. That’s the struggle for Asian American filmmakers. I wanted to deal with issues of teen violence and angst from an Asian American perspective.”

*

Aiming for Accurate Portrayal of Indians

Chris Eyre, a Native American who directed “Smoke Signals,” returns this year with “Skins,” about a Sioux Indian reservation policeman and his alcoholic Vietnam veteran brother. In movies, Indians fall into two camps, Eyre says. They symbolize spirituality or politics: the noble savage or genocide victim. Eyre would rather portray Indians as they really are, he says.

“They have greater iconic value in American culture than any minority, but they are people,” Eyre says. “Self-representation of Indians is one of the last cinematic frontiers left. Most other ethnic groups have forged their own territories.”

Unlike white filmmakers, who can create, say, a white sociopath without worrying that audiences will think all whites are sociopaths, ethnic moviemakers often feel they have to be mindful of the images they project. Because there are so few of these images, each one is loaded. Cardoso says she had to moderate the attitudes of her heroine’s parents--initially, neither wanted her to continue her schooling--lest audiences think all Latino parents are that way

Latino director Miguel Arteta, whose film “The Good Girl” is in this year’s festival--and got picked up for distribution by Fox Searchlight--says he took some heat, ironically, from the white community, for his depiction of a Latino gigolo in his first Sundance entry, “Star Maps” in 1997.

“I’ve never felt like I’ve wanted to make myself a spokesman for the Latino world,” Arteta says. “I think the most radical and politically correct thing to do is to do the most personal stories.”

And so after “Star Maps,” Arteta made “Chuck & Buck,” featuring a white protagonist’s homoerotic fixation on his white childhood friend.

A personal story is always going to be a tough sell, no matter who you are, says Alexie.

“If you want to be independent, be independent,” Alexie says. “The second you feel like you deserve a large audience, you’ll start making junk.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.