A Field of Glory, and Pain

Bill Stanfill, who played defensive end, can’t turn his head more than a few inches because of fused vertebrae in his neck. When he puts his car in reverse, he says, “I ease back until I bump into something.”

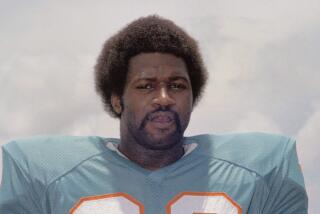

Teammate Manny Fernandez, a defensive tackle, has given up tennis, handball, golf and running because of chronic pain in his knees. “I can walk,” he says. “That’s about it.”

Larry Csonka, the hard-charging running back on that same 1972 Miami Dolphin football team, never takes off his Super Bowl ring: A mangled knuckle won’t allow it.

Nick Buoniconti, the star linebacker, gets around on a titanium hip.

They achieved perfection on the field with a 17-0 record, the only undefeated season in the history of the National Football League. But almost 30 years later, many of the ’72 Dolphins are paying a steep price for the sacrifices made in the name of winning.

They represent a side of pro football invisible to the 80 million fans who will tune in Sunday to watch Super Bowl XXXVI. They live with pain and, in some cases, disability. Broken-down body parts serve as reminders of the beatings they took: reconstructed knees, replaced hips, sore backs, torn-up shoulders, stiff necks, bum ankles, bent arms and crooked fingers.

Remembered for their grit and grace on the field, they are growing old before their time. Some limp when they walk, ache when the weather gets cold or struggle to enjoy simple pleasures like playing a game of catch with their children.

In their stiffness and pain, the former Dolphins have plenty of company. Johnny Unitas, arguably the greatest quarterback in NFL history, can barely use the right hand with which he rifled passes for the Baltimore Colts. Jim Otto, a rock of consistency during 15 years as center for the Oakland Raiders, has seen his body chipped away by 40 surgeries--30 on his knees, both of which have been replaced.

Such long-term damage reflects football’s violent nature and its tradition of playing while injured. Battered bones, joints and muscles were not given time to heal. Instead, they were subjected to fresh pounding.

“Guys played hurt,” said Sonny Jurgensen, the Hall of Fame quarterback for the Washington Redskins who played in the NFL from 1957 to 1974. “You were letting your team down if you didn’t play hurt.”

The risk of injury is just as great today.

“As players get bigger, stronger and faster, the impact of injuries certainly is not going to go away,” said Dr. Rob Huizenga, an assistant professor of medicine at UCLA who was team doctor for the Los Angeles Raiders from 1983 to 1991. “People are still playing in pain.”

The biggest differences from 30 years ago, Huizenga said, are improved surgical techniques and rehabilitation. In the 1970s, a knee injury could end or significantly diminish a player’s career. Today, he could return from surgery that same season.

But players still risk the kind of long-term damage that has hobbled the ex-Dolphins. Faster recovery from surgery means players return sooner to the game’s jarring collisions. “I’m not sure we’ve made any advancements over the long haul,” Huizenga said.

Many Players Show No Sign of Bitterness

Remarkably, many of the ’72 Dolphins express no regrets. No evident bitterness taints their memories of that glorious season, which culminated in a 14-7 victory over the Redskins in Super Bowl VII at the Coliseum in January 1973.

Fernandez, 55, who sells title insurance and lives in Cooper City, Fla., endured 12 surgeries as a player, starting in high school. But, he says, playing on two NFL championship teams--the Dolphins won Super Bowl VIII as well--made it worthwhile. “It has made other aspects of my life easier.”

His body bears the scars of eight NFL seasons: a left knee that has been operated on five times, leaving it with no cartilage; a deteriorating right knee; bone spurs in his shoulders, each of which has been surgically repaired twice; a worn-out ankle; and a back that needs a third surgery.

Bob Kuechenberg, 54, a construction consultant in South Florida, suffers from double vision. Repeated blows to the head during 14 seasons of blocking defensive linemen frayed his optic nerves.

Kuechenberg recalls having to guess which player to block during games and practices from 1981 to ‘83, his last three seasons. “You see two of them, and you don’t know which to dive at,” he said. “You wind up looking pretty foolish. I threw a cross-body block at [teammate] Kim Bokamper once, and I didn’t even touch him.”

Several eye surgeries later, he still has problems. Kuechenberg says driving can be tricky, especially at busy intersections.

“You don’t know what car’s real and which isn’t,” he said. “So I have to close one eye. At night, it’s like a kaleidoscope.”

Stanfill, 55, a businessman in Albany, Ga., struggles to get around on two artificial hips.

His neck problems started with a violent head-to-head collision with a teammate during a 1975 exhibition game. Twenty years later, vertebrae in his neck began to rupture. Surgeons fused four of the disks together to prevent further damage. His left hand has atrophied because of nerve damage related to his neck condition.

Injuries Blamed on Artificial Turf

Former defensive end Vern Den Herder, 53, supervises work on his 1,000-acre cattle ranch and farm in Sioux City, Iowa, despite searing pain that often engulfs his upper back and neck, the result of head-butting opposing offensive tackles for 12 years.

Csonka, 55, a television host for outdoor-sports shows, hobbles from chronic pain in the feet that carried him to a team-record 6,736 yards rushing.

“My toe joints took so much trauma,” said Csonka, who blames his condition on artificial playing surfaces at several NFL stadiums. “I wish I never had to play on that surface. My life would be more enjoyable.”

Safety Dick Anderson has an arthritic neck, an aching lower back and a left knee that is chronically sore. In 1975, he tore his anterior cruciate ligament, the primary stabilizer of the knee. Fearing that surgery would end his career, he played through the injury for his final two seasons.

In a 20-year span, he has had six knee surgeries, but the joint is arthritic, and he needs a seventh operation.

“When you’re playing, you really don’t think about what you’re going to feel like in 30 years,” said Anderson, 55, owner of a Miami insurance company.

Anderson’s story shows how far players would go to stay in the Miami lineup during the team’s heyday in the early 1970s. Playing in pain was--and still is--common throughout the league, but it was elevated to a high principle by the ultra-competitive Dolphins.

Many of the players relied on painkilling drugs and on quick-fix steriods, such as cortisone.

Stanfill said cortisone injections, coupled with the trauma of repeated hits, cost him his hips years later. A condition called avascular necrosis cut off blood to the bone tissue, causing it to die.

Tight end Marv Fleming, 60, who is retired and living in Marina del Rey, still feels the effects of injections of cortisone and the anesthetic Xylocaine that he received for a pulled back muscle. The shots killed the pain, but Fleming suffered a muscle tear in the same area after returning to the lineup.

“I wish I never shot it up the last time,” said Fleming, a graduate of Compton High. “Now I have scar tissue.”

Injecting cortisone directly into bone and tissue was known to cause problems, even in the 1970s, but Fleming said he had it done to treat a heel injury during the 1972 season. Fleming took a similar injection before Super Bowl VII.

“I couldn’t walk, but I was the only tight end, so I had to play,” he recalled. “They stuck the needle in . . . all the way up to the bone. They’d move the needle all around, then take it out, rub the heel a little bit and say, ‘It’s show time.’ ”

To play in Super Bowl VIII in 1974, Kuechenberg had the marrow drilled out of his broken left arm and a steel-alloy rod inserted.

‘Whatever It Took to Win’

Center Jim Langer, 53, who lives in Minnesota, played with screws in his knee. When the screws loosened, he allowed the team doctor to place a piece of wood over his knee and hammer them back into place. The procedure reset the screws but caused an old scar to split open.

“It was an attitude that whatever it took to win, we did,” said Howard Kindig, a backup center and long snapper for the ’72 Dolphins. “It didn’t matter if you were a superstar or third-string. There was one thing in mind, and that was winning football games.”

Fernandez played his first playoff game against the Oakland Raiders in 1970 with one of his arms strapped to his side with a leather harness. The device prevented him from raising the arm and further damaging a separated shoulder.

“I literally played the whole game with one arm,” Fernandez said. “It sounds kind of unbelievable, doesn’t it? Does to me too. But it seemed like the way to go then.”

An avid hunter, Fernandez has had his rifles modified to reduce the recoil and protect his surgically repaired shoulders. His damaged knees have given him the most trouble. After retiring from football in 1977, Fernandez gradually gave up recreational activities.

“Running is not even an option,” he said. Fernandez can walk on a treadmill or stair climber “as long as I don’t get too rambunctious.” He controls the pain, to a degree, with prescription drugs. He recently had to stop taking one medication because it was too hard on his stomach.

“Every day is a surprise,” he said.

Players who retired in the 1970s, as many of these Dolphins did, were not covered by lifetime medical insurance. Some applied for workers’ compensation, the state-administered programs that provide benefits to people injured on the job.

But because Florida excluded professional athletes from workers’ compensation, Fernandez, Stanfill and other Dolphins had to pay their own medical bills.

In 1990, the NFL Players Assn. won a grievance against the Dolphin organization on behalf of a group of ex-players, forcing the team to pay for health insurance.

“It took eight years of legal battles to do that, and [the Dolphins] fought it tooth and nail,” Fernandez said. “If I don’t get treated for two years, [the benefit] goes away. But that hasn’t been a problem.”

Today, retired players can become eligible for lifetime benefits by paying an annual $50 fee to the players’ association. In the 1970s, players who retired kept their NFL-provided insurance for less than a year--until the start of the next season.

“That was all you had,” said Gene Upshaw, executive director of the players’ association and a former Oakland Raider all-pro guard who played against the ’72 Dolphins. “You could file for workman’s compensation, like you could in any other job, but in ’72 players were not even thinking about [doing that].”

Pension and disability benefits have increased over the years, notably with the 1993 collective bargaining agreement and subsequent extensions.

Dolphin Organization Comes In for Praise

Despite their legal battles, Fernandez and Stanfill have nothing bad to say about the Dolphins. “It’s kind of a contradictory situation, because they do great things for us sometimes,” Fernandez said.

Among the perks has been the recognition he receives as a member of the greatest team in Dolphin history. “I’m a salesman, and the community out here has been pretty open and receptive to me,” Fernandez said. “It has made it easier to make a living.”

Becoming successful outside of football was more important for this group than for current players because NFL salaries were much lower in the 1970s.

Stanfill, selected the top collegiate lineman in the country at the University of Georgia in 1968, was the 11th pick in the 1969 NFL draft. He was paid a rookie salary of $20,000.

The most he made in a season was $125,000, and that was only after Csonka, running back Jim Kiick and receiver Paul Warfield left the Dolphins for the World Football League in 1975, prompting Miami to raise salaries to prevent further defections. Stanfill and Fernandez became the first $100,000 defensive linemen in the NFL.

Stanfill says he would do it all again today, even if it meant living with artificial hips and a neck that doesn’t turn.

“You’re damn right I would, especially at [the money] these jokers are making nowadays,” he said. “It’s because of Sundays. I loved every game and hated every practice.

“It’s because of those Super Bowls and what went on in the locker room. The pranks. The mess we could get ourselves in.”

*

Times staff writer Sam Farmer contributed to this report.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.