A View From Echo Park

In the photograph, Danny leans over the hood of his lowrider, his young face suffused with pride. Posing next to an image of Christ painted on the glossy metal surface under his chin, he appears to hold back a slight smile. Jesus looks skyward with a face full of pain. The young Echo Park man looks directly at the camera. Tattoos peeking out from under the loose-fitting threads of a born and bred pachuco, Danny is all youthful hope and handsome confidence.

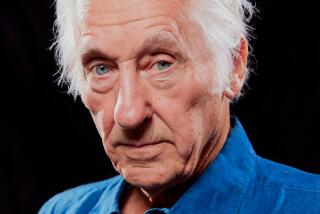

Della Rossa, 81, shot the photo at the subject’s request. “He walked across the street to ask me if I’d like to take a picture of him with his car,” she says. Two years later, Danny appears again in a photo of a family celebration at his cousin’s First Communion. Standing behind her, the shirtless cholo looks away, his upturned eyes glassy with a telltale numbness, testament to la vida loca, gang life, in Echo Park. According to Rossa, who began photographing gang families in Echo Park during the early ‘80s, Danny had already begun the downward spiral into drug abuse and crime.

The black-and-white photos, along with over 40 more taken during a 20-year period, were recently exhibited as part of a one-woman show at the Perfect Exposure Gallery in L.A. The work follows the families with uncanny intimacy. The mostly Mexican American kids seem to have dropped the veil of hard detachment that often imbues similar portraits. Rossa stays in touch with many of them, delivering copies of the photos as gifts at holidays or on birthdays.

A former print journalist who took up photography at age 60 during a class at Pasadena City College, Rossa was fascinated by the gang graffiti and the demographic transformation she witnessed in Echo Park throughout the ‘60s and ‘70s. “I wanted a challenge, so I suggested to my instructor that I photograph the entire length of Sunset,” recalls the artist.

Rossa, who was raised in Fresno, lost her father to a sawmill accident when she was 5. Only vague memories remain, she says, of the Italian immigrant who gave her a surname and an aquiline nose. Reared by her Irish mother, she made her way to San Francisco as a young adult and later to New York, where she met the man she would marry. They arrived in Los Angeles in 1957, settling in Echo Park four years later. With her working-class sympathies and experience as a journalist, Rossa often accepted freelance assignments, and though not yet a trained photographer, she sometimes took the photos that accompanied her stories. In August of 1970, for example, she covered a protest march by the Chicano Moratorium Against the War in Vietnam that erupted into violence between sheriff’s officers and Chicano civil rights activists in East L.A. Taken amid the clouds of tear gas, her images of the melee appeared on the cover of the Los Angeles Free Press and in the pages of the New York weekly the Militant, and the series was later published in a limited-edition book titled “The Day They Killed Ruben Salazar.” A copy of the book is in the Smithsonian’s permanent collection. Another sits in L.A.’s central branch library downtown. At her hilltop home with a view of downtown, Rossa is modest about the scope and impact of her latest work, discussing her subjects with a maternal affection. “I’m concerned about them,” Rossa says, adding that she has been treated with only kindness and respect by the so-called gangbangers.

On the coffee table in front of her is a more recent photo of Danny. He is thick with prison yard muscles, his face etched with the pockmarks of time, yet he has once again dispensed with the gangster’s stoic resolve. His gaze is tender, vulnerable even, and it somehow defines the power and beauty of Rossa’s photographs.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.