Researchers Seek to Trace the Mysterious Origins of Alzheimer’s

The end for the Alzheimer’s patient is a horror: The person is mute, bedridden, adrift from the thoughts and feelings that make up a life. The brain undergoes an equally disturbing transformation, shrunken by as much as half, mottled all over with hardened plaques. Where neurons used to crackle with messages, all that is left are twisted threads, fittingly referred to by scientists as tombstones.

Now, after years of work detailing this devastating finale, many scientists are turning to tracking the path of Alzheimer’s back to its roots.

They are scrutinizing how certain proteins gum up the brain mechanisms needed for memory. They’re developing blood tests and other ways to diagnose Alzheimer’s early. Researchers are even testing whether drugs such as painkillers and estrogen can prevent the disease.

For a society facing an epidemic of Alzheimer’s--an estimated 360,000 new cases each year--getting at these early stages is critical. But it’s also significant because years and possibly even decades before symptoms surface, subtle changes are already underway in the brain.

“It’s like an iceberg building,” said Dr. Dennis Selkoe, a professor of neurologic diseases at Harvard Medical School. “It takes a while until it breaks the water.”

Doctors want to find a way to intervene. But Alzheimer’s raises some of the most daunting questions in medicine because the condition takes over the human body’s most complex organ: the brain.

Thirty years ago, physicians thought Alzheimer’s was an inevitable consequence of aging. But they came to see that only certain people suffered from what is, in fact, a disease. Its hallmarks are sticky protein deposits, or plaques, and abnormal tangles in nerve cells.

By killing brain cells, Alzheimer’s causes patients--who have included Ronald Reagan, Iris Murdoch, E.B. White, Rita Hayworth and Willem de Kooning--to deteriorate to an infant-like state. Their thinking and memory erode, their personality changes and they eventually forget to feed or bathe themselves.

“We can tell you in horrifying detail all the later stages of the disease,” said Dr. Marcelle Morrison-Bogorad, associate director of neuroscience and neuropsychology at the National Institute on Aging. “Now we’re beginning to get a handle on the earliest stages.”

Selkoe’s study of rats in the April issue of the journal Nature showed which form of the protein involved in Alzheimer’s--beta amyloid--builds up in the brain. The work proves that the protein does its damage by interfering with memory circuits.

Many scientists are trying to figure out ways to pick up these and other brain changes. Researchers have already identified several genes that can cause Alzheimer’s. They have also discovered that some neuropsychological tests can reveal deficits, such as visual memory errors, in people who go on to develop the disease.

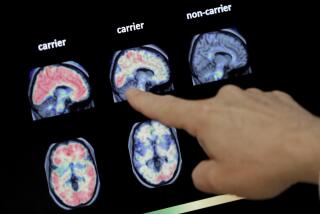

Some physicians are enhancing imaging techniques so they can see the microscopic deposits and tangles in the brains of living patients. Right now there is no way to view this destruction until autopsy.

“Somehow you have to look in there and see if the treatments are working,” said Dr. William Klunk, an associate professor of psychiatry at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine. He and Dr. Chester Mathis are testing a dye that can penetrate the blood-brain barrier and highlight the plaques during a PET scan.

In another approach, a recent study suggests that a blood test might be able to detect Alzheimer’s pathology in the brain, even before a person shows symptoms.

Dr. David Holtzman, an associate professor of neurology at Washington University School of Medicine, along with Dr. Steven Paul at the pharmaceutical company Eli Lilly, reported that intravenously injecting mice with an antibody to beta amyloid decreases the level of the harmful protein. Apparently the antibody flushes it from the brain to the bloodstream. There, the amyloid doesn’t appear to cause any problems--and can be measured.

Other scientists are working their way back even earlier in the progression of Alzheimer’s by trying to prevent it.

About 5% to 10% of people who develop the condition have the inherited, or familial, form, which means they’ll get Alzheimer’s early, between the ages of 40 and 60.

But the bulk of patients with the disease develop it after age 65. One in 10 adults over 65, and nearly half of those over age 85, have Alzheimer’s. These people’s risk is probably influenced by factors that can be changed, such as environment or diet.

One of the more intriguing avenues scientists are exploring is the complex relationship between Alzheimer’s and heart disease. According to several studies, lowered blood pressure in midlife seems to correlate with a reduced risk of Alzheimer’s later. At the same time, other research has shown that the most common type of cholesterol-lowering drugs, statins, might also decrease one’s risk of Alzheimer’s.

The findings hold out promise that treatments proved safe and effective for one major disease could be tapped for another. But experts aren’t expecting easy answers.

“We can describe things, but we can’t say how they work. Quite often our attempts to explain how they work is just sort of skating over the surface of our ignorance--not because we’re stupid but because there’s so much to know,” said Morrison-Bogorad of the National Institute on Aging. “There are huge questions.”

Scientists need to figure out why Alzheimer’s starts, where it starts, how it progresses and what can stop it. They have to decipher why some neurons are vulnerable to the disease and, conversely, what protective factors enable other nerve cells to survive.

In the meantime, to help the rest of us ward off Alzheimer’s, a stream of studies suggests such steps as doing crossword puzzles, taking vitamins and engaging in leisure activities such as watching movies.

*

Diana K. Sugg writes for the Baltimore Sun, a Tribune company.