Troubled Man Recalled as ‘Free Spirit’

In the end, the demons that besieged Timothy Wilson’s mind and the hurt that racked his body proved too strong to fight off.

He died alone at the place he called home, a ramshackle encampment in the Tujunga Wash, where the blue sky and sparkling stars were his roof and illumination.

Scattered around his once muscular body that had gone to fat were empty pill bottles for the prescription drugs he took to ease the pangs of alcohol withdrawal and the psychotic symptoms of his mental illness.

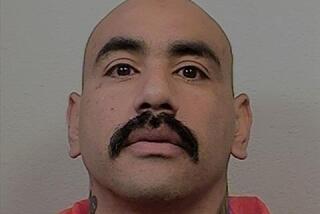

Police found him Aug. 29 on a broken-down couch, next to his blue tent, a 44-year-old man with a bushy white beard and stringy blond strands of hair shading a face sunburned from daily exposure. The red, green and blue tattoos on his arms were a giveaway to a former life of riding with the Hells Angels and Diablos biker gangs.

No one had seen him for two days at the park, market and fast-food joint that were his usual haunts. That was of no concern at first, because Timothy Wilson was a loner, a quiet man who was nicknamed Nomad for a reason.

As they gathered Sunday for a memorial service, one question for his family and friends is whether his death was natural, accidental or a suicide.

The answer, weeks away pending coroner’s toxicology tests, will hardly alter the world’s course, for Wilson was homeless, an ex-con with a rap sheet of drugs and intimidation that is ugly to contemplate.

But his death says much about the hazards of life on the street, whether on a corner in downtown’s skid row or in one of the many hidden homeless encampments that dot the canyons, freeway underpasses and riverbeds of Los Angeles. And his demise also speaks truths about how social programs that offer so much promise can sometimes fail to make a difference.

Wilson left behind family and friends who caught glimpses of a man who, when sober and stable, was gentle, funny and artistic.

“Loving, attentive, mild-spoken, intelligent, that’s the Tim I’ll remember,” said his sister Tera Lombardino, who saw her brother for the final time last Christmas when he visited her small, neat home in Lakeside near San Diego.

“He had plans to pursue his artwork; he had goals just like other people. He had made so many mistakes, and he thought maybe it was his time to get a little piece of something good.”

On Sunday, Lombardino and others shared their reflections at the memorial service held at the First Assembly of God church in El Cajon.

“Timothy was a true free spirit, and he lived the way that made him happy,” said Lombardino in a eulogy.

A friend from Wilson’s biker days spoke of how he had tried to steer his club brothers away from trouble. “Timothy taught me a lot of things about life,” said the friend, who wished to be referred to by his biker name, “Hazard.”

On his chest, over his heart, Hazard had a tattoo of one of Timothy’s favorite phrases, “Forever and a day.”

“When I met him I was a real angry person. If not for Tim, I’d be doing life in prison right now. Contrary to belief, Tim was a loving guy. All I can say is forever and a day, brother.”

Afterward, they carried his cremated remains in a procession of Harleys up into the foothills of the Cleveland National Forest above Alpine. On a rocky vista, his family and friends took turns scattering his ashes from a golden urn.

The spot was chosen, said Lombardino, because the remains of several other bikers have been scattered there.

In recent months, friends and even strangers had tried to help Wilson recover. He had enrolled in an experimental, state-funded program targeting homeless, mentally ill ex-cons, where he saw a caseworker with the Hillview Mental Health Center on a weekly basis for counseling.

His family and friends say it was too little and too late. He lost hope, they said, after he was turned down for federal Supplemental Security Income, a financial mainstay for those with mental or physical disabilities.

In an interview last spring, Wilson talked about how the SSI benefits would be his way out of the wash, would allow him to rent a place of his own, start saving for a car. Then, perhaps, he could begin to think about getting back to one of his loves: drawing and painting. Years ago, he ran a small business painting drawings and other details on bikes and produced other artwork.

“After he was turned down, he didn’t want to go on; you could see it in his eyes and body,” said Pattee Colvin, a friend who stays in a homeless encampment of scrap wood and tarp dwellings near Wilson’s tent. “He’d make little comments like, ‘I know what I’m doing; don’t worry about me,’ and he gave up.”

Hillview officials would not speculate about what might have happened to Wilson. His was a tough case, they admit. He checked in for his medication, but he didn’t want to be around groups of people. He had spurned Hillview’s offer of housing: a bunk bed at its Pacoima center, which was the only arrangement available at the time.

“The last day we saw him was regular, and he was fine,” said Hillview director Eva McCraven. “He was psychiatrically stable by our parameters. We weren’t aware of any crisis.”

McCraven said it is difficult for many patients who are drug abusers to secure disability benefits, which require a mental or physical condition that would keep a person from earning substantial wages and must last a year or longer or be likely to result in death.

Mark Hinkle, a spokesman for the Social Security Administration, would not address Wilson’s case specifically. He said being homeless or even having a history of alcohol or drug abuse does not automatically disqualify applicants if they have a legitimate disability.

But Hinkle added that even someone with a diagnosed mental illness might not qualify for benefits if the condition were controlled by medication and the person could work.

Life on His Own Terms Was Costly

Distrustful of authority and anyone else’s system, Wilson wanted to live life on his own terms. But life on the streets is brutal and often short.

Many homeless men and women suffer from untreated physical ailments, in Wilson’s case kidney and liver damage caused by years of drug and alcohol abuse. He could not stand for long periods without severe pain because of an old back injury.

Few homeless people have health insurance, depending instead on county clinics and emergency rooms. Many, like Wilson, live on a monthly $224 cash welfare grant and food stamps. To be homeless and mentally ill also means to be vulnerable, to be in danger of being assaulted or robbed of the few possessions one manages to accumulate.

It is one of the reasons Wilson chose to live on his own in his remote spot.

But when he was drinking or off his medication, he was capable of violence himself.

Colvin tells of the time Eddie, a regular at the Tujunga homeless encampment, was hassling her and she threw a pot, missing Eddie and hitting Timothy instead. Before long, Timothy had beaten Eddie to the ground in a bloody heap.

“He was a very gentle person, but if you upset him he could be a nightmare,” she said.

His own family can speak about the two sides of Wilson. Mental illness afflicts several members of her family, his sister Lombardino said, including herself and her 28-year-old daughter Angel. She lives on disability but tried to do what she could for her brother, she said.

She describes a horrific childhood of abandonment, abuse and early exposure to drugs endured by herself, Timothy and another sister and a half-brother. Timothy gravitated to the outlaw life early on and was fascinated by motorcycles and the bikers who rode them.

He joined the Hells Angels and was considered one of the best cookers of methamphetamine in Southern California. But his manufacturing and use of drugs landed him in prison often, and at least 10 or 12 years of his life were spent behind bars, said Lombardino.

Wilson sank to another level in 1982, when, in a vendetta between him and another criminal, his girlfriend was beaten and decapitated, her body dumped into a river. The case drew wide publicity at the time, and two of Wilson’s enemies were convicted of the killing.

He later got married, but the union was short-lived and stormy, said Lombardino. He never had children. His niece Angel believes much of her uncle’s mental illness and drinking were a result of guilt he couldn’t exorcise about his girlfriend’s death.

Timothy Wilson called Tera at Easter to see about visiting, but she was sick with strep throat and told him she had no plans to celebrate the holiday. “We’ll do something for Thanksgiving,” she said.

But she sent him a Bible with a prayer underlined, “I believe in a higher power,” and he thanked her.

“He was working on the soul searching,” said Lombardino. “Maybe that should have been a clue to me.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.