Seismic Standards a Bitter Pill for Hospitals

A state law requiring structural improvements for older hospitals to guarantee they won’t collapse in an earthquake could force the closure of marginally profitable institutions within the next decade, hospital industry officials say.

About half the state’s 2,700 hospital buildings at 450 sites must be reinforced or rebuilt at a cost of $10 billion to meet stiff seismic standards imposed after the 1994 Northridge earthquake.

But because fewer than half the hospitals in the state make a profit on operations, some may not be able to borrow millions of dollars they need for upgrades, which must be completed by 2008.

In Southern California alone, industry officials estimate that dozens of hospitals will close during the next 10 years, mostly because they cannot afford to meet standards imposed on older facilities.

“I would bet a month’s wages that at least 50 will be closed in this region alone,” said James Lott, executive vice president of the Healthcare Assn. of Southern California. “That’s one in five.”

The typical health care consumer may not suffer except in times of crisis, Lott said, because only half of California’s hospital beds are filled on the average day.

But to victims of accidents and violent crimes, hospital closures could mean ambulances will have to travel farther, delaying treatment.

“In many cases, this is a life-and-death issue, especially as it relates to emergency services,” said Roger Richter, the hospital industry’s statewide point man on the new law. “There really is a crisis looming out there.”

Although some experts outside the hospital industry question whether the future will be nearly as bad as that, most agree there will be hospitals that will have to close their doors.

“Some unsafe hospitals will be closed,” said Chris Lindstrom, legislative liaison for the state Seismic Safety Commission.

The 1994 seismic safety law requires 1,350 medical buildings constructed before 1973 to meet earthquake safety standards from which they were previously exempt. Although the law is distressing for hospital administrators watching the bottom line, Lindstrom still defended it as “good in terms of safety. This was not seismic safety at any cost. We tried to be reasonable.”

John Gillengerten, who helped draft the seismic rules while in government and now implements them as a private engineer, said the industry is not just crying wolf.

A state inventory of hospital buildings several years ago found that 21% were potentially dangerous, he said.

An additional 25% that were thought to be sound are turning out to be more vulnerable in seismic events than originally assumed.

“There’s a significant population of buildings out there that are not going to make the cut,” Gillengerten said.

Particularly hard-hit will be rural counties and inner-city communities, Lott said.

At tiny Ojai Valley Community Hospital, for example, chief executive Mark Turner hasn’t figured how his small hospital chain can afford to spend $3.3 million to strengthen a facility that barely breaks even.

If it closed, the nearest hospital for the Ojai Valley’s 30,000 residents would be 30 minutes away in Ventura.

“It’s a question of how do we make this investment, or does it make any sense at all?” Turner said. “I don’t know at this point.”

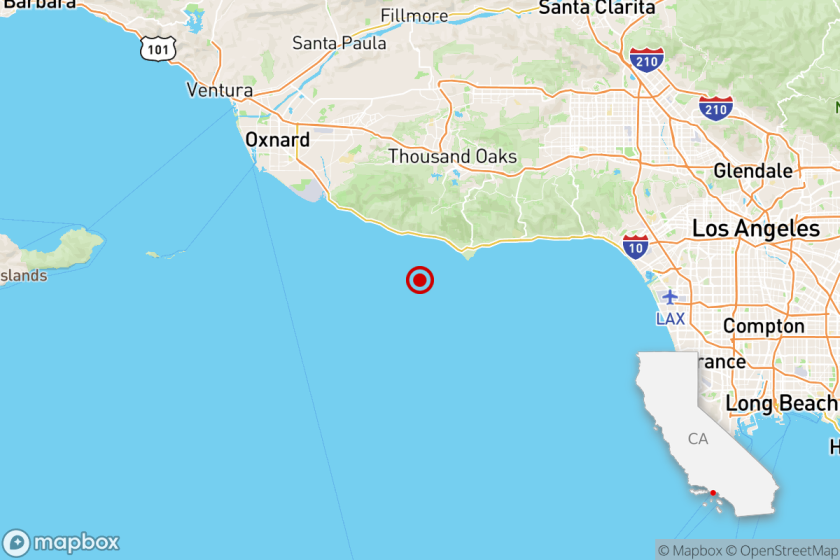

The law was passed after Sacramento lawmakers heard testimony about the predawn chaos attending the Northridge earthquake of Jan. 17, 1994.

Nearly two dozen hospitals shut down temporarily, Lindstrom said.

Some observers believe the hospital industry is exaggerating the threat, possibly to force the Legislature to act, either by allocating money for the upgrades or by extending the deadline.

Kurt Schaefer, head of facilities development at the Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development, said he was surprised by industry forecasts.

“I’ve never heard those kinds of numbers before,” he said.

Executives with larger institutions say the new earthquake law is a good thing, and that they can handle the added costs.

“It’s something we need to do,” said Kip Edwards, chief of support services for Kaiser Permanente’s 26 California hospitals. “It’s not a major shock to our system, because we’ve had a voluntary seismic safety program in place since 1990.”

Kaiser, the nation’s largest health maintenance organization, has already spent $300 million on earthquake improvements statewide, and will pay $1 billion more to upgrade or replace old hospitals by 2008, Edwards said.

Of course, some older hospitals could close, Edwards said. Kaiser is shutting down its Oakland facility, shifting patients to three nearby community hospitals.

Even without earthquake retrofitting, more than 115 California hospitals have closed or consolidated during this decade, according to the California Healthcare Assn.

That is because of sharp cuts in government and managed care payments, and a trend toward outpatient treatment, officials said. Even some surgeries once considered major are done without overnight hospital care.

Now comes seismic retrofitting, which requires that by 2008 all hospitals will be able to withstand a major quake.

By 2030, hospitals must be replaced altogether or retrofitted to such a degree that they not only stand but continue operating during earthquakes.

Industry officials estimate the cost at $10 billion over the next decade and an additional $14 billion by 2030. The $10-billion figure amounts to $15 million to $20 million per hospital.

Some hospitals would cost so much to fix they have already opted for new construction.

At UCLA, the university decided to build a new $1.1-billion medical center instead of spending a $437-million federal earthquake grant to shore up old facilities damaged by the Northridge quake.

At County-USC Medical Center, officials will apply a $468-million federal grant to replace the Depression-era structure with a smaller one costing $818 million.

But many privately owned hospitals simply do not have the resources of government and university systems.

Even some big hospital chains say seismic laws have forced them to rethink how they’re going to do business.

“We’ve been taken aback by the huge financial implication of this,” said J. Michael Gallagher, who oversees system development for 46-hospital Catholic Healthcare West.

“The closure of some facilities will be seriously considered.”

Catholic Healthcare expects to spend more than $200 million on about 30 older hospitals.

“We think a lot of buildings can be converted to other uses or sold,” he said.

Gallagher thinks the seismic safety bill goes too far and should be amended.

“People have to remember that no one was killed in a hospital in the Northridge earthquake,” he said, “but billions of dollars are going to be spent on this.”

Legislators also are beginning to realize the potential impact of the new seismic standards.

“I have no doubt that some hospitals face closure,” said Assemblyman Martin Gallegos (D-Baldwin Park), chairman of the Health Committee. “The fix is going to come through loans or grants or through exceptions or time extensions. And we’ll review those on a case-by-case basis.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.