A Road Well Travelled

From the beginning, this town was big enough for both of them.

Actually, it was big enough for 10 more like them. When Elgin Baylor, already an NBA superstar at 25, and Jerry West, an up-holler rookie from West Virginia, met on a hazy August morning in 1960 for the Lakers’ first Southern California training camp, Los Angeles barely knew they were there.

The town that had gone gaga for the Dodgers hardly cared that it had a professional basketball team. It had required neither a civic initiative nor a grant of downtown property to bring this team west, as it had with the Dodgers. This one just packed up its meager possessions and wandered in from Minneapolis. Its name was inappropriate--Minnesota was known for lakes, but why should an L.A. team be called Lakers?--but there was no outcry, or any kind of cry. The Lakers couldn’t find a radio station to carry their games until the next spring, when they got into a hot playoff series against the St. Louis Hawks and interest picked up enough to warrant hiring a broadcaster, who turned out to be the young Chick Hearn.

Can it be 37 years since these guys, aging so gracefully, first met?

West seems so urbane now, a statesman with a genteel drawl, all that remains of that high-pitched twang he showed up with, prompting Baylor to nickname him “Tweety” and “Zeke from Cabin Creek.” West would later pointedly correct the record--he was from Chelyan, which was even smaller than Cabin Creek--a suggestion that being labeled a hick had stung him, even in fun. But in 1960, he was just pleased that The Great Elgin noticed his existence.

Baylor looks so distinguished with that gray at his temples as they pose for pictures, hurrying the photographer along to hide their embarrassment. A basketball lies at their feet, ignored. For men who have lived their lives in the game, they have scant interest in the ball. Neither as much as looks at it until the photographer asks them to toss it back and forth.

“Toss it back and forth?” asks Baylor, skeptically. “Do what?”

“Heck, I’ll drop it,” says West, laughing. “We look like two damn cadavers.”

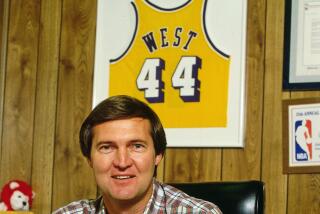

Actually, they look great, their height and natural elegance giving them the grace of models. But it’s the curse of the retired athletes--there will always be that tendency to see themselves as aged versions of famous youths. Both have made the athlete’s deferred transition into adulthood, West as executive vice president of the Lakers, Baylor as general manager of the Clippers, but though they still spend their waking hours thinking about the game, neither plays it any more. Baylor is an avid tennis player, West a voracious golfer. Perfectionists, neither could enjoy basketball at the YMCA level.

Once teammates, now rivals, but still friends. In today’s NBA, two great players on the same team are often at odds (if they aren’t, their agents may be, as with the representatives of Shaquille O’Neal and Penny Hardaway in Orlando), but it was different in 1960, before agents and everything else that goes with the modern star trip. Rather than today’s luxury cruise for overindulged post-teens and their entourages, a career in the ‘60s was a grueling survival course through a sea of indifference to see how long they could make a living at this game of theirs.

In the popular mind, West now occupies a lofty position. His profile is on the NBA logo, and by consensus of his peers, he’s at the top of this profession, too, while Baylor is saddled with the stigma of the historically futile Clippers. In real life, however, West calls Baylor often to talk about players and exchange league gossip--Baylor also once named him “Louella”--and so the relationship continues, almost as it was. If they’re no longer teammates, if life is no longer a schedule to be confronted together, they have had to overcome similar challenges: age, injury, the transition to what came after their playing careers, the joys and frustrations of their current jobs.

Running a team may sound neat, but in the NBA of the ‘90s, it’s two parts opportunist to one part bail bondsman. Even the fans’ most optimistic expectations don’t match those of Baylor and West, who burn with the same flame that made them great players. Only a peer can understand the superstar’s need to compete and dominate, and for such as Baylor and West, peers are hard to find. They were never roommates or best buddies, but 37 years later, their fondness for each other still shows.

“Pepperdine,” says Baylor, remembering that first training camp.

“I remember it real well,” says West.

“The old Pepperdine,” says Baylor.

“The old Pepperdine, over at Inglewood,” says West. “I remember it very well ‘cause I had just gotten off an airplane at noon and didn’t even go to the hotel and went to practice . . . . I got out there and started running because I had just gone from Rome [where he played in the 1960 Olympics] to Charleston [W. Va.] to Los Angeles in a two-day period. . . .

“I was whipped; I was so tired. And to get there and have this smog, I wondered what the heck it was. I mean, it hurt so bad to run up and down the court. . . .

“Coming here was an incredible adjustment for me, personally. I probably wasn’t as confident as most people I played with. And then to come here and have a chance to play in a new city, to have a chance to play with Elgin--I can’t tell you how excited I was to play with him. It’s awkward to even talk about, with him standing here.”

Playing together, of course, was just the beginning.

*

“Elgin was a motor-mouth. Elgin never shut up. Elgin knew everything--what size a 747 plane was, what horse Willie Shoemaker should be riding. He was an authority on everything. We always just laughed. . . .

See, Elgin was two years ahead of Jerry. His third year was Jerry’s first. He was captain of the team and so on. . . .

To the end, Elgin would be kind of the life of the team. Jerry developed into a leader, but very quietly.”

--Former Laker Hot Rod Hundley

*

For all his fame, Elgin Baylor could have been luckier. His career would have been even greater but for the knee injuries that began to slow him while he was still in his 20s.

He was among the elite athletes who revolutionized the game, but he was neither the first--that was Bill Russell--nor the most imposing--that was Wilt Chamberlain.

Baylor’s greatest moments came in the late ‘50s and early ‘60s, when the NBA was derided by some newspaper columnists as a “YMCA league.” But to insiders such as Mitch Chortkoff, who has been covering the Lakers for several area papers and served one season as team publicist, Baylor was “like a god.”

In his first season in Los Angeles, he averaged 35 points and 19 rebounds. At 6-foot-5, 225 pounds, Baylor was a power forward who brought the ball up against presses and delighted in going into the pivot against the lordly Russell, freezing him with fakes and shooting over him.

Baylor was a forerunner of the go-anywhere, do-anything players such as Julius Erving, Magic Johnson and Michael Jordan. But although people marveled at Baylor’s ability to “hang in the air,” he was too self-effacing to become a great stylist. Style had not become an end in itself, so he didn’t wave the ball around, pass it behind his back or through his legs, or dream up dunks for highlight shows, which didn’t exist. He just zipped past his man and scored. He scored at will, averaging 25 points as a rookie and increasing it by at least 3.5 every season until his fourth, when he peaked at 38.3 and his knees started getting sore.

Teammate Rudy LaRusso remembers his own rookie year, when the Lakers moved training camp to Ft. Sam Houston, Tex., where Baylor was in an Army reserve unit, so they could practice with him:

“We went on and played the Celtics in a 12-game exhibition tour, then played a game or two somewhere else, then were ready to open the season. Baylor flew in the night before the opening game in Minneapolis. He had practiced with us five or six days a month earlier.

“He suited up and got 52 opening night. . . . I had never seen anything like this in my life.”

Baylor had come up the hard way. He went to segregated Spingarn High School in Washington, D.C., breaking out of the prescribed pattern of the day--an unnoticed career at a small black college--only when a tiny NAIA school, the College of Idaho, offered him a scholarship, sight unseen, to play football.

After showing what he could do in basketball, he transferred to Seattle University, which he led to the NCAA Tournament. In 1958, Baylor joined a bumpkin-level NBA, still struggling with Jim Crow rules on exhibition tours in the South. Baylor’s night came in Charleston, where he was refused a room at the swanky Daniel Boone Hotel. He refused to play, making it a national story. He says he later got a letter from Charleston’s mayor--demanding that Baylor apologize.

Another time, the Lakers’ DC-3 lost its electrical system on the way back to Minneapolis in a blinding snowstorm, terrifying the players, including center Jim Krebs, who, according to Baylor, vowed never again to cheat at cards or look at stray women if they got out of this. The plane made an emergency landing in an Iowa cornfield. Of course, in the very next card game, Baylor notes, “First guy we catch cheating is Jim Krebs.”

That was Elg, life of the Laker party. He was extroverted, with a bearing that seemed to announce one was in the presence of royalty. Baylor transcended all social barriers, race included, even on a team that was just beginning to integrate and had only three black members.

“It became obvious real quick,” says LaRusso. “Elgin Baylor wasn’t black--he was Elgin Baylor. He had the respect and admiration of the veteran players that were on the team at that time. It was clear to me--he was the guy.”

It was Baylor who confronted fiery Laker owner Bob Short when NBA players threatened to strike just before the 1964 All-Star Game unless the owners provided a pension plan. Celtics Bob Cousy and Tom Heinsohn organized it, but Short came pounding on the locker- room door, demanding to see Baylor and West. Baylor came out, they talked, Short went back the way he had come, and the owners gave in.

Baylor’s legend would have been even mightier, but his knees were already going. “The ‘63-’64 season, I started experiencing unbelievable difficulty with both knees,” he recalls. “It’s very obvious if you look at my statistics from ‘62-’63 to ‘63-’64, I could not do the things that I did prior to that.”

Then, they didn’t even know enough to ice sore knees (they applied heat to Baylor’s, aggravating the swelling). He saw doctors all over, went to the Mayo Clinic, even underwent cobalt treatment once, but nothing helped. He had to be chauffeured to and from home games, because driving was so painful. Finally, in the 1965 playoffs, he went up to shoot, tore his left patellar tendon and split the kneecap.

Even though he returned to post 20-point averages in four of his last seven seasons, he couldn’t quite play like Elgin Baylor. In a sad postscript, the Lakers started their record 33-game winning streak in 1971, the night young Jim McMillian took Baylor’s place in the starting lineup.

Baylor had myriad business interests, including a string of Pioneer Chicken restaurants, but the game drew him back. He tried coaching the New Orleans Jazz, but the team was bad and it wasn’t fun. In 1980, Laker brass urged young coach Paul Westhead to hire Baylor as an assistant, which might have thrown Baylor into destiny’s path, since Westhead was fired two years later, and his assistant inherited a team that strolled to a title. Instead, the opportunity--and the ensuing career--went to Westhead’s choice, Pat Riley.

Baylor’s break came in 1986, courtesy of Clipper owner Donald T. Sterling, whom he knew socially. They genuinely admire each other (“I think many people make the mistake of underestimating just how much vision Donald has,” Baylor says), but it isn’t like the deal West has with current Laker owner Jerry Buss. Buss has deep pockets, abiding trust and little inclination to meddle; Sterling, though far richer, likes to go to committee.

It hasn’t been an easy gig. Baylor is the least visible of general managers, so loath to deal with the press that reporters have wrongly suspected his influence was waning. In 1995, for example, the Clippers, defending their controversial Antonio McDyess trade, had coach Bill Fitch call press people, which seemed to suggest it was Fitch’s deal. Actually, it was Baylor’s deal, and it’s still as much Baylor’s organization as anybody’s but Sterling’s.

It hasn’t always been fun, either, for such an old-fashioned, hard-nosed competitor. Baylor hasn’t come back to the game for a company credit card; he’s here to compete, just like in the old days, and he bristles at the Clipper jokes.

There are even moments when it seems as if it’s leading somewhere. The Clips surprised everyone by making the playoffs last season. They then drafted talented power forward Maurice Taylor. In a year, they’ll be more than $5 million under the salary cap with a chance, if things go well, to recruit a star.

“It’s very challenging,” Baylor says. “At the moment, there are things you really feel excited about, when you get a nice, young player. You want to watch him grow and develop. Other times, you get a player and he’s not the player we all thought he’d be [editor’s note: see Benoit Benjamin] . . . .

“It can be gratifying sometimes and very frustrating at other times. . . . I’m a competitive guy. I like to compete. That’s just part of me.”

*

“I really played out of fear that I was gonna fail. . . . I hated to lose. If we lost, it was always my fault, and that’s a terrible burden to take around with you. . . .

It’s something you loved to do. You just loved to do it. It was about competition. People talk about the fans, everything--I never saw the fans. I never even heard them . . . . I never looked around, and when you looked around then, it was sparse. I was so intense, it was ridiculous. I could sit in the locker room before a game--I could hold my hand out and sweat would be just dripping off. I don’t know if that’s the way an athlete’s supposed to be, but that’s the way I was.”

--Jerry West

*

One might be tempted to conclude that West has led a charmed life, if one didn’t know West.

He emerged a superstar--not in the overlooked ‘60s but in the ‘70s, when a Knick championship woke up New York and an overheated Madison Avenue heralded professional basketball as the game of the decade. He retired after 14 seasons with a 27-point career average, one of the most admired players ever, even by the Celtics. After West became the only player on a losing team ever voted series MVP in the 1969 NBA finals, John Havlicek told him, “Jerry, I love you.” At West’s 1974 retirement ceremony, before a Forum crowd, Bill Russell told him: “The greatest honor a man can have is the respect and friendship of his peers. You have that more than any man I know. . . . If I could have one wish granted, it would be that you would always be happy.”

When West got his administrative opportunity, it was with the Lakers, who already had Kareem Abdul-Jabbar and Magic Johnson. But friends who know how much West has paid for his good fortune might think twice before envying him.

West thinks about it all the time. He recently told The Times’ Scott Howard-Cooper there’s “no way” he’ll still be working in 1999 when the team hopes to move into a new downtown arena.

Of course, it’s a miracle he’s made it this far.

Typical West anecdote: It’s 1985 and the Lakers have just overcome their Celtic jinx, winning Game 6 in Boston for the NBA title. West, the new GM, has proved adept, and here he is, on top of the world, not that you can tell by looking at him. He missed the victory celebration in Boston--he thinks it’s bad luck to go on the road with the team--and now he tells a reporter that he’s not going to the parade in Los Angeles either.

“If I go to the parade,” West says, “they’ll be cheering me. I’ll be a big hero to them. And then if I make a pick in the draft they don’t like, they’ll boo me.

“You know something? I don’t need their cheers and I don’t need their boos.”

It has never been easy being Jerry West. If he seemed great at anything he touched--friends say he could play on the senior golf tour--it was because he demanded it of himself, refusing to acknowledge ever achieving it.

“Even to this day,” says Pete Newell, his Olympic coach at Rome in 1960 and his friend since, “I don’t believe Jerry really believes he’s as good as he is. He was that way when I had him in Rome and at the trials, and I think what makes him so great is that he’s never satisfied.”

Basketball was never just a game for West, it was a life’s struggle. Born in humble circumstances in Chelyan, his home was a shack, his first court a hoop nailed to a pole stuck in some packed dirt.

Almost 10 years younger than his next youngest brother, West was painfully shy. He became a basketball player, he noted in his autobiography, because it was a game “a boy could play by himself.”

The older he got, the less it seemed like “play.” He carved his pro career out of body and soul, and he didn’t so much retire as collapse from physical and emotional exhaustion.

“I had so many injuries,” West says. “I was tired of having needles stuck in me. Tired of having my nose straightened. . . . Tired of getting stitches, tired of getting my teeth replaced. Seemed like everything that could happen to a player would happen to me. . . .

“I did it [took painkilling injections] because I wanted to play, and players wouldn’t do that today and I know that. And I wouldn’t ask one of our players to do it, because it’s the wrong thing to do.”

However tortured his playing career, it was paradise compared to retirement, which, for such an arch-competitor, seemed pointless. He played endless golf. His marriage to his college sweetheart broke up. He had always worn his emotions on his sleeve and trumpeted his vulnerabilities, making him one of the most human and endearing of superstars, but now friends feared for him. “You hear about movie stars who have done it all and just go fruitcake?” former Pepperdine coach Gary Colson, a West intimate, once told Sports Illustrated’s Rich Hoffer. “I had this fear, you know, a Marilyn Monroe type of thing. What else was there? What would he do now that the cheering had stopped?”

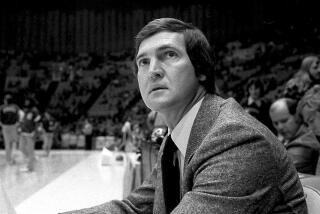

West tried coaching in 1976, but although he was successful--his first Laker team improved by 13 wins--it wasn’t for him. He didn’t like having to listen to then-owner Jack Kent Cooke’s suggestions.

He was used to being candid with the press, but his frustration with Abdul-Jabbar, a marathon runner rather than a sprinter like West, was all too evident. There were too many broken-down veterans and not enough patience, as one day when West noted: “If Lou Hudson was a horse, we’d have to shoot him.”

“I wasn’t being successful at dealing with myself, to be honest with you,” says West. “I had to do something with my life. To have the opportunity to go back to work, particularly for the Lakers, was special. And even though I wasn’t the main choice for anyone--after everyone turned down the job, I got the job. By midseason the second year, I said to myself, why am I doing this? I didn’t have control of myself personally, so how in the hell could I try to work with people and help them?”

Luckily enough, Buss, an unabashed admirer, bought the team and asked West to stay as a consultant. Three years later, in 1982, he became GM.

He is starting his 16th season. He has been voted executive of the year once, an honor some peers consider faint praise. Says Utah GM Scott Layden: “They should have Jerry’s picture on that trophy.”

Of course, West discounts the praise while insisting on paying the full toll, as last summer when the pursuit of Shaquille O’Neal left him so battle-fatigued. He compared signing Shaq to the birth of his children and later, spent, talked of retiring.

“That was the most ridiculous period of time you could imagine. I think that whole experience has probably soured me more on the NBA than anything,” West says.

“You know, we didn’t cheat to get him. If somebody even insinuates that [as the Orlando Magic did, considering, but never filing, tampering charges], that’s not much fun to contend with. You really can’t defend yourself. . . .

“[The job] does take a toll and it’s taken a terrible toll, I don’t think there’s any question about it. I’ve tried like crazy to find a way to not take it home with me, not to take it personal, but you do. Some people could do this job to infinity, but I can’t. I know that. And I won’t. . . .

“For sure I could imagine it [retirement]. For sure, I could do it. I understand the nature of the beast, but when you start to put so much pressure on yourself that you do harm to yourself and the people around you, then you shouldn’t do it anymore.

“Am I close to that point? I don’t think there’s any question. But I have two years to go on my contract. I would very much like to finish that out, and I hope I can. And I’ll see what happens after that.”

Laker staffers say he’s easy to work for and fun to be around unless he’s having one of those days, which they’ve come to understand. The Lakers work hard, but afternoons, you’ll have to reach their brass via cellular, on a golf course.

“Is Jerry the happiest man you know or the most miserable?” a friend of West was asked.

“Both,” said the friend.

*

Here they are, after 12 seasons as teammates and 25 years apart, their lives still intertwined. Each goes his own way, but it always seems to lead them back together.

“It doesn’t seem that long to me,” says Baylor, now 63 and living with his second wife, Elaine, and their teenage daughter in Coldwater Canyon. “I mean, it doesn’t seem that long.”

Says West, now 59 and living with his second wife, Karen, and their two children in Bel-Air: “For me, once you retire from playing, you’re not completely separated, but you don’t see each other every day. That’s when time seems to go by really fast.

“These jobs and everything, the nature of them--all you got to do is look in a mirror and look at old pictures. Every time someone sends me an old picture, I look at myself and I say, it’s been a long time. But it certainly doesn’t seem like almost 40 years.”

In the old days, they complemented each other effortlessly: One was a forward and played inside, the other a guard who played outside. One was confident and took charge naturally, giving the other a chance to grow into stardom.

Now they’re opponents. Each says he roots for the other, so long as they’re not playing each other.

Or unless one has something the other wants. Shortly after the photo session, the Clippers signed a young center, Keith Closs, off the Lakers’ summer league team. If West didn’t like it, he’d have to concede that’s how the game is played. Maybe Elgin will have a nice free agent on his summer league team sometime.

No, it’s not the way it used to be for Elgin and Jerry, but it’s close.

More to Read

All things Lakers, all the time.

Get all the Lakers news you need in Dan Woike's weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.