Elevating the Debate Over Cultural Power

NEW YORK — As the audience jostled its way into New York’s Town Hall on Monday night to hear playwright August Wilson debate critic Robert Brustein on the topic of multiculturalism in today’s theater, a woman was overheard saying, “If you ask me, this isn’t about race and theater in America at all. It’s about what Madeleine Albright called cojones.”

Indeed, there was more than a little macho posturing between the antagonists during their much-anticipated discussion, “On Cultural Power,” moderated by actress-writer Anna Deavere Smith. But while after 2 1/2 hours there was scarce movement toward finding a little common ground, the audience clearly relished the spectacle of two such distinguished theater figures thrashing out their controversial positions on some of the most hotly contested issues of the day--multiculturalism, political correctness and nontraditional casting.

“You have one of the great minds . . . of the 17th century,” critic and director Brustein said of the double Pulitzer Prize-winning Wilson in one of the livelier exchanges, eliciting laughter from partisans and jeers from supporters of Wilson. Brustein, a writer for the New Republic magazine, has sharply criticized Wilson in print for his speeches calling for separatist theater.

“If we do not acknowledge our very real racial differences,” Wilson replied, “we are like those people on an elevator that goes from 12 to 14 because people have a fear of the number 13. No matter what you label it, we know the floor above 12 is 13.”

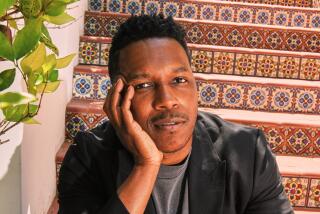

Monday’s debate stems from statements by Wilson, playwright of works that include “Fences” and “The Piano Lesson,” made last June in a keynote address before the national conference of the Theatre Communications Group, which sponsored the town hall session. The address included a fierce denunciation of what he called the racist status quo in nonprofit theater.

Noting that only one of the 66 theaters in the League of Resident Theater is an African American organization, Wilson accused black directors and playwrights of participating in “an art that is conceived and designed to entertain white society” and called for a separate African American theater. He also condemned so-called “color-blind” casting, arguing that it comes at the cost of “our own humanity.”

Brustein, artistic director of the American Repertory Theatre in Cambridge, Mass., immediately lashed back in an article in the New Republic, attacking Wilson’s positions as regressive echoes of 1960s Black Nationalism. He also took issue with Wilson’s veiled allusions to Brustein as a racist because he had written that he fears state-subsidized multiculturalism could result in a lowering of artistic standards.

Throughout the debate Brustein appeared polished, articulate and cerebral, taunting Wilson to “modify” his positions and challenging that if he really wanted to support black theater, he might do so by giving a deserving theater the world premiere of one of his own plays--a dig at the fact that Wilson’s work has been nurtured in the same theaters he is assailing.

Brustein also rejected Wilson’s characterization of him as “the enemy of multiculturalism.” “I approve of it so long as it is not a pretext for promoting racial hatred and separatism. True diversity comes from the acknowledgment of every human being as an individual, inclusion not exclusion, integration not separatism, Martin Luther King not Louis Farrakhan.”

Dismissing the critic’s taunt to modify his positions, Wilson was poetic, impassioned and, at times, defensive. “We make no apologies for our duties,” he defiantly responded, including among them the rejection of a “single white Eurocentric-based value system.”

“For too long, blacks have been given a visiting pass [to participate in the making of theater], a pass that usually expires on March 1, the day after Black History Month ends,” Wilson said.

“Assimilation under such circumstances would be harmful,” he said. The fight is simply for the right to participate in the making of theater, with control in the hands of blacks, for a change. “We are not talking about ideological art; we are talking about participating,” he said. “Not for blacks only, which would be socially unacceptable and morally reprehensible, not as separatists but simply as people who wish to be included.”

At the closing bell, Smith asked the pair: “What did you learn from each other?” Replied Brustein: “That behind Mr. Wilson’s anger, there’s a teddy bear.” To which Wilson replied, cuttingly, “Oh, I assure you, I’m a lion.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.