He Has the Right to Die, but He’s Too Busy

The headlines had concerned the right to die. For the first time in American history, a federal appeals court had ruled, by an 8-3 margin, that a mentally competent, terminally ill adult has a constitutional right to have a doctor’s assistance in hastening death.

“Dad, you’ve got to add a chapter,” Jeff Horn told his father on a visit home.

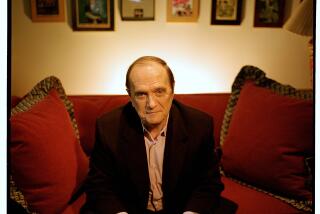

Or maybe Robert C. Horn, a retired political science professor at Cal State Northridge, could just tweak his manuscript here or there to expand on his thoughts about assisted suicide. On this moral issue, it’s hard to underestimate his opinion.

Some readers might remember Bob Horn. I’ve written about him before.

Bob has amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), a terminal disease that has left him virtually paralyzed, unable to eat, talk or even breathe without assistance. If he ever became convinced that his life is no longer worth living, he’d need somebody’s help to find the exit. Horn believes everyone in his circumstances should have that right.

He also wants everyone to know that, all considered, he’s doing just fine. In fact, there’s a good chance you’ll see Bob’s book on the shelves this fall.

The title was his idea. The publishers love it. They figure it’s a grabber, and it captures the author’s irreverent sense of humor.

“How Will They Know If I’m Dead?”

*

Yes, that should grab them, and the subtitle will explain what it’s all about: “Transcending Disability and Terminal Illness.” At this, Bob Horn is an expert.

My first encounter with him was through a letter Bob had written two years ago responding to a column about a woman who had ended her terminally ill brother’s suffering with an overdose of morphine. At the Horns’ Winnetka home, I saw how Bob would, as he put it, “kick out” his correspondence. Although ALS, also known as Lou Gehrig’s disease, had rendered him inert and had forced him to breathe with a ventilator since February 1991, he still had some strength in his thighs, enabling him to lift his legs. With a specially rigged computer mouse and a program that presents the alphabet on a chart, he could write about a page a day.

He also retained some control of his facial muscles. A small smile often curled his lips and he would often arch his eyebrows. This is important--a “yes” signal that enables his wife Judy to painstakingly find the appropriate letters on the grid. Fortunately, Bob is pithy by necessity and witty by nature.

Here’s how the manuscript’s page of acknowledgments begins:

“You should write a book.”

If I had a penny for every time someone has said that to me over the past three years, I bet I’d have at least a dollar! Maybe even a buck-fifty!

Then he gets serious, explaining that he already knew that a book is no small task, having written an academic tome on Soviet-Indian relations.

The bottom line is that you better have something of interest and/or importance to say. If you don’t, it is not worth writing; if it is written, it is not worth publishing; and, if it happens to be published, it won’t be worth reading.

I believe I have something to say.

This reader agrees. When I took his manuscript home, I spent three hours reading Bob’s words. It’s partly autobiographical and partly a how-to manual for people with severe disabilities. It is mostly a work of everyday philosophy, with a message for people who face a major illness. Bob writes of the importance of having a positive attitude--of focusing on what he is able to do, not what he is unable to do. He quotes another ALS patient: “I am convinced that life is 10% what happens to me and 90% how I react to it.”

Bob frankly discusses his episodes of depression and despair. But, he writes, there is a fundamental choice: You can either cope with problems. Or you can mope.

I have been coping, battling if you prefer, with ALS for just over seven years now. I have had virtually no functioning muscles for five years. And I have been hooked to a ventilator for the past four and a half years. These are not longevity records and my situation is far from unique. So what is my message? It is simply this: I have found, along with many others, that despite the difficult conditions of disability and terminal illness, life can be meaningful, productive, fulfilling, rewarding and valuable.

*

This time, Judy wanted to be sure I’d get to meet Gretchen Keeler. Gretchen and her husband, Bruce, befriended the Horns at Northridge United Methodist Church. In the early stages of the disease, Judy and their three kids had a hard time taking people up on their offers of help. But as Bob’s condition worsened, help was gratefully accepted.

Without Gretchen’s help, the Horns say, Bob would have had a much more difficult time producing his manuscript. He’s given her the title of “administrative assistant and literary advisor.” Bruce Keeler, meanwhile, is “director of player personnel” for Bob’s fantasy-league baseball team.

Recently, Bob wrote a memo, praising the Keelers for jobs well done and drolly announcing that he was doubling their salaries . . . from zero to double zero.

Like most authors, Bob received his share of rejections before serendipity helped his book find its publisher. Judy explained how her old high school boyfriend, a professor like her husband, helped them find a publisher. She saw him at a class reunion and gave him a copy of the 150-plus-page manuscript. He read it in one sitting and recommended it to a friend whose work had been published by St. Lucie’s Press. Health care is one of the firm’s specialties.

Amid the good news, there has been some bad. In recent months, Bob’s disease has progressed, leaving him with somewhat less control of his facial muscles. Occasionally there’s an involuntary twitch in his eyebrows. “It’s frustrating, to say the least,” Judy said. “I think Bob is having an easier time dealing with it than I am.”

But Bob still kicks out his opinions. On his computer screen this day was a letter to an Oxford University Press editor who had asked him to critique a proposed textbook on Russian politics. Next up is a book review for an academic journal in Canada.

When I asked about assisted suicide, Bob’s opinion was unchanged. But he did have something more to say. Slowly, with Judy’s help, he spelled it out.

“I believe that everyone considering euthanasia should . . .”--we were hanging on every word, waiting for a jewel of insight--”. . . read my book.”

And thus, with a smile, Bob Horn’s version of a book tour had begun.

Scott Harris’ column appears Tuesdays, Thursdays and Sundays. Readers may write to Harris at the Times Valley Edition, 20000 Prairie St., Chatsworth, CA 91311. Please include a phone number.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.