Adrift in a City of Dreams

Everyone knows we’re a city of dreams. People come to L.A. from all over the country with bundles of hope tucked under their arms, waiting for the spotlight to swing their way and bring them the fame they dreamed about back in Omaha or Lansing.

The bundles I’m talking about are screenplays. About 27,000 are registered each year with the Writers Guild by people who believe they’ve got a story to tell and there’s no better place to tell it than on a big screen.

Damned few screenplays ever get produced, but that’s OK. Every man or woman who gets off a Greyhound bus from back somewhere has heard about those who do make it, bringing new writers thousands of dollars in cash and first-class tickets to Paradise.

I get asked a lot to talk to people who’ve written scripts or to read their works, and most of the time I say no. I don’t know enough about writing to give advice. But every once in awhile I’m reeled in like a fat trout by bait too tempting to ignore. That’s why I bring you Josephine.

I was introduced to her by Chaplain Telly Miller of the L.A. Mission, a place littered with dreams that never made it. He said he knew a woman who used to be a lawyer and was now on the streets, not because of booze or drugs but because of conscience.

What happened, he said, was she represented a man back in Michigan who, after she’d won his case, went out and raped someone. She was so traumatized by it that she gave up her practice and headed west. She was living in a homeless shelter and trying to write for the movies.

It had column written all over it.

*

I met her at a Skid Row coffee shop called Tony’s. She’s a handsome, 50-year-old woman who looks nothing like the occupant of a homeless shelter. Her bright red dress and dangling gold earrings stood out in blinding contrast to otherwise drab surroundings. Her manner was anything but that of a drifter.

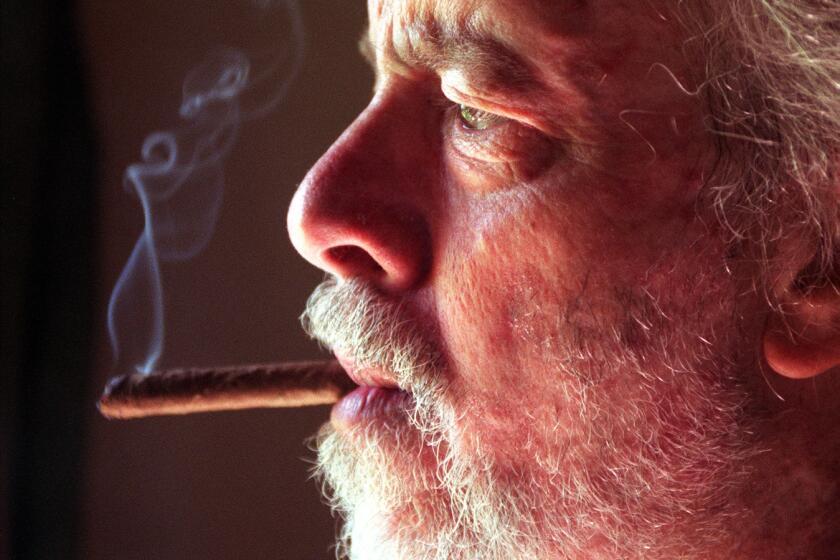

The woman’s name is Josephine. She didn’t want to be identified, but did want to talk about her screenplay, which is about an old guy with dreams of his own who makes them come true.

I was surprised when I read the treatment. I thought it would be her story, the tale of a woman lawyer so torn up and guilt-ridden by the subsequent crimes of the man she saves from prison that she melts into the shadows to hide from her conscience.

But when I asked her about it, she said she didn’t even want to discuss that part of her life. All she was interested in doing was having me help her raise $5,000 to pay a man who was going to produce her movie. He needed it, she said, to hire someone to arrange financing for the film.

I never heard of that before but warned her not to give money to anyone. “The town’s full of barracudas who’ll eat you alive given half a chance,” I said. But I could tell by the look on her face she wasn’t about to listen to me. There is no logic to a dream.

Josephine isn’t stupid. She was raised in a good family, attended private schools and has a master’s degree from a Midwestern university. In the late 1970s, she was the first black person ever appointed to the staff of a state’s legislative leader.

“I had a lot of chances to do a lot of things,” she told me that day at Tony’s. “This is what I want to do. It makes me feel alive.”

*

Ignoring efforts to get her to talk about her last legal case, Josephine said a divorce and the death of her parents finally drove her to asking God what she ought to do. He said she ought to write a screenplay.

You’ve got to listen to God, I guess, so she wrote the script whose treatment I saw, about the old man. Then she came West, to San Francisco first, where she worked at Macy’s and then to L.A., packing her dream.

Jobs aren’t all that easy to come by down here. Josephine ended up serving meals and sweeping floors in an old folks’ home and trying to sell her script. She finally found the producer who wants $5,000, and that’s where she is now.

I’m not sure why she won’t write her own story. I don’t even know if it’s true. Fantasy has a way of emerging as reality in the town where illusion was born. Telly Miller believes her, and I suppose that’s good enough.

At the end of our conversation, Josephine said she’d call me in two weeks, but she never did. Maybe all she ever wanted from me was a way to get to the five grand, but I sure as hell am not into raising money for someone who says he needs it to produce a movie.

If that’s what it takes to buy yourself a tomorrow, hold off, Josephine. I’m sure if you wait long enough the price is bound to come down. Bargains abound in the City of Dreams.

More to Read

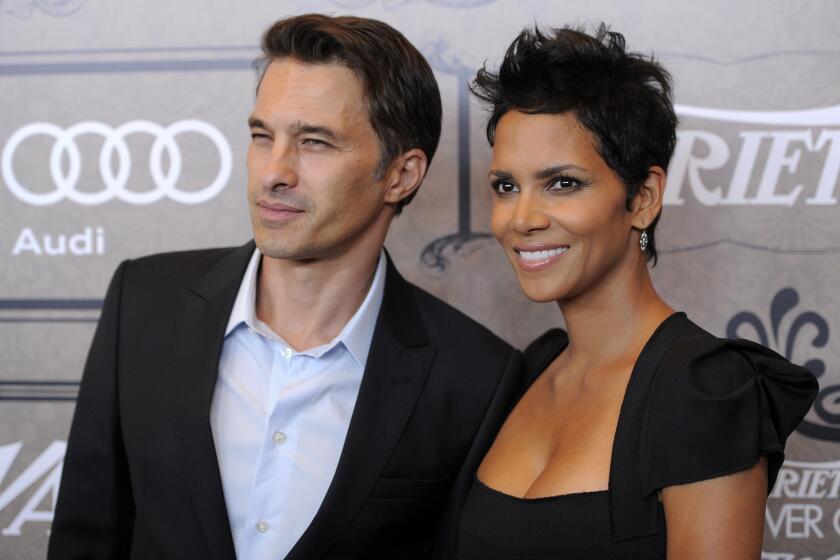

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.