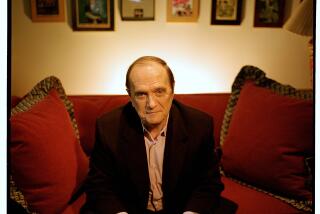

Agent Swifty Lazar, Pioneer Deal-Packager, Dies at 86 : Hollywood: He parlayed boldness into a star-studded client list and hosted legendary Oscar night parties.

Irving Paul (Swifty) Lazar, Hollywood’s best-known literary and talent agent whose tenacious deal-making and star-studded client list made him a pioneer in the packaging of modern motion pictures, died Thursday night.

The agent died at his Beverly Hills home of kidney failure, according to friend and social secretary Teresa Sohn. He was 86.

Dubbed Swifty after he accepted a dare and made five movie deals in one day for his friend Humphrey Bogart, Lazar had since the 1940s commanded record-setting fees for hundreds of writers, producers, directors, choreographers, composers and lyricists around the world.

For more than three decades, Lazar’s famed Oscar night party--held most recently at Wolfgang Puck’s Spago restaurant--had made him a celebrity host as well.

Distinguished by his shiny, bald head and black-rimmed Mr. Magoo glasses, the 5-foot, 2-inch Lazar had a giant reputation as a tough, sometimes brazen negotiator. He liked to say he could assemble the essential elements of a movie from his clientele--all except the actors, whose constant need for reassurance, he said, usually made them too time-consuming to have as clients.

“Packaging is what I do a lot of. Except for the actors,” he told Joseph Heller in 1963, just before he sold the motion picture rights to Heller’s novel “Catch-22.” “I’m what you might call a catalytic agent.”

Indeed, Lazar’s career traced the arc of ascendancy of the agent in America.

“The town will be much poorer without him,” said dancer Gene Kelly, a Lazar friend for 50 years. “A lot of towns, including London, New York and Paris.”

Serving as a liaison between disparate talents and the studios or publishers who sought their help, Lazar was among the first agents to shape entire productions--a job he found satisfying as well as lucrative. When he sold “The Seven Year Itch,” he collected commissions from George Axelrod, the author; Charles Feldman, the producer, and Billy Wilder, the director.

“He made more out of ‘Itch’ than anybody else,” Axelrod told the Saturday Evening Post.

But Lazar’s knack for assembling the creative forces of Hollywood was perhaps best illustrated each Oscar night, when he and his wife, Mary, who died in January, hosted their exclusive, glitzy party.

The black-tie dinner, which lured hundreds of stars and star-seekers from the Motion Picture Academy’s official proceedings, was a magnet for legends and ingenues alike. The party kept the spotlight focused on Lazar long after some of his earliest big name clients, such as Truman Capote, Ira Gershwin, Vladimir Nabokov and Cole Porter, had died.

It was an elaborate production. To ensure that no one had to sit near an ex-husband or ex-scriptwriter, guests nibbled duck sausage pizza and toasted dill brioche in two rooms. To keep from elevating one room or the other to instant A-list status, Lazar had no assigned seat, preferring to roam back and forth between such personalities as Michael Jackson and Paloma Picasso, Elizabeth Taylor and Quincy Jones, Tony Curtis and Jimmy Stewart.

The fete was just one example of how Lazar loved to mix business, socializing with the rich and famous--from Sinatra to Madonna--and never wasting a sales opportunity.

To clinch a deal, he was said to have accosted one studio executive as he dined at Romanoff’s and another as he emerged naked from a steam room. Once, while flying coach class in the 1950s, Lazar spotted Spyros Skouras, the head of 20th Century Fox, sitting beyond the partition in a first-class seat. It was the last time Lazar ever skimped on travel.

“I could have sold Skouras $300,000 worth of stuff,” he grumbled to Time magazine.

Over the years, Lazar’s eccentric behavior became legendary--a process that Lazar, knowing the value of a good story, did not discourage.

The bantam-like agent’s distaste for dirt caused him to wash bars of soap before he used them. A hypochondriac, he had his sheets changed twice a day. When he stayed in hotels, he had a path of towels laid out between the bathroom and the bed--the place where, telephone in hand, he made many of his deals.

It was said that if Lazar was not invited to a party, he would arrange to leave Los Angeles so he could say he had been out of town. According to legend, in order to fall asleep at 2 a.m., the manic Lazar had to begin swallowing sleeping pills at dinner time.

Nearly as often as not, Lazar sold properties that he had not been retained to represent.

“Consent of the author is not necessary for me to work in his behalf,” Lazar told Heller. Later, he told The Times: “The greatest fun is to sell something you don’t represent at all. If I like something I go out and sell it. I usually manage to get paid anyway.”

Lazar saw himself as more than a hired hand. He was a super-agent, a man with vision and with enough well-connected friends to turn vision into moneymaking reality. Lazar thought his friend, novelist Irwin Shaw, had put it best: “Every writer has two agents, his own and Irving Lazar.”

Even Lazar’s birth became fodder for tale-telling. Lazar liked to say he was born in 1907 in stately Stamford, Conn.--he even listed that as his birthplace in “Who’s Who.” But in truth, he was born in a tenement apartment on Manhattan’s lower Eastside.

The oldest of five sons, he grew up in the Brownsville section of Brooklyn where his father, a German immigrant, owned a butter and egg wholesale business. The neighborhood was rough--Lazar said he learned survival skills from sparring with street gangs. From the gangsters, meanwhile, he received his introduction to fashion. Clothes would soon become an obsession.

From age 10, his growing wardrobe consumed much of the money he made washing bottles and doing other odd jobs. He spent the rest at the theater, watching such vaudeville performers as Sophie Tucker, who would later become a client.

Lazar went to Fordham University and then Brooklyn Law School, where one of his professors--recognizing Lazar’s well-honed persuasive talents--hired him to solicit students for a Bar preparation class. Lazar made enough on commissions to finance what would become a lifelong habit: He almost always picked up the check.

Lazar graduated in 1930, worked briefly in a Manhattan law office representing show business clients and became an agent at the Music Corporation of America. The reason, he said, was simple: He preferred an agent’s 10% commission to an attorney’s 1%.

For the next decade, Lazar booked bands and acts in New York and around the country, spending his evenings hopping between nightclubs--a habit that prompted Walter Winchell to call him “the rabbit.”

One day Lazar learned that a nightclub was looking for a Hawaiian bandleader. Lazar, who knew of a Hawaiian who was playing bit parts in radio, told the club owner he had just the man for the job. Forgetting the Hawaiian’s name, Lazar invented one: Johnny Pineapple. For years afterward, David Kaohoni and his band toured under that name.

In 1942, Lazar--who at age 35 was too old to be drafted--enlisted in the Army Air Corps. He was the smallest man in his class--a fact that led Heller, writing about his agent in Show magazine in 1963, to joke that the tiny lieutenant was often marked absent at bed check although present and asleep.

While in the service, Lazar pulled off the deal that would change his career. Assigned to Mitchel Field, Long Island, he heard that the Air Force was going to produce a show that it hoped would rival “This Is the Army.” Lazar immediately fired off a memo to the military brass listing the big names he could attract.

Lazar said he could sign Rodgers and Hammerstein to write the songs, George Kaufman and Moss Hart to write the sketches, and Clark Gable and Jimmy Stewart as headliners--none of whom he had ever met. Given the go-ahead by Gen. Hap Arnold, Lazar approached Hart, who said he would consider the project only if he got an invitation from Arnold himself.

“To my astonishment,” Hart told the Saturday Evening Post years later, “a telegram came.”

Lazar accompanied Hart to Arnold’s office, and when the general demanded to know what was up, Lazar launched into a sales pitch. The resulting show, “Winged Victory,” boasted the talents of Hart, Red Buttons and Mario Lanza and raised more than $5 million for Air Force relief.

When Lazar got out of the service, Hart lured his new friend to Los Angeles and helped induct him into the dizzy world of Hollywood society. He introduced Lazar to lyricist Gershwin and his wife, Leonore, whose house served as a gathering place for many of the city’s creative spirits--Howard Arlen, Judy Garland, Lauren Bacall and Bogart, to name a few.

It was Hart who persuaded Lazar that it was possible to invent himself as a new kind of gentleman agent who moved in the same witty and glamorous circles as his clients. Later, Lazar would acknowledge that Hart created him.

Soon, Hart began peppering his phrases with multi-syllabled words and Briticisms, dropping his Brooklyn accent and adopting Noel Coward’s “dear boy” at the end of his sentences.

It pained Lazar to see himself described as a Hollywood agent, as if affiliation to a single city implied a lack of sophistication.

“I am a literary agent. A national literary agent. . . . You can’t be a Hollywood agent and handle Moss Hart, Teddy White, Arthur Schlesinger, Roald Dahl, Noel Coward, Francoise Sagan, Georges Clouzot,” Lazar once told New York magazine, commanding the magazine’s reporter to “write that this misnomer always annoyed Lazar.”

Lazar won new clients with his reputation and his bravado. Shaw, the writer, said he grew to admire Lazar after the tiny man joined Shaw and several other tall friends in a rough game of riding ocean breakers on a rubber raft. Only later did they discover that Lazar could not swim.

In 1962, at age 55, Lazar--a notorious ladies man whose personal telephone directory was once indexed “Girls--Hollywood,” “Girls--Vegas,” “Girls--New York,” and “Girls--Europe”--got married. His bride was a striking former model in her 30s named Mary Van Nuys, and once they were wed, some said, Lazar’s social cachet only improved.

But as the Hollywood movie moguls with whom he had dickered for years retired and were replaced by what he called “nervous executives,” Lazar shifted at least some of his attention from Southern California.

In the 1970s and 1980s, he added more East Coast writers to his clientele, such as Art Buchwald and Theodore White, and invested in various Broadway shows. For sometimes four months a year, the Lazars would abandon their Beverly Hills home in favor of their Manhattan apartment around the corner from the swank Le Cirque restaurant, where they often entertained.

Lazar was blunt in his criticism of the new generation of studio executives.

“Those whiz kids who come into the business without any frame of reference but television, I don’t understand them,” he told The Times in 1980. “Vulgarity seems to be their answer to everything. . . . These baby moguls are interested in only one thing: making money.”

Lazar and his wife, who opened her own production company around that time, became more involved in movie-making. He was a producer on several projects, including the television adaptation of Colleen McCullough’s romantic novel “The Thorn Birds.” His sale of the television rights to Shaw’s “Rich Man, Poor Man” was said to have spawned the TV miniseries as a form.

But Lazar’s heart--and most of his energy--remained with his literary clients. And he made no apologies for the clients he chose. In the early 1970s, Lazar, a lifelong Democrat, agreed to represent Richard Nixon, promptly selling the former President’s memoirs for a reported $2 million.

Late in Lazar’s life, after many of his friends had died, the agent persisted in traveling and hosting his parties. Axelrod, the writer, told New York magazine that he believed that Lazar was determined to be forever young.

“His theory is that he can’t possibly die if he has tickets to the ballgame,” Axelrod said.

Years before his marriage, Lazar wrote a will that left every cent to the wives of a dozen of his friends.

The will, written in the 1950s, reportedly stated that the 12 women--among them the wives of Axelrod, Bogart, Gershwin, Hart, Shaw and Wilder--were to be entertained at a three-day party at the Beverly Hills Hotel. Lazar was even said to have planned the menu for his wake.

“It ought to be one hell of a do,” he told the Saturday Evening Post. “I wish I could make it myself.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.