Small Business Subsidy in Health Plan Reported

WASHINGTON — Low-wage earners and many of the small businesses that hire them would be able to buy mandatory health insurance with government-subsidized discounts under the Clinton Administration health care reform plan, White House sources said Monday.

In addition, President Clinton’s top health policy analysts are crafting a standard benefits package for the uninsured that will cost about $1,800 per person and $4,200 per family annually--roughly the current national average for health policies, sources said.

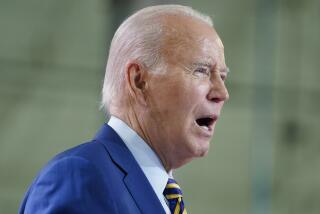

These and other details of the President’s evolving health care initiative are emerging as Clinton returns to Washington from vacation this week and begins to put the finishing touches on a massive reform agenda that he expects to unveil this fall.

Yet even before the President presents his plan to Congress, outside analysts were quick to challenge the calculations underlying the proposed government subsidies and the cost estimates of the standard benefits plan.

The relatively generous subsidies for small businesses and low-wage earners proposed by the reform task force underscore the Administration’s desire to win the support of the nation’s small business owners. So far, small firms are among the harshest critics of Clinton’s plan to require all employers to provide workers with health insurance, with the cost shared by the firms, their employees and, in some cases, the government.

Despite the Administration’s apparent overture, a spokeswoman for the National Federation of Independent Business, which has more than 500,000 members, said that the group remains unalterably opposed to any government mandate to provide coverage.

“The whole concept of a subsidy should tell the White House that the mandate is burdensome,” said Leslie Aubin, a federation health policy analyst.

Administration officials have said that the President intends to require businesses to pay at least 80% of the cost of a standard health plan for its workers, with employees paying the rest. But the emerging Clinton plan would place a maximum ceiling on such outlays: no more than 7.6% of total payroll expenses for large firms, 3.2% of payroll costs for small firms and 1.9% of wages for workers.

The plan to subsidize the cost of coverage for some workers and their employers is consistent with past Administration statements of intent. But until now, no details had been available to indicate which employees and employers would be affected.

Sources familiar with the task force deliberations said that government-financed subsidies would be provided to all firms with fewer than 50 workers, as long as their wages average less than $24,000 a year.

If the standard benefits package costs $1,800 per single employee as currently projected, the employer’s 80% share would amount to $1,440 a year while the employee would be expected to pay the remaining $360, unless the employer chooses to pay more.

The proposed subsidies would reduce that burden, based on a sliding-scale formula keyed to wages. An unmarried small business employee earning $5,000 annually would receive a subsidy of $240, while the employer would get $960, for a total subsidy of $1,200 toward the $1,800 annual premium. That would leave the worker with a tab of $120 and the employer $480.

For a single wage-earner making $10,000 a year, the subsidies would be halved, thus doubling the payments by both the employer and the worker.

For family coverage, again using the standard 80%-20% formula, employers would pay an average of $3,360 a year and their employees $840, based on the projected $4,200 price tag of the government-designed family benefits package.

The figures would be lower for those who qualify for subsidies. A married small business worker earning $10,000 a year would get a $600 subsidy, and his or her employer would get $2,400, for a total subsidy of $3,000. That would leave the worker with a tab of $240 and the employer $960.

A married worker earning $20,000 a year would receive a $360 subsidy, while his or her employer would get $1,440, for a total of $1,800. That would leave the worker with a bill of $480 and the employer $1,920.

A married worker earning $30,000 a year would receive a $120 subsidy under the Administration plan, but the employer would not get a subsidy. That would require the worker to pay $720 in premiums and the employer $3,360.

The subsidies would not be restricted to employees of small businesses, however. All families with annual incomes of no more than $21,514, or 150% of the official poverty level, would receive government assistance, sources said.

In all cases, subsidies would not go directly to individuals or employers; they would be channeled through health insurance purchasing alliances, made up of consumers, that would bargain with medical providers for the best coverage plans.

White House officials stressed that the subsidy and cost figures cannot be considered final, since Clinton has yet to sign off on these and other key elements of the plan.

While the federally defined standard benefits package is intended primarily for the 37 million Americans who currently lack health coverage, its cost and scope will have far-reaching repercussions. Eventually, anyone who opts for a more generous benefits package may have to pay extra for the broader coverage, possibly in the form of taxes on “luxury” benefits. That added burden could be imposed as soon as three years after the reforms are enacted and implemented, White House sources said.

In developing a national benefits package, Administration analysts have used the standard Blue Cross-Blue Shield plan as a model. That plan’s annual premiums are $2,179.84 for an individual, and $4,580.42 for a family, according to a Blue Cross spokeswoman.

But John Erb, a consultant with Foster Higgins, a large health research organization, said a recent survey of 2,400 firms found that average annual premiums for 1992 were $2,814 for individuals and $6,613 for families, noticeably higher than the White House estimates. Erb said that 1993 costs are likely to be at least 10% higher.

Sources said that, under the Administration’s emerging plan, each state would be required to set up at least one large purchasing alliance by Jan. 1, 1996.

The President will propose the creation of a seven-member National Health Board with broad powers to set spending targets and alter the standard health benefits package. At least one seat on the board would be designated for an advocate of state governments, officials said. The proposal is sure to be popular among governors, who have ardently demanded flexibility in implementing national health reform. But it could meet resistance in Congress because all the members would be appointed by the President, even though they would have to be confirmed by the Senate.

All seven board members would serve four-year terms, with the chairman’s term running concurrently with that of the President, for a maximum of three terms; the other board members would serve staggered terms of no more than eight years total.

The potentially powerful board is also likely to have various advisory panels made up of representatives of physicians, hospitals, drug companies and other health care industries, sources said.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.