COVER STORY : The Death of Jaime Casillas : He loved partying, friends, girls. But an old joke went violently wrong when the 20-year-old father greeted a buddy with the signal of a rival gang and was answered with gunfire.

What the . . . you going through my turf throwing the ‘B’?”

It was the last question Jaime Casillas heard before he died.

The “B” was a familiar greeting between Casillas and “Goodtime,” an alleged gang member. Whenever the two friends saw each other, they jokingly exchanged rival hand signals--Goodtime would make the sign for the Florence gang, and Casillas would throw the “B,” a signal for a Huntington Park gang known as the Brats.

The “B” cost 20-year-old Casillas his life. And the gunman who asked the fatal question allegedly was none other than Goodtime.

“It was as if Jaime saw the devil,” said a witness to the shooting, describing Casillas’ reaction to the question and the sight of his pal toting a pistol and an accomplice wielding a shotgun. “You couldn’t believe it. Jaime didn’t even gasp.”

In Los Angeles County last year, a record 801 people died in gang-related violence. Amid such mind-numbing figures, Casillas’ death on Jan. 15 could easily be chalked up as just another statistic.

But it does not lessen the pain that his murder inflicted on his family, friends and neighbors. And it is another chilling reminder of how gangs devalue human life, of young men and women who live in a world where minor disputes--or expressions of displeasure at a joke--are settled with guns.

“I feel that we’re living in another world,” said Casillas’ mother, Maria Luisa, 54. “They don’t have a love of God. I don’t understand how someone in their right mind could cause so much pain and suffering.”

As far as the gang members were concerned, Casillas had defiled what is almost a sacred symbol to them. A gang sign takes on serious meaning for those who wear their symbols in tattoos and mark their territories with graffiti. It is used to flaunt someone’s allegiance or, when flashed to rivals, carries a fierce challenge that can end in death.

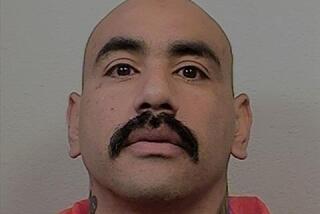

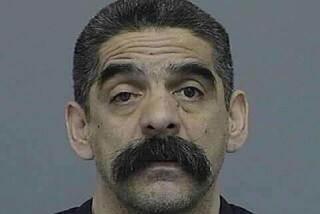

Los Angeles County sheriff’s deputies have identified Goodtime as Ronald Robert Ayala, 19, whom authorities say frequents Huntington Park, Walnut Park and Bell. Ayala and the other gunman, whose identity has not been released by authorities, are being sought.

Witnesses who saw Casillas greet Ayala for the last time at about 11:15 p.m. that Friday said there had been no indication in the previous days that the relationship between the two young men, who had been friends for a little more than a year, had changed. But the speculation in the neighborhood is that Goodtime is a gang wannabe who may have been ordered by members of the Florence gang to kill Casillas as a show of loyalty. Police declined to comment on that scenario.

For Casillas’ parents, his sister and two brothers, the news that Goodtime may have been involved makes his death even more devastating. The notion that he may have been killed by a friend who dined at their table and played with Casillas’ 21-month-old son, Christopher Jaime, is almost unbearable.

Casillas’ mother, other family members said, did not trust many in her son’s wide circle of friends, but she liked Goodtime more than the others. They are shielding her from the fact that he is a suspect in the slaying. They say she may not be able to handle it.

Clutching his high tops, on which Casillas had drawn toes, his sister, Elsa, 27, closes her eyes and shakes her head. Seeing his belongings, his clothes, his messy drawer full of party flyers and girls’ phone numbers is difficult, she said.

“It’s like he’s here, only I can’t touch him or talk to him,” she said. “There’s just this incredible void, you just can’t believe it.”

Jaime Casillas was born Oct. 21, 1972. As a boy, he suffered from asthma and his parents took him to a doctor three or four times a week. That and other ailments probably led to Casillas’ comparatively short stature; he stood only 5-foot-4 as an adult. As he grew older, he increasingly resembled his brother Carlos, 23, but with darker hair and skin.

In fact, Carlos’ driver’s license was among the items Casillas was carrying when he died, along with a tiny picture of his son, a pack of Marlboros and $4.45. He would use his older brother’s ID to get into nightclubs and buy beer.

For the past two years, he belonged to a party crew called The Terribles, a group of about 15 friends who held parties at homes for profit. Now, with so much competition from other crews, they mostly just hang out, frequenting underground nightclubs and parties.

“There was never one boring day with him,” said friend Frank Ibarra, 20. “Now when we go out, it’s all quiet. Before, it would be all rowdy. It’s him. We need him.”

Friends still find it difficult to believe that Casillas isn’t going to show up some day, laughing about what a great joke he has pulled on everyone. They can’t bring themselves to mouth the harsh words that describe his fate. Instead, they say “that day,” or “when it happened.”

“We set aside his beers and we have his chair. We think he’s probably in a better place,” Ibarra said. “Then again, he died knowing who did this to him and that gets us mad.” As was usually the case, that Friday was a night to party. Casillas met up with friends at a bowling alley and left with two friends--Rosie Ochoa, 18, and a 14-year-old girl--to continue the party elsewhere.

They drove to a liquor store to buy beer, and then headed to a spot that Goodtime frequented to see what he was up to. At about 11:15 p.m., Casillas greeted his friend in the usual way.

“Jaime did the ‘B,’ like he always did, and ‘Time raised his hands, like saying, ‘What’s up?’ ” Ochoa said. “I said, ‘Hi.’ ”

Goodtime did not return Casillas’ gesture with his usual sign for the Florence gang, Ochoa said, but he didn’t seem angry either.

Casillas and his two companions left to park at their usual spot on Grand Avenue to drink and listen to music. Ten to 15 minutes later the 14-year-old witness said she saw two men approach some people down the street and heard them ask for Casillas.

She had gotten out of the back seat to stretch her legs and was leaning into the car when she heard the voices. Ochoa was in the driver’s seat of her blue Honda and Casillas was sitting in the front passenger seat.

The 14-year-old turned and one man with a handgun--Goodtime, according to the two witnesses--pointed the gun at her forehead. The other man, who was wielding a shotgun, approached the car from the driver’s side. Ochoa said he put the barrel against her left temple.

Goodtime allegedly turned his gun away from the girl and aimed it at Casillas. They said they saw Goodtime look at his accomplice and shake his head as if to say, “No,” but his partner replied with a firm nod.

“An expression can say everything,” Ochoa said. “We knew ‘Time didn’t want to do it. I swear to God, I thought they were just joking.”

Then, according to the two, Goodtime looked at Casillas and asked, “What the . . . you going through my turf throwing the ‘B’?”

At the same time, Ochoa heard the man on her side of the car prepare to fire the shotgun. She ducked and yelled, “No!”

“I don’t know how I had the strength to duck. I felt the air of the bullet pass on my neck and I turned and saw them kill Jaime,” she said. “I couldn’t believe it, in front of our faces. It’s something you see in the movies. We’ve seen everything.”

Casillas, shot in the face, neck and chest with a handgun and a shotgun, died instantly. Ochoa and the girl said Goodtime threatened to kill them if they talked and the gunmen calmly walked away, turning back to laugh as they did.

Ochoa and her friend say they are taking the death threat seriously and have curtailed their social lives. But they say they are ready to testify if the suspects are caught, and were willing to be quoted for this story because of their affection for Casillas. The younger witness agreed to be quoted, but City Times is withholding her identity because of her age.

“He was one of a kind,” Ochoa said. “I’ll always think of Jaime. I always put him in my prayers.”

After Casillas was shot, the two said they lost control emotionally--slapping, hugging and kissing him, screaming for Jaime to wake up.

They pulled him out of the car and laid him out on a front lawn under a tall banana-leaf tree. The 14-year-old ran toward the Casillas house where Jaime’s father, Pedro, had come out to investigate the shots.

“His dad had a face of pure grief,” she said. Casillas’ mother, according to Ochoa, “came and fainted on top of him, crying to God, saying what did she do wrong to have her baby taken away.”

For Pedro Casillas, 61, an immigrant from Guadalupe Victoria, a small town in the Mexican state of Zacatecas, the end of his son’s life also ended the good memories of the home in which his four children grew up. When they moved there, Jaime was 19 months old, and the children grew up with others their age in the neighborhood. They could play on the street until late at night.

Many of the homes in the middle-class neighborhood near Huntington Park were custom-built. Most have ample front lawns and few windows have bars. Longtime residents say the neighborhood has not experienced much crime and never a murder--until Jan. 15.

Now, friends and family in the neighborhood find themselves looking over their shoulders.

“We can’t go out on the street without thinking, ‘Maybe those persons know us or are going to do something,’ ” said Pedro Casillas.

But his wife, who also grew up in Guadalupe Victoria, said her pain is greater than any of her fears: “There’s just too many memories. I’d like to start somewhere else.”

Their house used to be noisy, with phone calls coming in every few minutes for Jaime. His friend Ibarra says he still dials the Casillas’ number out of habit before he remembers that his friend is no longer there.

Others say Casillas always made friends easily.

“My brother went through every phase there was,” Elsa Casillas said. “He went through a surfer phase, a punk-rocker phase, a skateboarder phase, then he was a cholo , then he went through a rapper phase, then a raver phase with his party crew.”

But as Casillas entered his late teens, there were signs of trouble.

He joined the Brats, but he left the gang after about six or eight months, pressured by his brothers, their friends and his parents to leave behind that lifestyle.

Despite his short stint with the gang, Casillas was tossed out of high school for fights that resulted from the gang affiliation, according to his family. He received his diploma from Huntington Park High School in 1991 after taking night classes.

There were other problems.

At 18, he and his girlfriend, Claudia Ibarra, became parents. Last May, he went to jail for six weeks after pleading guilty to looting beer during the riots. Family members say he had only been along for the ride with Goodtime.

But Casillas was beginning to turn his life around, friends and family said. He worked at odd jobs to help support Christopher, and had signed up for classes at East Los Angeles College. He was to have started school four days after he was killed.

Friends say Casillas always said his son came first, followed closely by his friends and family.

No one could dispute that Casillas loved the company of women. At his wake, at least 10 women approached his brothers, crying, saying they had been dating Jaime. He left a drawer full of girls’ telephone numbers.

“He had a rep,” said Adrian Lopez, 20, a friend who grew up with Casillas. “When he would try to get a girl, she would already know his life.”

Elsa, the oldest of the Casillas children, has taken on the responsibility of holding the family together, making funeral arrangements and staying at her parents’ home even though she has lived on her own for years.

One of the first things she did the night of Casillas’ death was to call Claudia Ibarra, the mother of his son, Christopher, to tell her the news.

“Christopher is the only thing that keeps us from falling totally apart. He makes the days bearable,” Elsa said. “I called Claudia that night and said, ‘Promise me that you’ll never take Christopher away from us.’ He asks for his father and it tears me apart inside. The first few days, I would show him a picture of Jaime and he would kiss him. Now, he pushes it away because he’s mad. He’s mad that he can’t see his father.”

In the days following Casillas’ death, Pedro Casillas and Christopher took a stroll down the street, to the spot where Casillas was killed.

The child threw up his arms and screamed. His grandfather broke down in tears.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.