SURE HE’S SILLY : But Take a Closer Look at Jonathan Richman’s Songs and See If They Don’t Make Good Sense

“I, Jonathan” probably won’t turn up on “Masterpiece Theater” any time soon.

There are some similarities, however, between Jonathan Richman, the auteur of the new album, “I, Jonathan,” and Tiberius Claudius, the Roman emperor whose unlikely career was the subject of the BBC dramatic series, “I, Claudius.”

Claudius, whose ascension to the throne was purely accidental, was scorned by scoffers as a laughable, ineffectual boob.

Richman has his critics, too. They think his low-volume, low-tech music is insignificant and innocuous, soft-headed and childish--especially when he’s being blissfully romantic or irrepressibly silly, which is, one has to admit, often enough.

These critics have never forgiven Richman for abandoning the high-volume, magnum- Angst approach he took in the early ‘70s as leader of the original Modern Lovers. That band’s lone album, “The Modern Lovers,” recorded in 1971-72, is indeed a masterpiece. Just as Rome wasn’t built in a day, neither was alternative rock--and Richman’s earliest album still stands as one of the foundation stones of the modern-rock colossus.

The thing about Claudius in “Masterpiece Theater” was that, given a chance at running the show in Rome, he proved to be an extremely effective, insightful and rather good-hearted emperor. A strong man despite his unimposing looks, he held to solid values in an era of grievous social and moral decay.

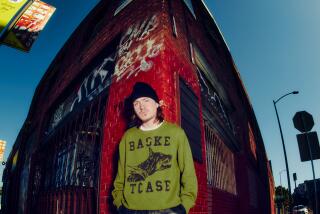

Richman is no empire builder, content as he always has been to put out albums on such small, independent labels as his current company, Rounder, and to play solo shows like the ones tonight and Friday in the cozy confines of Bogart’s Bohemian Cafe. But if you don’t dismiss Richman on the basis of his homely musical means, which include a voice of unsurpassed scratchiness and nasality, a jauntily skittering, non-virtuosic guitar style, and a willingness to play the lighthearted fool, you’ll see that, like Claudius, he turns out to be a fellow of weight and substance.

“I, Jonathan,” like most of Richman’s albums, uses small, sometimes silly-seeming notions to get at questions of fundamental importance, such as what it takes to live a life informed by zest and humor and enjoyment and good sense.

If you’re going to comb highfalutin’ British literary sources for comparisons to this unpretentious rocker, the most apt one isn’t Robert Graves’ “I, Claudius,” the basis for the “Masterpiece Theater” series, but Laurence Sterne’s “A Sentimental Journey.” That charming, 18th-Century novella is about an English parson named Yorick, who sheds his own country’s stuffy formality during travels in France. Yorick’s journey teaches him to greet each new situation with enthusiasm, good humor, an appreciation for the unexpected, and a spontaneous, unstinting display of feeling.

“I, Jonathan” is Richman’s account of his own sentimental journey, compiling song-snapshots of feeling-filled moments he’s experienced. One song recalls how it was to be young and carefree and living in a shack on Venice Beach. Another is an innocent, open-hearted, but also perceptive appreciation of his early musical inspiration, the Velvet Underground (in yet another similarity to Claudius, Richman stutters a bit as he mimics Lou Reed singing “Sister Ray”).

“I Was Dancing in the Lesbian Bar” is quintessential Richman. Its story line is spare indeed: Richman goes dancing in one bar with his friends, finds the vibe too stiff and adjourns to a place where the atmosphere is more conducive to dancing, which happens to be “the Lesbian bar.” The song makes no mention of sexual politics; it has no larger point to draw. Its main reason for existence seems to be its jangly-funk groove, which sounds like a drastically stripped-down, sound-dampened version of Talking Heads or the Tom Tom Club.

At first, it seems that Richman has indeed gone soft-headed--unwilling, or unable, to draw some broader, socially conscious conclusion about his gay-bar experience. Then you realize that the point is precisely that: If you look to generalize your experiences, to use them as fodder for polemics and theorizing, then you miss the enlivening capacity to just have fun and enjoy a good moment.

“I, Jonathan” also includes a luminous song called “Twilight in Boston.” It’s the latest in a series of winsome odes he has written about the city where he was born 41 years ago; by now, you’d think, they’d have put up a Jonathan Richman statue in the Fenway, which has been his favorite Boston haunt to rhapsodize. Nowadays, however, Richman lives with his wife and children in a hamlet in the Sierra Nevada of California.

Richman’s body of work is easily among the sweetest in rock, sometimes to the point of coming off as merely cute. However, for all his sweetness and enthusiasm, he never has excluded the sour, or denied that life can be painful and hard.

One example is “Parties in the U.S.A.,” which shows that Richman can generalize from his own experience to comment on broader issues. The song’s main story line depicts those original Blue Meanies, the Huntington Beach police, summarily shutting down a well-behaved soiree of friends gathered for music and talk. But Richman widens his scope. He wonders, plaintively, what will become of us as a community if we safeguard the right to quiet of the solitary, ain’t-botherin’-nobody television addict, while stifling the gregarious spirit that could strengthen our weakening social fabric.

So people are stayin’ home now and not havin’ fun,

A cold, cold era has begun.

Well, things were bad before, there was lots of loneliness,

But in 1965 things were not like this--

When we had “Hang on Sloopy, Sloopy hang on.”

Maybe the cops kept the quiet that night in Huntington Beach, but they didn’t keep the peace. True peace is the product of people who have found a way to get along, together, in a way that binds and enriches lives. One good example is a typical concert by him, Jonathan.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.